While performing in 1995, Aviv Geffen saw his country’s prime minister gunned down yards from where he stood. The experience only made the Israeli artist’s political resolve stronger, he told Prog in 2011, when he and Steven Wilson launched third Blackfield album Welcome To My DNA.

“There are people in Israel who hate me. Really hate me. For them I present the Devil himself.” From most musicians, this is the kind of self-mythologising aggrandisement you'd take with a whole sack of Saxa. But Aviv Geffen – one half of Blackfield, a fruitful collaboration with Porcupine Tree’s Steven Wilson – is no ordinary musician, and when he casually discusses the animosity towards him from many of his countrymen, you'd better believe it’s true.

He’s Israel’s biggest rock star, but his vigorous campaigning for peace, his outspoken criticism of the government’s occupation of Palestine, his involvement in speaking out for the rights of women and homosexuals and his flamboyant stage presence have stirred the nation’s youth into positive action while rubbing up the country’s leaders and their supporters the wrong way.

He is, in the most literal sense possible, a revolutionary. “I ask my audience to start to ask questions,” he explains. “Why can we invade Jerusalem and the Arabs? Why do we need to control the area? Which is a big, big thing here. I don't think we should go into Jerusalem and think we are in charge of someone’s life. I am speaking against occupation. I’m wearing the make-up to represent the anti-macho. It has become a uniform for me now. And it goes into Blackfield, and everything.”

Geffen's relationship with Wilson stretches back to the mid-90s, when he first heard a Porcupine Tree record. Instantly smitten with their meticulous prog rock, he took it upon himself to make sure other like-minded music lovers in Tel Aviv could get to experience the band live.

“I thought I had discovered the new Pink Floyd!” he laughs. “I wrote to Steven that I loved his album. We had a meeting in Camden in London and I said that I wanted them to come to Israel to play a show. No one in Israel wanted to invest the money to bring them over here, so I got it together myself and brought them over to do their first show here. That’s how we met, and then we had Blackfield.”

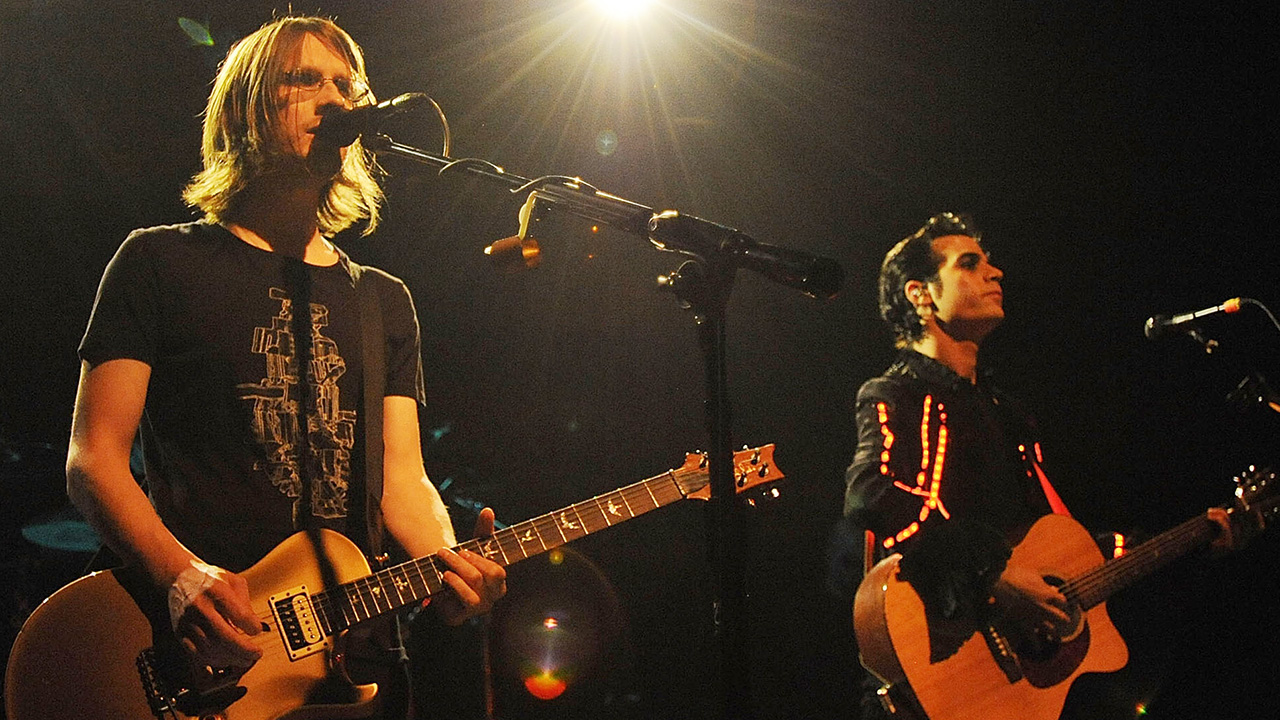

The pair are about to release their third album, Welcome To My DNA, a beautifully mournful record with shades of Pink Floyd and packed with lush strings, elegant melodies and warm, melancholy vocals. Geffen wrote most of the record (Wilson was working on his own solo album at the time), but the pair worked closely together to recorcland produce it.

“Blackfield is not a side project,” says Geffen. “We put everything into it; we work so hard. I think you can hear my and Steven’s heart on each album, and this is the best album we’ve done. We called the album Welcome To My DNA because I was growing up in Tel Aviv, and Steven comes from Hemel Hempstead, but we’re like the same souls. There’s a similar sadness and desperation inside our DNA.

