Whenever one piece of art comes along that changes culture as we know it, we tend to look at it in a vacuum. But real life doesn’t work like this. Behind every piece of art, there are artists working in a specific time and place, carrying along with them the influences and mood of the era. Throughout the 1970s and early ’80s, the Japanese toy company Nintendo began experimenting with electronic gameplay: virtual skeet shooting with plastic guns, handheld gaming devices, and so on.

Who could have predicted what would happen in 1985 and the lasting impact it would have on the entire entertainment industry?

The oil crisis of the 1970s halted Nintendo’s usage of plastic, and promising developments in electronic gaming encouraged the company’s first video game hit: Donkey Kong. The game’s developer and director, Shigeru Miyamoto, was interested in what he called “athletic games,” or ones that involved a character running around and jumping, often onto various platforms. (Gaming culture would eventually settle on the term “platformer.”)

Miyamoto’s interest in this manifested in maze games like Devil World, side-scrolling games like Excitebike, and beat-’em-ups like Kung-Fu Master. Working on these smaller, unremarkable games helped to refine Miyamoto’s vision for something different: “a new game where you can strategize while scrolling sideways over long distances,” he described in a Nintendo retrospective. He wanted more movement and colorful backgrounds, a game that was easy on the eyes.

All of these elements came together in 1985’s Super Mario Bros., a cornerstone of gaming history that’s available right now if you’ve subscribed to Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack.

What can be said about SMB that hasn’t already?

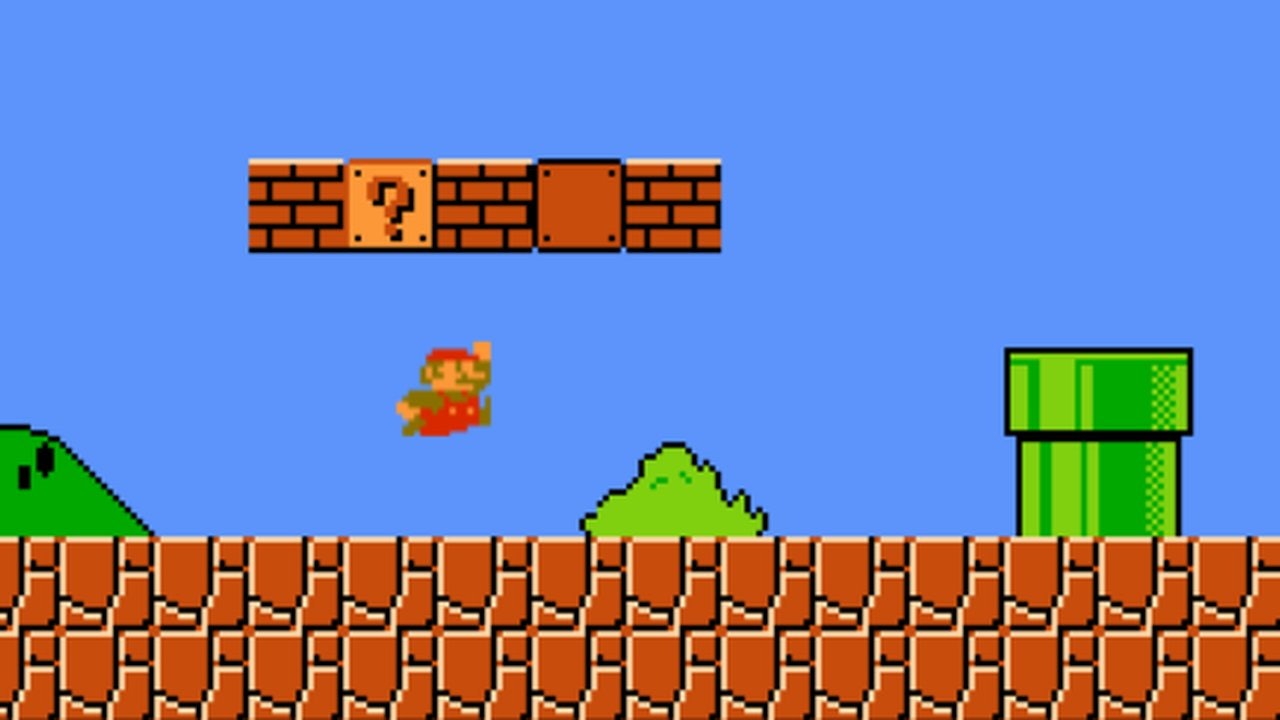

World 1-1 is a masterclass in teaching a player how to play a game. There’s short Mario, there’s the Goomba walking toward him, and there’s the beckoning question box. Hit the box and you’re big Mario. Hit another box and you’ve got fireballs. It’s simple, elegant, and creative.

World 1-2 is less heralded but equally fascinating in how it builds on and complicates the player’s experience. Mario heads into a warp tube and leaves the sunshine for an underground level, where the Goombas and turtles take on a dark blue hue. Through a lucky jump, I ended up bypassing most of the level and headed straight to the Warp Tube at the end, allowing me to jump between stages. Feeling myself, I jumped to World 4.

Then the game became noticeably harder. Now the turtles had spikes on their shells, Bullet Bills were flying at me, and some annoying guy in glasses in a cloud kept dropping more and more problems right in front of me. I could feel the degree of difficulty increase in front of me as easily as I could see it.

Higher levels getting harder isn’t a concept SMB invented, but the way the game portrayed the idea was revolutionary. Its levels looked different from each other, sometimes radically. Unlike the one-screen world of Donkey Kong, a player could never be exactly sure what was coming next in Super Mario.

The game’s world feels rich and surprising, especially when you hit the air and end up with a box, or somehow walk over all the dangers and easily make it to the level’s end. Without pushing itself on players, Super Mario offers a level of choice that was completely unexpected in 1985: Do you want to travel down this tube or that one? Do you want to break these blocks or not? It’s your choice.

The world of video games would never be the same.