In the 1980s, ninja fever swept through America. There were a few origin points for this. One was Bruce Lee: although he dîed in 1973, his legend was gaining steam. Black Belt magazine, to which Lee had contributed several articles, began in the late-’70s promoting ninja swords of dubious background.

Another was Eric Van Lustbader’s best-selling 1980 novel The Ninja. Lustbader, who had never been to Japan, wrote what reviews called an “erotic martial-arts thriller” that was “padded unmercifully with Japanese history and warrior lore.” But after he became a bestseller, Lustbader sat down with the New York Times and said that he wasn’t chasing good reviews.

“I’m out to sell books and entertain people,” he said.

He seemed to do both in spades. The Ninja, along with the NBC miniseries Shōgun, played a crucial role in the modern, Western understanding of ninjas, which he described as the people who did the dirty work that more elite Samurai would not. Then, as documented by Annalee Newitz, came Enter The Ninja and a slew of copycats.

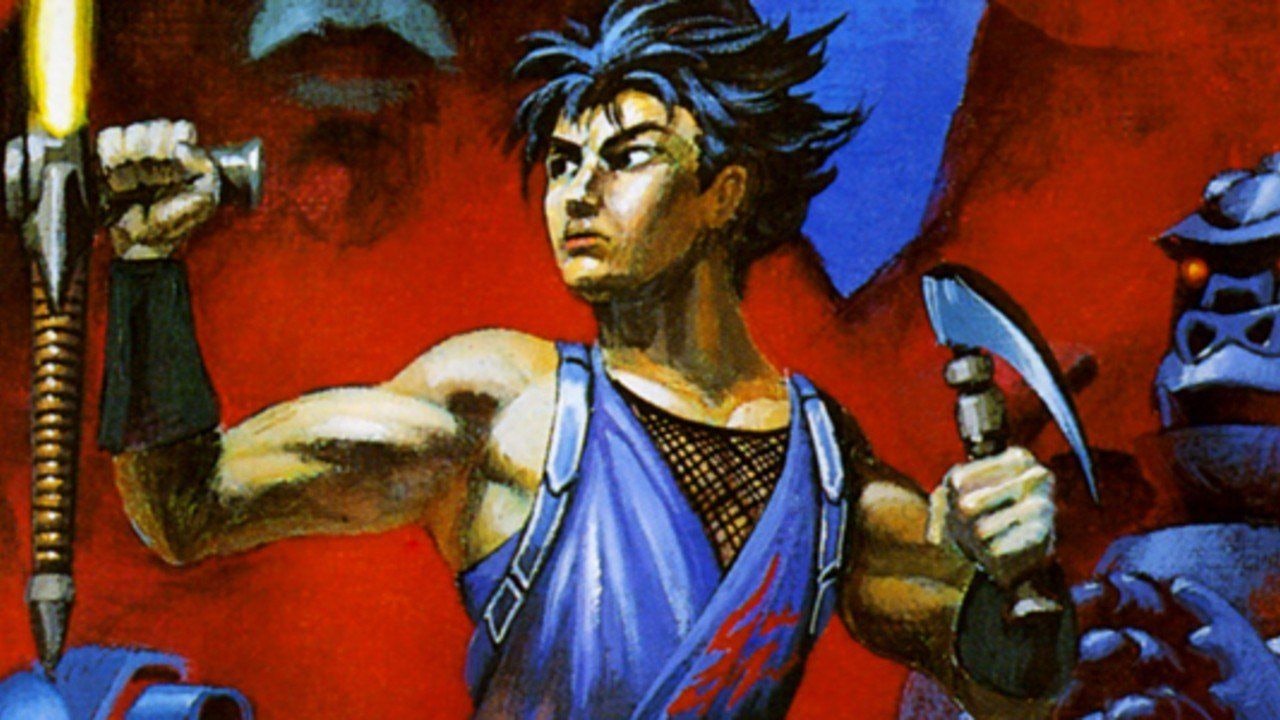

Eventually, the trend made it back home, so to speak, to Japan. When Capcom was looking to create a multimedia project with a manga studio in the late ‘80s, they packed tightly into a Tokyo Hilton for a weekend to come up with an idea. Developer Kouichi Yotsui “pushed for a ninja concept. We were leaning towards an action game, so a ninja setting would've been convenient,” he recalled in a 2010 interview.

