Note: this interview was conducted in April 2024, before it was announced that Heart's Royal Flush tour would be postponed to allow Ann Wilson to recover from a course of preventive chemotherapy.

Fittingly for two self-possessed opposites, Ann and Nancy Wilson have settled about as far away from each other as is possible within the United States land mass: Ann on a fingertip of the eastern seaboard, Nancy nearly 3,000 miles to the west as the crow flies.

This week in early spring, both are at their respective homes. Ann in Florida, Nancy in the verdant wine country of northern California. Ann, reading glasses perched on her nose, throaty laugh, dressed in black. Nancy, pink streaks in her hair, her black-andwhite collie dog skittering about the kitchen, is more of a chatterbox than her elder sibling, just as quick to laugh. Both are good, easy-going interviewees.

They’re preparing to once more ramp up Heart, the band they’ve piloted for 50 years. And what a journey it’s been. Heady heights, plunging lows. So many indelible songs, such personal drama. Altogether, a rock’n’roll saga of epic proportions. Days from now they’ll be standing on the roof of a downtown Manhattan edifice, the Rockefeller Center, blazing through Bonnie Tyler’s Total Eclipse Of The Heart for an edition of The Tonight Show going out on the night of an actual eclipse. Then there’s the small matter of a world tour planned to stretch for 18 months. It could be their valedictory lap, given that Ann will be 74 this June and Nancy turned 70 in March.

Ann was born in San Diego, Nancy in San Francisco. Their father, John Wilson, was a major in the US marines corps, mother Lois ran the household. The couple had a third daughter, Lynne, four years Ann’s senior. The family moved around with John Wilson’s postings, stations in Panama and Taiwan included. When he left the service, disillusioned with the war in Vietnam, they settled in a suburb of Seattle, Bellevue, where the sisters passed through the same school, Sammamish High. Ann graduated in 1968 and went off to art college with aspirations of becoming a fashion designer. Nancy left in 1972 and went to Portland State University to major in literature and creative writing.

Throughout, the two made music together: Ann the singer, Nancy accompanying on acoustic guitar, piano and vocal harmonies. With two friends they had a four-part harmony group, The Viewpoints. While at university, Nancy performed solo acoustic sets in coffee shops and cafes. Ann joined a rock band, Hocus Pocus, alongside guitarist Roger Fisher and bassist Steve Fossen. Fisher had an elder brother, Mike, who was evading the Vietnam draft up in Vancouver, Canada.

One night, Mike Fisher snuck over the border to see Hocus Pocus play a bar called the Iron Bull in the frontier town of Bellingham. He was bowled over by Ann Wilson, and she with him – love at first sight. She followed him back to Vancouver. Subsequently, Roger Fisher, Fossen and latterly Nancy beat the same path, and by the beginning of 1974 Heart were born. By then Nancy was also in a relationship with Roger Fisher. The two sisters and the two brothers intertwined in perfect harmony. For a while, anyway.

What is your recollection of first hearing music?

Ann: Being in the car with my dad, on the way to the hospital to see new-born Nancy. Sixteen Tons by Jimmy Dean came on the radio. I’ll never forget hearing that song.

Nancy: I can remember looking through the bars of my crib and my mum singing a lullaby to me, Curly Headed Baby. Her voice had a round, smoky quality, kind of like Patti Page. We always had a stereo system with good speakers in the house, and a collection of vinyl. Records would always be spinning, everything from classical to Broadway musicals. James Brown and Aretha Franklin. Barbra Streisand and Ray Charles. Ann and I would do interpretive dances to scenes from West Side Story in the living room, jumping off the back of the couch.

Who or what inspired you to start making music?

Ann: It wasn’t until high school I realised I could sing and carry a tune. I didn’t ever sing solo until much later. Our father especially was really behind us when we got started with music. Mother was a little more sceptical. Two out of three daughters going into the entertainment business wasn’t exactly her idea of a safe pastime for young girls. She just wanted us to be happy, basically. Time and again she said to us: “I’m not going to tell you what to do or be necessarily, but be blissful and do what you really love.” We did.

