Microwave scorers can take over games but are often tough to rely on. Jabari Smith Jr. valued consistency instead, which, perhaps, led him to the oven. Ten-year-old Jabari loved basketball and football, but for a time, struck by curiosity and boredom, he made his name in the kitchen. His mother had a friend who owned a bakery, and Jabari would dial her in search of recipes. He’d take stock of the kitchen, then call Mom during the week with requests. We need more sugar. Please leave my eggs out. And every Friday, upon returning to his home in Fayetteville, Ga., he got to work, following instructions, each step pivotal to his goal.

Nobody was quite sure what had drawn Jabari to baking. His mother’s best hypothesis centered on her electric mixer and the amusement of its whirring. Maybe the fun was in the process. Though it wasn’t all perfect, Jabari was willing to take liberties. There were failed experiments with food coloring, a blue cake here and purple icing there. He remained meticulous when it counted, and the proof was in the results. With an eight-inch round pan as his canvas, Jabari began churning out three-layer cakes from scratch, by all accounts delectable and, most frequently, strawberry-flavored.

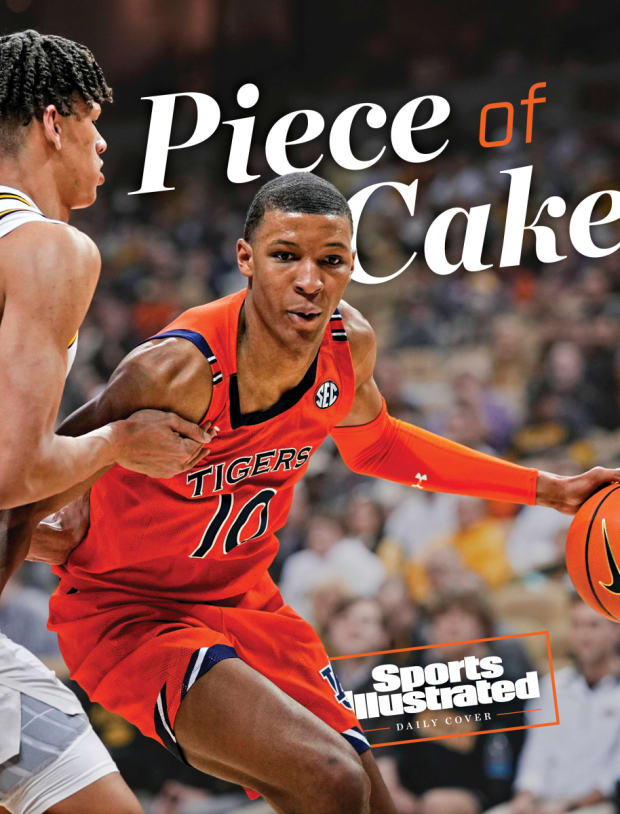

Jay Biggerstaff/USA TODAY Sports

In Georgia, Saturdays are, of course, for football. Most weeks, Jabari would arrive in his pads with cake to share. His reputation in the neighborhood soared. Requests poured in from his teammates and their families. “It got to the point where people would say, ‘If he bakes me a cake, I’ll buy the stuff,’” recalls his mother, Taneskia Purnell. There was only one snag in the operation: To play on offense and run with the ball, Jabari had to make weight the morning of each game. He loved it just as much as basketball. He’d fall asleep with his football—his baby—in hand. So Jabari held himself to a higher standard: There would be no sweets or junk food on Friday nights, which included his own handiwork. As the saying goes, you can’t eat it, too.

“He’s been like that a very long time. It’s just in him,” Purnell says. “It's not like somebody said, ‘Hey, you better do this.’ He just does it. But if you give him a suggestion on how he should do something better, he'll listen to you. And if it works, he’ll stick with it.”

As high school neared, Jabari moved on from baking (and football) and poured himself fully into basketball. This was probably inevitable: He grew up toddling around the house draped in his 6'11" father’s voluminous jerseys and sneakers, and tailing his older brother, A.J., to games and practices. Jabari Sr. spent parts of four seasons in the NBA and would put his sons through drills in the driveway most mornings before school. Today, as a potential No. 1 draft pick with a reputation to protect, Smith Jr. claims not to remember much about his culinary phase, other than the fact that his creations would disappear quickly. When pressed, his recollections differ from his mother’s in one crucial way.

“I tried not to eat [the cake] too much,” he says, “but anytime I wanted, I’d probably get some.” Smith says, grinning. “She probably didn't know about that.”