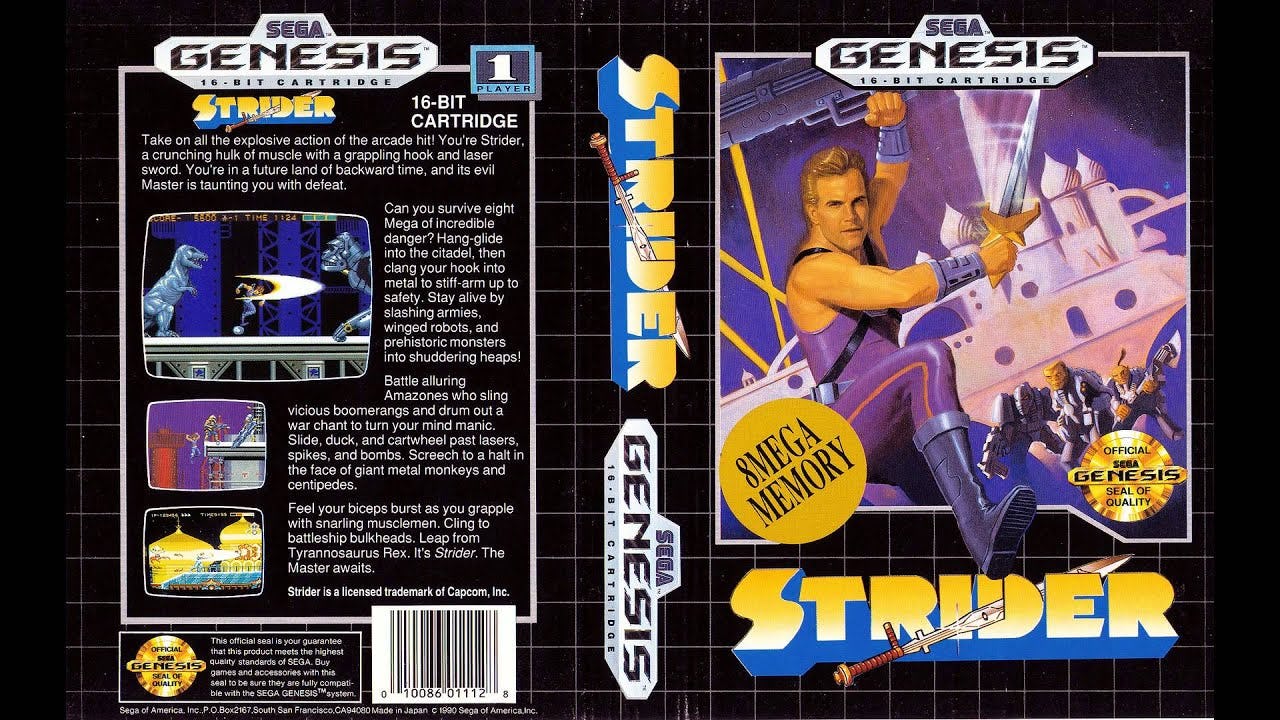

However, after years of books and movies and TV shows imagining ninjas as ancient relics, he had one demand: he “didn't want to make it some old movie.” Looking out from the Hilton into the cooler-than-cool, futuristic neighborhood of Shinjuku, he had just the setting in mind. The game that came from this meeting, Strider, wound up winning Electronic Gaming Monthly’s Game of the Year Award in 1990. The Sega Genesis version is available right now if you’ve subscribed to Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack.

Strider shows its age in its futuristic imagining of the Soviet Union, which would collapse shortly after the game’s release. It takes place during 2048 in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, a futuristic cyber landscape filled with fire and robots.

For the modern player, Strider’s gameplay is relatively simple. The game was originally built for the arcades, and it certainly plays like a coin-operated game, with controls derived from an eight-direction joystick with buttons for jumping and attacking. Strider’s main weapon is a plasma sword based on a tonfa that flashes white light across his enemy, be they human or robotic. He starts off with only three measly bars of health.

Like any good cyber game, Strider makes itself better with upgrades. Strider can get three robot buddies, who are called Options—A, B, and C. A is a cute little mushroom-shaped bot, B is a cyber-tiger, and C is a robo-hawk. Any Option is a good option in my book. These guys are great.

They came directly from Yotsui’s inspirations, which included Sanpei Shirato’s 1960’s manga Kamui Garden. Based on the manga as well as popular shooters of the time, they’re stylish enough to be the game’s calling card, even though they don’t always last long.

“After becoming bored from talks at the hotel in Shinjuku, I escaped to the hallway,” Yotsui says elsewhere in the 2010 interview. Leaving the crowd behind, he “sat on the sofa out there, and comfortably took some notes.” He was trying to figure out “how far could I take an action game with 1 lever and 2 buttons?” Strider is the answer.

While it won’t overwhelm any player today, Strider remains a gorgeous game, cutting-edge for its time. It has an epic feel to it, even if the gameplay beyond the Options can feel a little repetitive. It’s a welcome blast from the past, a vision of a future that was radically different than any throwaway ninja craze. It was built with a vision, and that's why it’s worth playing today.