Nancy: Our parents saw how consumed we were, so they were very encouraging. It was the neighbours, the Joneses, that said: “‘Don’t let Nancy play guitar, it’ll ruin her fingernails.” Well, they were right, but I didn’t really care about fingernails. Our parents cheered us on. They helped us make payments on cheap guitars. Ann had the voice of doom. I was really consumed with being her accompanist. There really weren’t any women to inspire me. I was inspired by Jimmy Page, Stephen Stills, Neil Young, Paul McCartney and John Lennon, Elton John’s piano playing. They were my muses.

Ann: They were all men back then. There were a few female singers I really loved, like Judy Garland, but in those days there wasn’t yet a female rock’n’roll icon. My inspirations were Robert Plant, Lennon and McCartney, Rod Stewart, Elton John, Harry Belafonte.

When did you begin performing in earnest?

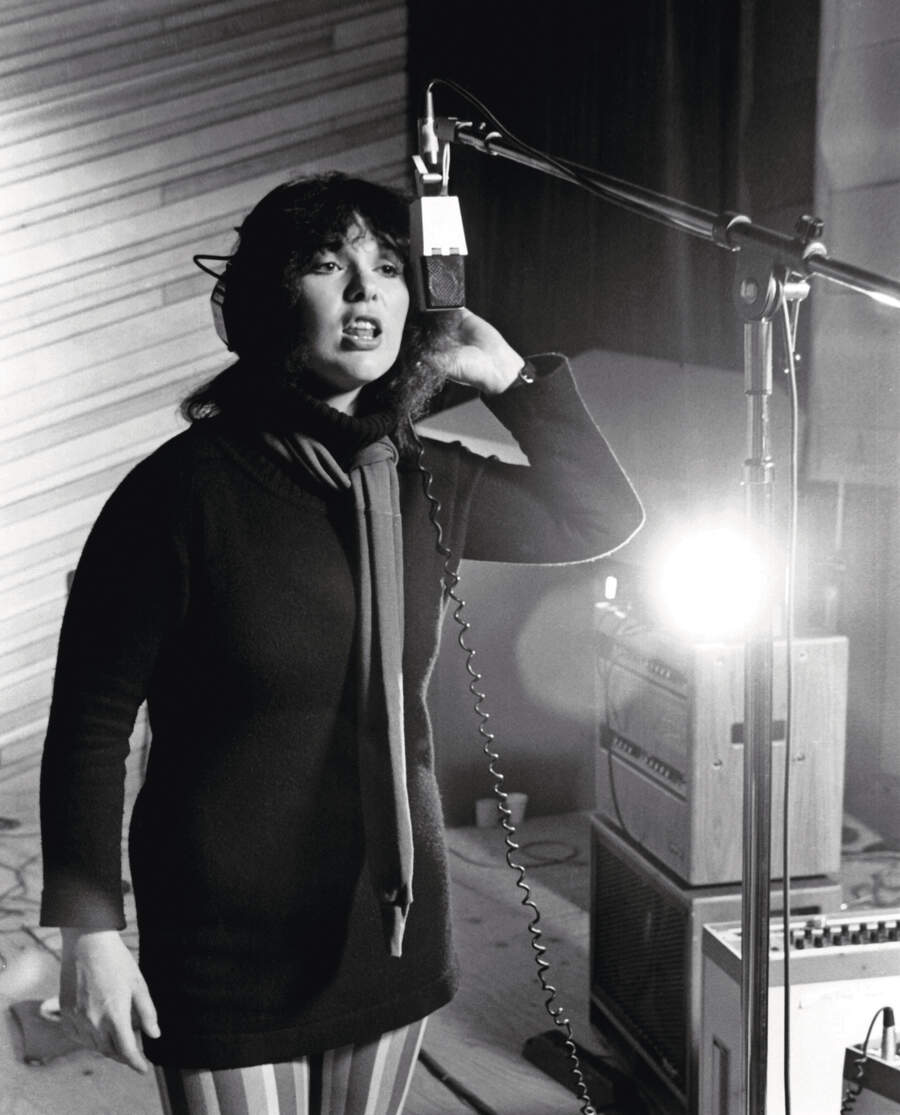

Ann: I answered a newspaper ad and auditioned for these guys Roger Fisher and Steve Fossen. We drank coffee all afternoon and jammed, and they hired me. I was really lucky because I wasn’t perfected as a singer at all. I was just somebody who loved to sing. I was going to Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle. I found out really quickly, in the first year, I wasn’t meant to be a fine-artist. I was splitting my time between the band and school, and I’d be up all hours of the night playing with the band and then having to make an eight a.m. class. I couldn’t do it. I had to choose one, so I chose the band.