John Reed/USA TODAY Sports

It’s late January, and Smith sits covered in sweat, the face of an Auburn team that’s just grabbed ahold of the No. 1 ranking for the first time in program history. While typically punctual, he ran late for this particular conversation, which he’d already asked to push back, as it turns out, to cram in an on-court workout before film and practice. Seated in a VIP lounge inside Auburn Arena, Smith is apologetic. He spread-eagles his 6'10", 220-pound frame beneath a table designed for smaller people, catching his breath. Everyone at Auburn knows his stay won’t be long, but he’s comfortable here at school. Smith is frequently spotted at football games and women’s basketball games, and he rides around draped over an electric scooter. “There ain’t much he don’t like,” as his father puts it.

As a five-star recruit, Smith could have gone to the G League or overseas on his way to the NBA draft, but he wanted to play in the SEC, where his father played at LSU, and where he felt he’d find the most competitive environment. “I really just wanted to do it the right way,” he says. Auburn is just an hour’s drive from home, but Smith has returned only a few times since the spring, and he typically packs light. He still cooks from time to time, but the Tigers by and large run on takeout. The dorm room he keeps especially tidy is two minutes from Auburn’s facility, so he chose to leave his car back at his mother’s house. And while Smith is yet to turn 19, he phones home only when it’s important. Every so often, he’ll call his mom and ask her to go run the engine.

“I was [always] kind of independent,” Smith says. “My parents never really babied me or nothing like that, so I was always doing stuff on my own, taking care of myself. I was kind of just anxious and excited to get on campus and see how I could carry myself without my parents with me. … I was excited to just grow up.”

Since arriving on campus last spring, Smith has accomplished quite a bit, throwing shame on oddly modest expectations for a player his caliber. There was no high school All-Star circuit last year as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, so while he was named to the McDonald’s and Jordan Brand games and the Hoop Summit, Georgia’s Mr. Basketball showed up without commensurate fanfare. Through 27 games, Smith is averaging 16.3 points and 6.7 rebounds, a modest 27.8 minutes by design to help keep him fresh. While he’s making just 43.8% of his field goal attempts, he’s shooting a scalding and near-equivalent 43.3% from long range. He’s also become the team’s most versatile defender, switching screens, disrupting the passing lanes and denying errant shooters. In December, he moved to the No. 1 spot on Sports Illustrated’s 2022 draft projection.

Nothing about Jabari Smith Jr. is particularly flashy—his highlight reels consist primarily of difficult shots, which don’t always look that challenging, mostly because he’s the person taking them. There’s a balletic style to Smith’s scoring progressions, the way he shoots off midair pirouettes and relies on jab steps and toe taps while sizing up defenders. He is not a flashy dribbler, nor does he need to be. If he takes a shot you’ve never seen him try before, rest assured it’s been drilled behind the scenes.

“A good shot, I feel like, is just in the spots for me,” he says. “It just can't really be nothing that you wouldn't shoot again. It’s gotta be a shot [in] the flow of the offense or the rhythm of the game.” It helps that Smith entered college with an advanced understanding of where his shots should come from, and Auburn has worked to get him the ball where he’s most comfortable, in pinch post situations and along the baseline. When the ball finds him consistently, Smith can dominate games without hijacking possessions: Consider his career-high 31-point showing against Vanderbilt on Feb. 16, in which all seven of his made threes (one all the way from the Auburn logo) came in quick, decisive moments.

The basic tenet of Smith’s success is refreshingly simple: Most any movement can set up his jumper. Give Smith breathing room, and he’ll probably beat you. His mechanics are clean and unfettered, his lower body always balanced. With the snap of his wrist as the ball spins off his index and middle fingers (preferably, never the pinkie), each shot seems to leave his hand the same way. For an observer tasked with describing Smith’s jump shot in words, simply watching him shoot up close for five minutes is to bathe in hyperbole, most of which is cliché, some of which is unfit for print. As one veteran NBA executive observing Auburn warmups recently put it: “It’s like, almost mesmerizing.”

Jabari Smith Sr. noticed his son’s comfort level as a shooter early on and poured their time into the fundamentals, building his son’s jump shot through endless repetition. His father also had a soft touch from the perimeter but made his living as a bruising center in the early 2000s, when bigs were rarely asked to stretch the floor. Smith Sr. believed the end of his NBA career was expedited in part by the arrival of international talent, and took note of the types of tall, skilled players arriving from Europe. Smith Jr. wasn’t strong enough to push people around, but he could always shoot over them. Father and son leaned into the work together. Nothing was hurried. “He's been true to his craft from the beginning,” his father says.

The philosophy was simple enough. There would be no value placed on national rankings, much less how many points Smith Jr. scored on a given day. Defense was paramount. And no matter how tall he grew, he would prepare to play all over the floor. “It was so technical and on point,” Smith Jr. says. “Everything had to be compact and done the right way, with a sense of urgency. That’s just kind of how he raised me, just listening to it and learning. You don’t understand what he's doing when you’re young, but as you grow older, you recognize the reason for it.”

