It’s hard to be the third movie in a trilogy. These conclusions are often saddled with the responsibility of emotionally resolving not just themselves, but an entire overarching story included in the two previous entries. And, on top of that, it has to make an attempt at outdoing the previous entries in some way. It’s a problem that has plagued The Godfather: Part III, The Matrix Revolutions, The Bad News Bears Go to Japan, and so on. That’s to say nothing of the disaster that is Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, so contrary to Return of the Jedi’s excellence.

It’s a problem that Christopher Nolan was hoping to avoid with his iconic Batman trilogy. Its 2012 conclusion, The Dark Knight Rises, flew back onto Netflix’s library as of July 1, 2022. So 10 years later, it’s worth a revisit to see just how well Nolan did.

After his electric performance as The Joker in The Dark Knight, Heath Ledger was planning on returning to the franchise for a third movie. Rather than endure the curse of the threequel, it seemed like The Dark Knight Rises could end the story of Christian Bale’s Batman in a way that felt natural.

Ledger’s tragic death made using The Joker again unimaginable. For a time, the trilogy was put on the backburner as Nolan finally made Inception. Then he returned to the Batman franchise looking for a fresh start. It would be “inappropriate” to address Ledger’s death in the movie, Nolan told Empire, and he rejected the studio’s idea of casting Leonardo DiCaprio as The Riddler, arguing that it felt too similar.

He wanted Bane (Tom Hardy).

Nolan had no previous connection to the character, but when David S. Goyer introduced him, he saw Bane as “something very different,” he told the LA Times: “a primarily physical villain, he’s a classic movie monster in a way — but with a terrific brain.” Buoying Bane were elements of inequality based on Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. Thus, The Dark Knight Rises was born.

Tragedy gave The Dark Knight Rises the freedom to pursue story arcs further removed from The Dark Knight. The movie jumps eight years ahead, long after Harvey Dent’s now-confirmed death. An extended era of peace has caused some conversation about turning back laws passed after he became the city’s martyr.

