Review: Laurinda, directed by Petra Kalive.

The Melbourne Theatre Company’s Laurinda is a smart re-framing of Alice Pung’s classic coming-of-age novel about the racism inherent in the privileged world of private school culture.

In a bizarre twist of magical-realist fate, jaded school principal Lucy Lam (confidently and energetically played by Ngoc Phan) journeys back in time to inhabit her 15-year-old schoolgirl self, newly arrived at an elite private girls school.

Lucy must navigate the challenges of being one of the few Vietnamese students in an environment riddled with confusing new rules and systemic barriers, reigned over by a truly ghastly trio of entitled white girls called “The Cabinet”.

This strongly grounded ensemble piece is the brainchild of playwright Diana Nguyen and director Petra Kalive, who share a history of improvisational story-telling through their prior work with Melbourne Playback Theatre.

Laurinda was workshopped with the cast throughout COVID lockdowns. This focussed period of development provides a robust foundation for the work.

The show’s framing device enables Lucy to relive her school experience with an adult’s perspective. As she journeys through her teenage past, she is simultaneously participant in and witness to the key moments that shape her.

Read more: Friday essay: Alice Pung — how reading changed my life

A play of power-plays

Lucy is the recipient of a scholarship which brings her to the private school Laurinda from her state school.

Excited at first to leave her working-class suburb, Lucy’s evolution from naïve newbie to empowered valedictorian drives the action.

As she negotiates the veiled insults and power-plays conducted by the members of The Cabinet (and their obnoxious mothers), the complexities of class, racism, privilege and language are laid bare.

Xanthe Beesley’s stylish movement direction creates satisfying moments of synchronised gesture, wild dancing and ensemble choreography.

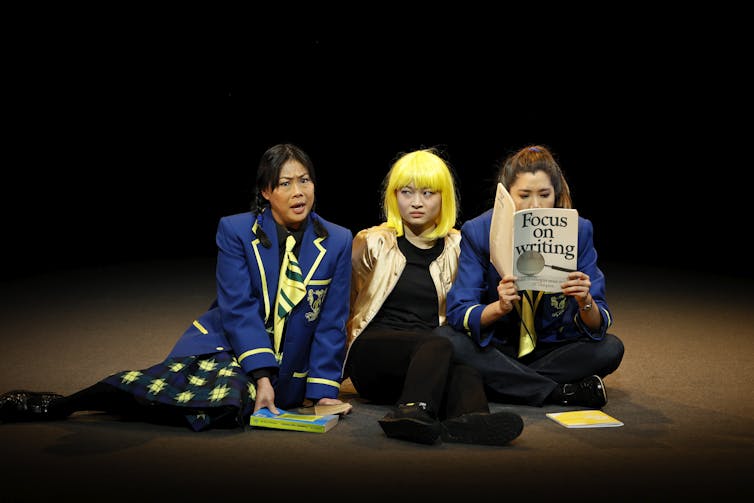

White girls and teachers are all played by an all Asian-Australian cast in purposeful disruption of racial stereotypes. In particular, Gemma Chua-Tran, Chi Nguyen and Jenny Zhou as Cabinet members Brodie, Amber and Chelsea deliver a petulant and incisive caricature of entitled white girls, complete with matching stockings and Alice headbands.

Phan switches between guileless teen and disheartened adult with great facility.

Linh (Chua-Tran) is the standout: joyful, subversive, questioning, she’s Lucy’s nemesis, friend and provocateur.

Laurinda brings the story of migrant workers and their aspirations into stark relief. Lucy’s mum (Chi Nguyen) is a gently sensitive portrait of the hard-working and no-nonsense mother, speaking rapidly in Vietnamese and English as she labours over the sewing machine.

Exchanges between mother and daughter are sometimes comic, sometimes heated, but always poignant as they grapple with clashing cultures, expectations and the echoes of intergenerational trauma.

Set in the late 90s, Nguyen’s snappy dialogue is underpinned by darkly comic overtones referencing important events of the time including John Howard’s disturbing “children overboard” affair and Hanson’s “swamped by Asians” rhetoric.

Read more: From Tampa to now: how reporting on asylum seekers has been a triumph of spin over substance

But the show works on several levels. It is also an indictment on the small-minded and entitled culture of private schools where the politics of exclusion are alive and well.

The private school setting uncomfortably resonated for me. A product of that privileged culture, I squirmed in my seat as I was reminded of the desperate gentility that pervaded my school experience: the imperious teachers, the cliquey girl groups, the sensible shoes, the social hierarchies, the recitation of the school motto.

Here, the pretentious civilities belie the glaring injustices just beneath the surface.

Witty and relevant

Eugyeene Teh’s audio-visual design is a delight. Glitchy and fractured animations vie with video closeups and swirling animated vortexes to shift us from present day to past; to manifest a plummy-voiced school marm; to transport us to a 90s dance club.

His set design, employing large elevated columns and roll-away rest-rooms, is suitably minimal, modular and stylised.

Composer Marco Cher-Gibard’s sound design includes the use of microphone reverb to build sonic depth.

As stories are told and retold through generations, they are transformed but not reduced. Witty and relevant, Laurinda successfully intersects engaging personal story and driving social commentary with intelligence and humour.

The politics of power and prejudice is explored in a perceptive work that exposes the pomposity of private school culture and reminds us systemic racism is complex and deeply embedded.

Laurinda is at Melbourne Theatre Company until September 10.

Kate Hunter does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.