Nancy: I’d walk to the Pepper Grinder bar with my acoustic guitar, a block down from the Pacific University campus in the tiny town of Forest Grove, Oregon. They had a PA and a mic. I played Locomotive Breath by Jethro Tull and stuff that was on the radio at the time. I once got twenty dollars for playing Stairway To Heaven all by myself. I had to buy my albums somehow, right? I tried to slip in a few original things too. I was working on music of my own. Soul Of The Sea was one of the songs I was writing at the time that ended up on the first Heart album. I was always trying to write with Ann long-distance. We’d have phone calls, and make cassette tapes to mail each other.

Eventually you joined up with each other again in Vancouver.

Ann: I went up there in 1971. I was following my heart. I fell in love. Michael had a little cottage in the woods, overlooking a creek. That was where we settled. We lived there for a good six months before the rest of the band followed me and wrecked our solitude. I wasn’t pleased about it. Not at first. It wasn’t my idea. I wanted the romance of just being with him in this little round house to go on for ever. Then in early 1974 Nancy joined us. She’d been coming up and sitting in with us before then, but she was serious about being in college. She was an intellectual in that regard.

Nancy: I dropped out of college. My parents were trying to pay for it, but it was really hard for them. We learned how to play on a big stage at a Vancouver club called Oil Can Harry’s. A lot happened really quickly.

Ann: I’d been in bands without Nancy for a long time, so it was just different. Nancy’s a great harmony singer, and acoustic guitar player. She added to Heart what I felt it was missing – an acoustic heart. That was something Zeppelin had, and I always really valued. It made Heart vastly more interesting for me.

Was Heart effectively the Wilson sisters’ band all along?

Ann: No. I have to take issue with the fact it’s me and Nancy’s band at all. The people that are in Heart are always treated on an equal footing. We don’t hire back-up musicians and throw them some cash.

Nancy: Ann and I have always been the left and right hand of the same musical being. We couldn’t be more different as people. She’s like our dad, and I’m more like our mum. She’s way more of a soldier, a warrior. We’ve always been like the eye of the hurricane with Heart. We’ve always been able to figure out how to communicate our roles as the two main leaders. Both of us together own it fifty-fifty, so we can’t out-vote each other.

With Mike Fisher acting as their de-facto manager, the fledgling Heart hooked up with producer Mike Flicker, transplanted to Vancouver from LA. They began recording demos for their debut album at local indie label Mushroom Records’ Can-Base Studios. Flicker, who had initially been more interested in nurturing a solo Ann Wilson, also brought two of his favoured session musicians into the line-up: keyboard player/guitarist Howard Leese and drummer Michael Derosier.

At the basest level, the completed album, Dreamboat Annie, sounded like Led Zeppelin in touch with their feminine side. Powerful and whimsical by turns on two standout Wilson sisters’ songs, Magic Man, Ann’s hymn to Mike Fisher, and Crazy On You.

Released through Mushroom in September 1975, the album got off to a slow start, inching to 30,000 sales in Canada. A slot opening an arena show for Rod Stewart in Montreal and radio airplay over the border in the US gave it wings, and by the following year Dreamboat Annie had gone platinum. Without consulting his charges, Mushroom boss Shelly Siegel promoted it with an infamous full-page ad in Rolling Stone magazine: the album’s cover artwork, the Wilsons photographed back-to-back and bare shouldered, beneath the suggestive headline: ‘It Was Only Our First Time’. It was enough, along with a lack of tour support, to prompt Heart to flee to major label CBS’s new Portrait imprint.

Siegel hit back in April 1977, releasing the unfinished second album Heart had been recording for him as Magazine, a month ahead of their official debut for Portrait, Little Queen. Both records went platinum. Little Queen, produced once again by Mike Flicker, delivered another signature track, the piledriving Barracuda, Ann’s response to a salacious record company minion asking after her lover and meaning Nancy. The following year’s Dog And Butterfly raced to two million sales in the US. Its centrepiece, the Zep-heavy anthem Mistral Wind, is both sisters’ favourite Heart song.