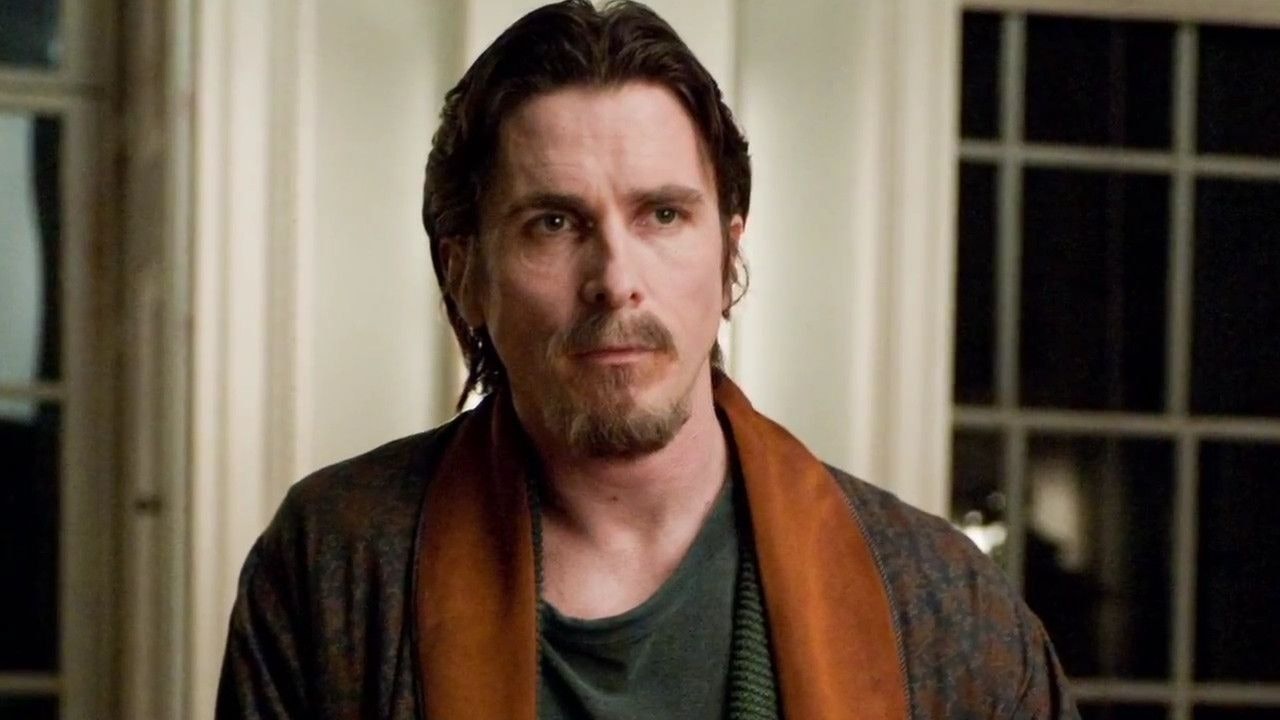

Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale), now a Howard Hughes-like recluse, learns that crime isn’t all gone when his mother’s pearls are stolen by Selina Kyle (Anne Hathaway), a cat burglar playing the role of a helpless maid. But he’s got bigger problems, like Wayne Enterprises going broke.

That eight-year time skip means that early scenes in The Dark Knight Rises have to do a lot of set-up work. Nolan walks through the Dent Act, Wayne Enterprises’ massive investment in fusion energy, and follows around Gotham City police officer John Blake (Joseph Gordon-Levitt). Outside of a dramatic plane heist at the beginning (a classic Nolan opener!) Bane doesn’t make much of an appearance in the movie’s first hour.

Hathaway makes the best use of this first hour, establishing Kyle as a survivor above all else. Nolan described her to Empire as a “grifter,” and her first-act arc of running off with a lovestruck married Congressman is a clever entry point into the criminal underworld whose ladder eventually leads up to the man with the clamshell mask and whose voice you can still hear in your head.

Bane’s voice, based on that of Irish Traveller bare-knuckle boxer Bartley Gorman, is perhaps the movie’s most-lasting memory. A little bit carnival barker, a little bit megalomaniac, and a little bit Simpsons Yes Guy, Hardy’s vocal choices define the role. It’s jarring at first but by the time he’s reading Jim Gordon’s (Gary Oldman) confession of covering up Dent’s crimes, it’s hard not to repeat every line. Bane’s voice remains one of the weirder choices in superhero movie history, and it should be celebrated for that reason alone.

Nolan introduces Bane’s uprising as a cultural revolution, an echo of the French Revolution as the backdrop in A Tale of Two Cities. There was clearly enough inequality in the real world at the time; Recall that Occupy Wall Street broke out only a few months after the movie’s release. TDKR bases its revolution on a cruel hoax perpetrated by Bane, whereas the French Revolution had real reasons that had to do with inequality caused by antiquated aristocratic social structures.

TDRK doesn’t paint social revolutions in the best light, which led Mark Fisher in The Guardian to call it “a reactionary vision” that believes that “the excesses of finance capital can be curbed by a combination of philanthropy, off-the-books violence, and symbolism.”

While it’s true that this might not be how society works, it’s undoubtedly how Batman works. He’s an extremely rich vigilante who responds to symbols lit onto clouds. There’s certainly a left-wing streak to Bane’s speeches, with his promises to “the people,” but Bane makes sure to tell Wayne that he doesn’t believe anything he’s saying.

Is TDKR arguing that all social revolutions are based on lies? I think the movie is more concerned with exploding football stadiums. The social commentary of Nolan’s Batman movies was always a little muddled. The strong performances in TDKR keep it from falling to the threequel curse, and while it’ll never persist as an iconic masterpiece like The Dark Knight, it’ll forever feel like the last decent superhero movie before Marvel Studios took over the world.

The Dark Knight Rises returned to Netflix on July 1, 2022.