“I can go into my life here in Israel, to go to politics and protest against the government, and he’s a prog rock fan in the UK, but in a way we’re looking at the same thing, which is sadness and being alone.”

It’s the differences in their backgrounds that ignites the creative spark. While Wilson spent his formative years obsessing over Dark Side Of The Moon and learning to create new guitar sounds from his suburban bedroom, Geffen was getting to grips with the unrest in his country.

It came to a head on November 4, 1995. The singer was performing at a rally in Tel Aviv's Israel Kings Square, watched by the country’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. As he left the stage he heard shots fired and saw the politician slump to the ground, instantly killed by an assassin. Geffen was the last person to hug him before his death.

So it’s little surprise that the passionately anti-Zionist star stepped up his efforts to bring about change in the region. It’s a fire that he brings to his work with Blackfield. “I’m more of a reamer and a rebel,” he says. “For all those years I was protesting against the government and against the occupation. I was with Rabin when he was killed – they shot him in front of my eyes.

“And Steven likes his quiet life really. He’s not like a rock star. When I play live with Blackfield I want to give the audience more than a great show. Steven is more quiet, more down to earth, more artistic in a way.”

I was the first one here who was wearing mascara onstage. In Israel it was all new – what you got in England back in the 70s wasn’t here in Israel at all

The murder of Rabin clearly still haunts Geffen. “I think it was the lowest point of Israeli life,” he says. “I’ve become more angry and I have become extremely left wing because of it. It became my life to change Israel, to change my crowd, to change the lives of the people in Israel. These days i’m kind of like a plane that crashed, there are some stages – for example, Independence Day in Israel – people would not allow me to play. It’s fine because it’s my art. In that way it’s really different from Steven; he’s never really dealt with this kind of thing.”

Geffen’s militancy is something he was born with. Various members of his family had an enormous impact on him as a child, some good, some bad. His father, Yonatan Geffen, is an equally outspoken and controversial poet who instilled a love and respect for the power of words. “When I was really young I found that paper can be more deadly than any tank or aeroplane,” he explains.

“Before I started making records back in 1991, no one else was daring to judge the army or the government. Especially me: I’m the nephew of Moshe Dayan, the security minister who actually occupied Jerusalem. I was the first one here who was wearing mascara onstage. In Israel it was all new – what you got in England back in the 70s wasn’t here in Israel at all.”

Ah yes, Uncle Moshe Dayan: the military leader instantly recognisable by his eyepatch, having lost an eye in battle. For all the positive things he learned about life from his father, it’s his uncle who showed him the brutal side of existence. “To me he was really nice – but you should know that he was a symbol of the machismo of Israel,” he remembers. “Everyone wanted to be like him, and I really came and broke the chain. I just broke the chain really hard.”

Bob Dylan and John Lennon, for me, are the most important people as lyricists because they really changed the world

Not many Israeli artists break through in the US and the UK, but Aviv Geffen made the Radio 2 playlist with his single It’s Alright, helmed by super producer Trevor Horn (“an absolute genius”) and he counts Michael Stipe, Bono, Placebo, Suede and Brian Eno among his friends and fans.

“I think that I’ve got an unusual story,” he says to explain his international appeal. “I think my background is so unusual. You see people on the cover of music magazines and they call themselves rebels or those big empty words. I think I’m more of a rebel, and I’m really the punk guy because I really put my life at risk.

“I’m really fighting for what I believe – it’s not just a nice four chords at Glastonbury festival. I think the memories and why I continue to question the order and the running of Israel and the world is important.”

But can musicians still make a genuine difference? Does Geffen honestly think he can peacefully change the world? “Of course,” he says quickly. “Bob Dylan and John Lennon, for me, are the most important people as lyricists because they really changed the world. My life changed because of Pink Floyd and Bob Dylan.

“I think music can change things. I think a lot of the success of Blackfield is because of my story. There are people all over the world who know there’s someone called Aviv Geffen who’s standing up to the Israeli army against all those odds.”

I think we both did a great job… It’s the kind of album you want to hug and put on repeat

At the forefront of his mind today, however, is Blackfield. With months of touring ahead of them, Geffen and Wilson are turning their back on their other musical endeavours for the time being to concentrate on a genuine labour of love.

“Blackfield is really not about the radio and charts," he muses. “I just came from a long summer in which I’d played with U2 and Placebo, and everything was so commercial. Blackfield is like this pure thing to do whatever I want to. I worked on the songs for this album and my mind really wasn’t on the radio. It was on going to the studio and diving to the deepest part of my soul.”

There’s an increasingly large pool of fans getting excited about Backfield’s return, and their star seems to be in the ascent as the venues get bigger. “There are some Blackfield songs that feel like some of the lyrics are too heavy for the radio,” he says. “I think that could be the secret – because we come in from really strong careers, when we go to the studio it’s really about art. Steven really cares about art. He doesn't care about money. That’s why it works so well.

“If you asked me when I started Blackfield, ‘Will you play the Shepherd’s Bush Empire in April?’ I would have said no. But now we’re getting there naturally – it’s building up nicely now.

“Now is the time that we deserve to break through,” he continues, as confident in this new album as he is in every other aspect of his life. “I think we both did a great job, and we worked really hard and achieved many things we could only imagine.

“I’m sure someone in, say, Oxford or Liverpool will get their hands on the new album, and I can’t see any reason they wouldn’t like it. It’s the kind of album you want to hug and put on repeat. I think the album shows how everyone feels fucked up on the inside.”