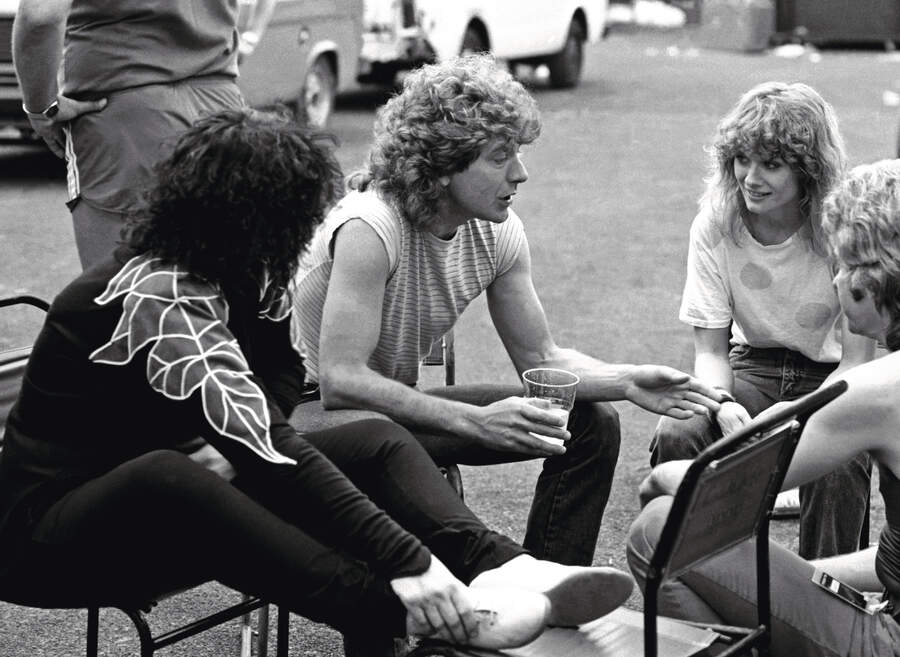

Nothing could go wrong for Heart, it seemed. Until it did. Touring Dog And Butterfly, Roger Fisher’s infidelities ended his and Nancy’s relationship. Ann and Mike Fisher broke up at the same time. Further muddying the waters, Nancy took up with Michael Derosier. The band limped through to the end of the tour, after which the Wilsons fired the Fishers.

What stands out for you now about the making of Dreamboat Annie?

Ann: I knew absolutely nothing about singing in the studio on a big mic. It was going from zero to ten. Mike Flicker was my mentor. He taught me everything I know in those early recording sessions. Making a record is nerve-racking. You’re under the microscope as a singer. I thought I sounded high and shrill.

Nancy: It was so intimidating to go into an actual studio. To me it seemed huge. Years later we revisited Can-Base for a radio broadcast, and it was tiny. We were so doggedly determined to be good. I think we actually pulled it off.

How challenging was it to assert yourselves as artists and be two women in a rock band at that point in time?

Ann: It was 1975. Women were thought of as sex objects, that’s all. Mushroom Records decided they were going to capitalise. Two chicks and two sisters – wow! Think of the possibilities for titillation. All of that made us really angry. When we saw ourselves being treated in such a sleazy, cheesy way we totally rebelled.

Nancy: There’s a little more guardrail now for the chauvinism that was so rampant at the time. I think we took it with a ton of salt – like, over the shoulder. Boys will be boys, men will be slimeballs. If you’re a pretty girl, you have to endure it. But you’re really there to do the work and prove to everybody that you’re good. Being good had everything to do with it.

When a band lifts off, what’s it like being at the centre of it?

Ann: Very exciting. It seems like the good news keeps on pouring in. Pretty soon you’ve got money pouring in too, and everybody’s buying sports cars and fur coats – at least in those days – and houses and gifts for their parents. In the early days, Michael and I bought a house and a Jaguar XKE. Those were our big ‘beautiful people’ expenses.

You must have had a particular nagging doubt, though – two sisters dating two brothers in and around the same band. It was bound to go wrong, wasn’t it?

