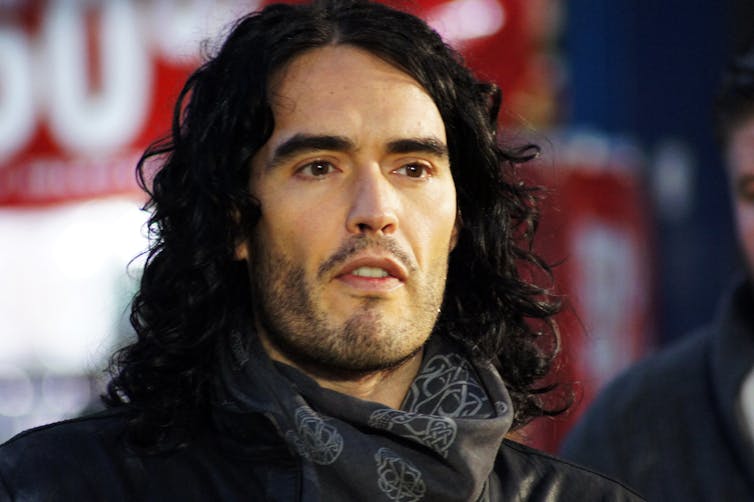

A recent investigation by UK media outlets has uncovered a number of sexual assault allegations against Russell Brand, a comedian and TV presenter. Brand has denied the accusations, however this is a timely reminder of the urgent need to challenge and address power asymmetries – not just between men and women, but within workplaces, and particularly across the creative industries.

People may work for little or no money, often for experience or exposure – typically in the hope that future opportunities may follow. We call this “hope labour”. This phenomenon is widespread, especially among those in the earlier stages of their working lives.

Hope labour is distinct from free labour because the work is discounted against imagined future opportunities or earnings. But our research shows it also creates a power imbalance: in hoping to gain experience or make connections in your chosen industry, you might be so eager to get a foothold that you leave yourself open to exploitation in terms of working hours, pay and conditions.

In the creative industries, hope labour is widely understood as a necessary pre-condition to paid work. There is a need for people to “prove that they deserve to earn their living”, as one person told us when we spoke about their experiences in the creative industries. This is how exploitative labour and working conditions become the responsibility of the hope labourer.

This form of self-exploitation is often understood as a rite of passage, or an obligation, even if it has a wider negative effect on the labour market. By working for free or at reduced rates, hope labourers downgrade the value of labour in the very sectors they wish to work in. They effectively become the gravediggers of their own and their peers’ careers.

And hope labour is only possible in certain settings. Creative and cultural jobs are often characterised by self-employment, uncertainty, project-based work, long hours, inequality and competition for scant opportunities. The resulting risks – not getting enough work to pay your bills – are transferred to workers, while employers are freed from the costs involved in standard employment.

The rise of freelancers

Work in TV and film has transformed over the last 30 years. Freelancers make up over a third of broadcasters’ workforces, although many previously worked in-house.

Recruitment and vetting for freelance teams are often managed through informal social networks. Commissioning editors use their connections to build their teams.

And commissions are given to independent production companies, which can reduce, if not absolve, broadcasters from the legal responsibility for hiring labour and managing production.

People, therefore, see social networks as important gateways to work that ought to be extended and nurtured. To gain access to these groups, undertaking unpaid or under-compensated work in the creative industries can be considered a necessity – or even an opportunity – rather than a hindrance.

This leaves hope labourers both keen but also at risk of exploitation. They need to build experience, reputation, exposure, or simply maintain access to work opportunities.

Our research also shows that being passionate about your art or work can help to downplay the severity of these risks and unequal power relations. It creates a “cruel optimism” that you can turn experiences of uncertainty and vulnerability into future security. In this way, work isn’t simply about earning, it’s a way to build reputation, gain creative freedom or fulfilment, and learn or enhance skills.

Getting a reputation

Reputations are important and travel widely in the creative industries, especially if you can keep your cool during tricky shoots or moments of stress. One freelance artist and curator that we spoke to during our study of hope labour among creative freelancers, admitted:

there’s a trap that people fall into. I’m going to sound like a psychopath here, but that you have to be really nice with everybody all the time and that you have to be everybody’s best friend … People are trying to extract value from your time and they’ll keep taking that value if you keep giving them it as well. So you have to be careful with that.

This is how the exploitation of hopes and desires in creative work and employment creates persistent power asymmetries. When your working life is governed by anxiety and insecurity about your next contract, project or job, you might be unwilling to speak out for fear of reputational damage or reprisal. And the precarious working conditions in creative industries provide few safe spaces for dialogue and critique, rebuke and reform.

This leaves people open to witnessing or even being subject to the kinds of situations that have been alleged by the joint investigation into Brand. Production staff interviewed by Dispatches talked about “acting like pimps to Russell Brand’s needs”, hinting at a reluctance to upset the “talent”.

In the wake of the reporting, Philippa Childs, head of UK media and entertainment union Bectu, told broadcasters: “In a sector where power imbalances are particularly extreme and the environment for junior freelancers can be incredibly precarious, it’s critical that victims can have confidence that their complaints will be taken seriously, investigated thoroughly, dealt with swiftly, and perpetrators held to account.”

The recently formed Creative Industries Independent Standards Agency (CIISA) offers the beginnings of an independent body for raising concerns about poor behaviour, workplace safety, and advice and protections. This could provide a way to challenge the disproportionate effects of a deregulated labour market on these freelancers.

If so, desires and hopes could be directed towards helping creative workers critique the way their industries are governed and managed. Hope, in this sense, would point to a different future that could be about fairness, equity and safety for all.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.