Those who've changed jobs or taken a promotion are keeping up with inflation, but those who stayed in the same roles are falling far behind, says Reserve Bank chief economist Paul Conway

The 28,600 workers in recruitment, rental and real estate services pocketed an average 10.8 percent pay rise in the year to September.

Pocketed? Well, not quite. Given that's taxed at a higher PAYE rate, and what's left is absorbed by a 7.2 percent rise in CPI inflation, and additional hikes in mortgage interest rates, most would have ended up no better off than they were a year ago.

According to Statistics NZ's quarterly employment survey, recruiters, estate agents, and accommodation and food services workers got the highest pay rises over the period – although some of that is through changing jobs.

READ MORE: * Don't blame the workers: NZ escapes wage-price spiral * Behind the 12% pay rise for Countdown staff

By contrast, salary and ordinary time wage rates for teachers and other education professionals have risen only 0.9 percent in the past year – which is about a 6 percent decline in pay, in real terms.

"Everything has just become harder – utilities, water, power, gas," says Auckland primary teacher Kahli Oliveira. "You do think about it when you need to fill up with gas. A lot of teachers can't afford to live where they work, so the cost of commuting is an increasing issue."

Primary teachers and principals "unequivocally voted" this weekend to refuse the Ministry of Education's collective pay offer; secondary teachers began meeting and voting on Monday. At $6,000 over two years, their offer works out half the current rate of inflation for most teachers.

“Teachers are leaving the profession because they can be paid more and have a work/life balance," says PPTA president Melanie Webber.

She's not wrong. Reserve Bank chief economist Paul Conway tells Newsroom that those who changed jobs or won a promotion in the past year are keeping up with inflation, and in some cases exceeding it. (First Union negotiated a 12 percent raise for Countdown workers, though from a low base).

For those who are still in the same roles they were a year ago, there is a chance to jump on the speeding inflation train by switching jobs – but time is running out.

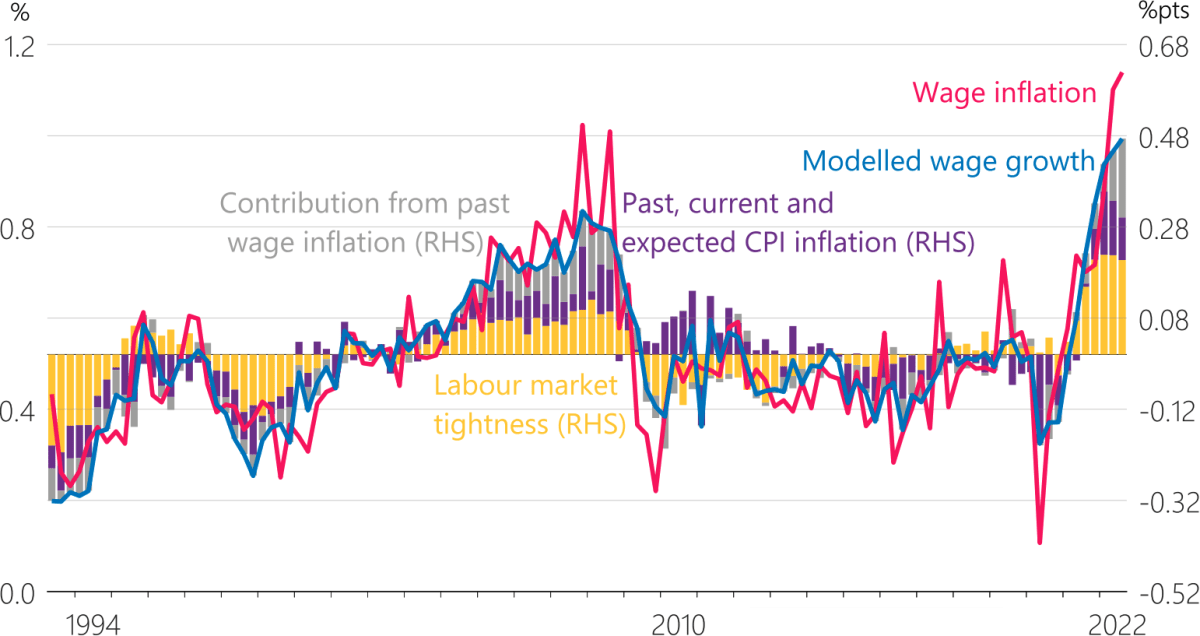

The difference is highlighted in Statistics NZ's labour costs index, which shows companies increasing wages much slower than inflation, and its quarterly employment survey – in which incomes are running at or even above inflation.

"The big difference there is that [the quarterly employment survey] captures people moving between jobs within the same employer or moving employers or working more hours," Conway says. "The wage dynamics are pretty fascinating at the moment."

New Zealand and the global economy are paying for the effects of the pandemic and the war in Europe, he says, meaning there are still far more vacancies than there are unemployed people ... for now. The Reserve Bank is forecasting unemployment to rise to 5.7 percent by the end of 2024.

But while unemployment is till in the low 3 percent range, the pool of people who have taken the opportunity to increase their income by changing jobs is a large one, he says.

"Tough economic times, they do tend to increase inequality." – Paul Conway, Reserve Bank

And Conway should know about taking opporunities in the tight labour market: he jumped on the train himself this year. He moved from BNZ chief economist to the same position at the Reserve Bank, arguably New Zealand's most senior economist role.

"It's a market where people are making these decisions all the time. And yeah, it was an easy decision for me to make to move to the Reserve Bank," he says.

"I'm really pleased to be working at the Reserve Bank at such a critical time. I feel a bit humbled actually to be one of the seven people on the Monetary Policy Committee that makes these massive decisions around interest rates. You know, I'm feeling the responsibility of that at the moment."

He adds: "Labour is seriously in demand at the moment, the labour market is incredibly tight, and people who have used those dynamics as a reason for going out and getting another job, or working harder, they are keeping up with increased inflation."

That's inevitably increasing inequality, he says. "Tough economic times, they do tend to increase inequality. And we certainly saw that over the pandemic. People who had good digital skills could work from home, so the financial cost of the pandemic, over that period, fell on people who were least equipped to deal with it."

The extent to which that inequality has increased further should be revealed by productivity and income inequality data coming out early next year.