Ann: Oh yes, there was constant doubt. Whenever you’re in a relationship with someone, the greeneyed monster is always right around the corner. You’re watching to make sure he’s not looking at anybody else. Being jumpy about it. They jokingly called the four of us the Wilshers. It worked for a good while. It was family. But the typical things started to eat away at the perfection of it all. People find fidelity extremely difficult. That was the undoing of the Wilsher tribe.

Nancy: In my mind it was more of a professional arrangement than a real relationship. It was easier to have someone to bunk with in a hotel than pay for an extra room. There was a communication line between the two brothers and two sisters. Those guys had started the band, and I was new to it, and Roger had a crush on me. I kind of went along with it for a while there. But still, bad idea.

Ann: We didn’t have the stamina that, say, Fleetwood Mac had. It was extremely hard for us to work together as musicians. The emotional toll it all took. At that point we just needed a breather. Everything was so huge. The money, the fame, interviews. It kind of ate us.

Heart plateaued with 1980’s Bebe Le Strange, their first post-Fishers album and their last with Mike Flicker. Then they hit the skids. Flicker’s intended replacement as producer, Jimmy Iovine, fresh from working on a run of stellar albums for Tom Petty, Stevie Nicks and Dire Straits, bailed from Heart’s 1982 album Private Audition, citing a lack of hit songs. The album sold much less than its predecessors, but better than 1983’s unloved follow-up Passionworks.

In the interim between those two records, Fossen and Derosier were given their marching orders, and Mark Andes (Spirit, Firefall) and Denny Carmassi (Montrose, Gamma) respectively filled their slots.

After Passionworks, Heart left Portrait for Capitol Records. Their new label teamed them with a new producer, Ron Nevison. Outside writers such as Jim Vallance (What About Love), Holly Knight (Never) and Elton John’s lyricist Bernie Taupin (These Dreams) were brought in, and the band’s image was revamped to fit the big-haired/ leather-and-lace-clad template of the era.

At a stroke, Heart were resurrected. Their self-titled comeback album of 1985 went to No.1 in the US, and sold more than five million copies. The accompanying videos – Ann shot in soft focus, Nancy recast as a sex kitten – were hardly any more subtle than Mushroom’s playbook had been, but got saturation coverage on the booming MTV. Bad Animals (1987), which included the No.1 uber-power ballad Alone, and 1990’s Brigade, maintained the band’s upward curve.

How personally did you deal with the slump?

Ann: I partied. I bought a house in Seattle, for me and my friends, and went home. We lived a high life for a couple of years. It was a lot of fun. But it was not necessarily that successful creatively.

Nancy: When we got to Passionworks, we worked with a producer [Keith Olsen] who was hitting bottom on his cocaine habit. Everything was really hard and difficult. We were trying not to get sucked into the cocaine of it all. The album came out, nothing happened. It was nowhere to be found. That was really hurtful.

Me and Ann and our bestie Sue Ennis, who we always wrote with, got together to have a movie night. We watched Terms Of Endearment, then Spielberg’s The Color Purple, and Steel Magnolias. It was a three-pronged cry-fest. We got out a big box of Kleenex and sat around Ann’s library crying for six hours. It actually felt better after we did it. We had some wine and a nice night afterwards.

Ann: In 1983 we met this guy, Don Grierson, who was the head of A&R at Capitol. He believed that with the right songs Heart could be reanimated and brought back. He said to us: “If you give me the opportunity to go fishing for some songs for you, and you write songs too, I bet you we could have a hit record.” And he was right.

How willing were you to be made over?

Nancy: We were a little desperate after the big turkey of Passionworks. We had to do something. It was a new era. The fashion was changing. MTV was pushing the agenda on rock bands to have big hair and ‘the look’. The mind-expansion of the sixties and seventies was turning into the ego-expanded, cocaine-driven 1980s. We were not sophisticated. We were not LA people. It was not a fit, but we did okay. We got through it.

I always had a joke with myself that I’d know I’d made it when I heard a Heart song in an elevator. And it happened; I heard These Dreams in the grocery store. You feel worthy. Like you’ve worked really hard to do something that connected to people.

Ann: The first, self-titled album was fun. The big hair and the wild clothes. It was theatre. Having wanted myself to be a fashion designer, to have stylists heaping clothes on me was great. I loved it. By Bad Animals we were getting tired of it because we were touring so extensively. When you try taking these incredible costumes out into the sweaty country, where it’s a hundred degrees, and you’re dancing around in stiletto heels… So by Brigade we were over it.

Marty Callner, director of your Never promo, once claimed: “Everybody told me how much they loved Nancy’s tits in that video.” How did you square being so objectified on MTV?

Nancy: Yeah, I was kind of the Farrah Fawcett of rock for a minute there. I didn’t feel like that was who I am. I’m a musician first, and I’ve got more to offer than some saucy-looking image of me. But I figured, okay, this is survival, and I’ll be a poster girl for this if I get to go out and play my guitar. It got a little out of hand a couple of times, but who cares? I was indelibly emblazoned in the minds of many men, so I’m glad for that. I can’t complain.

Ann: Everybody in those MTV years was objectified to death. You were expected to look like a model and be a dancer and an actor and sing. Wow. To be a quadruple threat when you’re just a person from Seattle who played in bar bands. It was really hard. I thought These Dreams was a remarkable song. I think Alone also was pretty stunning. But there was something at the very soul of the music we were doing that really wasn’t much like Heart. It wasn’t our words we were singing, it was somebody else’s.

The music business of the 80s is typically perceived as being brash, excessive and OTT. Was it that in your experience?

Ann: Oh, it was definitely excessive. Everything it’s made out to be, it was. There was never enough of anything, including money. It was a very materialistic time. The dignity of women was at a low ebb. But I totally enjoyed being up on the big stages and flying around in private planes, and being entertained in these lavish ways.

On the other side of the 80s, the Wilsons returned to earth. They formed an acoustic covers band, The Lovemongers, and made a partial return to Heart’s roots for 1993’s Desire Walks On. In 1995, Nancy broke off to start a family with her husband, film director Cameron Crowe. The couple had twin boys, Curtis and Billy, in 2000. Nancy wrote scores for Crowe’s films Almost Famous in 2000 and 2001’s Vanilla Sky. The couple divorced in 2010. Nancy married TV music producer Geoff Bywater in 2012. Ann made a covers album, Hope And Glory, in 2007, got sober in 2009, and married Dean Wetter in 2015.

Ever since, with Heart they’ve taken a scenic route, not without its bumps in the road and pitfalls. There have been four well-regarded albums, from 2004’s Jupiter’s Darling to 2016’s Beautiful Broken (that had James Hetfield duetting on the title track), each harking back to the electric-acoustic foundations of their 70s records.

In 2013 the original line-up was inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame by Chris Cornell. Their performance at the ceremony was the first time in 34 years that the Wilsons had shared a stage with Roger Fisher, Fossen, Leese and Derosier. The sisters had made a bigger impression in December 2012, when, with Jason Bonham on drums, they delivered an overwhelming reading of Stairway To Heaven at Led Zeppelin’s Kennedy Center Honors bash, attended by Jimmy Page, John Paul Jones, Robert Plant and US president Barack Obama.

There have been other, tumultuous passages. On August 27, 2016, Dean Wetter was arrested and plead guilty to assaulting Nancy’s teenage sons. Wetter’s ire was raised by the boys neglecting to lock up his RV after a Heart show. Unsurprisingly, the sisters were estranged for two years afterwards. They reunited under the Heart banner to tour in 2019.

Apart for four more years, Ann fronted her own band, Tripsitter, and Nancy went out with Nancy Wilson’s Heart, in which Ann’s parts were sung by Kimberly Nichole, a finalist on The Voice. This latest revival was heralded with a show in Seattle on New Year’s Eve 2023, with Tripsitter serving as the Wilsons’ backing band. Three weeks on from it, they announced Heart’s Royal Flush tour.

How did you navigate yourself out of the 80s?

Nancy: I left the band to try to start a family, and it took a couple of years longer than I wanted it to. My kids were two at the time I rejoined the band. I took them out on tour with me. We had diaper pails in the bus and a nanny along. Every zoo in every large city we played, they went to.

Ann: You mean not falling victim to the emotional carnage? Well, I have a natural ability. These little red flags wave in my brain when I get to a certain point. Like with anxiety, or depression. At a point in the 90s, I realised that I needed something, so I started studying meditation. I learned basic meditation techniques. I can do myself tremendous good by knowing how to stop and be still and be mindful. It’s really saved me a lot of times.

How have you maintained your relationship as sisters?

Nancy: There’s been some challenges, but not hardly around that. It’s been everything else around us. The politics and the family drama that ensues around the peaceful core. You have to expect that. It’s like the movie Twister. You’re caught up in the tornado, and you see the cow fly by, and there goes the tractor. This is my favourite new analogy. You’ve got to hold on tight to something that’s not going to get sucked into the stratosphere. Ann and I know how to hold to the centre. That’s what we do.

Ann: With a sibling, you can get into the habit of assuming you know everything that’s going on in their head. That they’re not even a person in their own right. You kind of own them in a way. And then they will come out with something so completely opposite to that. That’s when you realise: “Nope, this person is their own person. They don’t belong to me.” That’s a beautiful thing, though. The distance between people must be maintained. Siblings especially fall out. They really do. Because, I think, they know their relationship is elastic. It can bounce back. There’s always a way back home.

Nancy: I like to say Ann is a lot of nice people. She’s a double Gemini. There’s a lot of different Ann Wilsons, right? Catch the right one, and that’s the one you want to be with.

When is your sister at her best?

Ann: When she’s playing acoustic guitar. That’s always my vote. She can make a guitar move, and come up with parts that are so cool, and so her. That’s when she’s at her most real. She’s not thinking about herself.

Nancy: Ann’s just an ingenious, funny, hysterical, driven person. She’s complex. I know her sometimes better than she knows herself. So she’s lucky to have me, and I’m lucky to have her. We’re symbiotic siblings and somehow it works. I’m not ever sure how, to be quite honest.

Personally, when have you been happiest?

Ann: The second time I fell in love, with the man who’s now my husband. I think people were laughing at me behind their hands because I was just a bubble. I was so happy and light-hearted and idealistic. Suddenly I didn’t wear black clothes any more. I was in all these colours. Pretty cute, I think.

Nancy: Falling in love makes me happiest. I went to the ocean for my seventieth birthday. It was to the same cabin Ann used to have and where we wrote a million songs. Stone Gossard of Pearl Jam has it now. It overlooks the Pacific, all the way north and south. It was a glorious sunny weekend. Sue Ennis was there. Geoff was there, my soulmate and best friend. Music was all around and there was lots of chocolate involved. It was super-happy. I’ll live on that one for a while.

And at your lowest?

Nancy: Lowest is loss. Losing a mum. Losing a marriage. But, you know, you find yourself dealing with that in a creative way a lot of the time. Even the greatest of sadness translates into something creative for me because that’s my armour.

Ann: Maybe in the nineties when I was recovering from the eighties. I wanted to be alone and stay in the house and watch movies. I pulled out of it. I have some really good friends.

What’s your biggest fault, or worst habit?

Ann: Trusting people too much. I trust everybody to be real and honest. I don’t feel paranoid about people. I’ve been told that’s a real fault. I mean, you have to be careful with people. I do think of myself as a strong person. Up to a point, and then I’ll go: “Okay, no more.” I will back away. I won’t ever lash out, I’ll just withdraw.

Nancy: It used to be a lot of worse things than I do these days. I used to drink too much. I used to smoke. I used to do drugs here and there. Today my worst habit would be laziness. I don’t get off my butt enough to do the strengthening it’s going to take to get through this next year and a half. It’s the opening night of the tour. You’re on stage. The lights go down.

What are you thinking in that moment?

Nancy: It’s like the feeling of being on a rollercoaster, and going ‘chink-a-chink-chink’ up to the top of the track. And the moment the lights go down, that’s when you’re at the top. The next thing you know you’re hurtling through space. I’ve been there before, but I never feel casual or cavalier about it, ever. It’s more like: “Oh shit, here we go!”

Ann: That’s when everything’s okay. That’s when the nerves go away. Maybe five seconds into the first song, everything’s going to be fine; I mean, knock on wood. That’s when you’re an astronaut inside the nose cone. You’re about to take off. There’s nothing you can do about it. So you have to just relax, strap in and enjoy it.