At Auburn games, Smith Sr.—often referred to as Big Jabari—is hard to miss, as he’s nearly always the tallest person in the crowd and occasionally enhances his visibility with a neon-orange beanie. Smith Sr. and Purnell separated when Smith Jr. was around 10 but worked together to raise their boys, living in close proximity while keeping the focus on the kids. “I think we just did our work early,” Smith Sr. says. “We’re not raising him now.” There was no tug-of-war over sharing time. They often sit together at games, as a unified front. “Jabari got a cheat code with his dad,” Purnell says, “because he tells him things that other people may not tell him. And I think it has a lot to do with his personality. How he has so many accolades but he's still always working.”

Smith Sr.’s post-NBA career spanned several continents, including a three-month sojourn in 2008 to Shenzhen, China, with his family in tow. Smith Jr.’s memories of that time are fuzzy and not entirely happy: He spent most of his fifth birthday on a flight from Los Angeles to Beijing, where the Summer Olympics would take place later that year. The Smiths had a translator assigned to their family, and, by the end of their stay, Jabari and A.J. picked up hints of Mandarin. The food was strange, and there were near-daily trips to McDonald’s. They took advantage of Shenzhen’s lush outdoor spaces, taking up badminton in addition to hoops. “I remember going to the courts and shooting and just putting away all the stuff that was bothering me,” Jabari Jr. says. Everyone recalls a surreal encounter with John Calipari, then the coach at Memphis, who was in the area on business and happened to be taking a stroll through the park. The Smiths, star-struck, stopped to greet him and took photos. More than a decade later, Calipari and Kentucky dabbled with recruiting Jabari. The coach may have come to regret no scholarship was offered that day.

As Smith Jr. grew, his father ensured he would be coached hard, then did his best to stay out of it. Entering Jabari’s freshman year, Jon-Michael Nickerson—a former college coach at IUPUI and Memphis who also played minor league baseball—took over at Sandy Creek High School. There, Smith evolved from a skinny role player into a dominant force, organically taking on responsibility and never requiring special treatment. They were state runners-up his senior year. “So many players and their parents are so concerned with, ‘Hey why isn't, say, Duke recruiting my kid?’—I never had to explain it, and [his dad] never asked,” Nickerson says. “[Jabari Sr.] was just a dad. I always respected that. If I ever had a kid that talented, I'd hope I could withhold like he did.”

At 15, before he’d earned a national ranking, Smith joined the storied Atlanta Celtics AAU program. His growth was overseen by Patrick Harper, whose son, Jared, was Auburn’s star point guard. Rather than park him in the post, the Celtics pushed Smith to play on the perimeter. Both Smiths have been frequent participants in Atlanta-area pro runs over the summer, exposing Jabari Jr. to NBA competition as early as he could handle it. There was no ducking of adversity. “I always try to keep him with an understanding that you gotta be so locked in that you gotta be prepared for some dark days as well,” Smith Sr. says. “Nobody has just perfect games every game. There's gonna be some ups and some downs. But you know, the great ones, and the good ones are able to be headstrong.

“Most kids don't know who they are, you know?” he continues. “It's a tough era to play in. You know what I mean? It's so much social media, so much hype surrounding sports these days. YouTube and Instagram, Twitter, it’s so easy to come on the court and that’s what you focus on. Like, ‘Man, I’m trying to get some highlights, trying to get attention.’

“I try to keep Jabari in a mind frame of, if you try to win every game, you're gonna get the attention. Because that's what winners get.”

Jay Biggerstaff/USA TODAY Sports

So here, then, is Jabari Smith Jr.’s recipe for a championship-caliber team, one that was widely tabbed to finish fifth in the SEC due to an influx of new faces. While Smith is the team’s lone freshman, Auburn worked the transfer portal as well as anyone last summer, securing four high-impact additions who have taken on key roles. What the polls didn’t know was how rapidly Auburn’s group bonded, learning each’s other's games over the course of intense offseason workouts and embracing newfound opportunity. “We wasn’t necessarily mad about it,” Smith says of the preseason prognostications, “but it was like, if that’s y’all thing, let’s just prove y’all wrong.”

Auburn’s first loss came in double overtime to Connecticut in the Bahamas, a game where Smith struggled in the first half, then dominated the second. The Tigers subsequently ripped off a 19-game winning streak, which again ended in overtime Feb. 8 at Arkansas. Smith’s maturation has been a boon for coach Bruce Pearl, who, on Jan. 28, with Auburn riding high at 19–1, landed a hefty contract extension that will pay him more than $50 million over eight years.

The Tigers now rank third in the AP poll and sit 24–3 with four regular-season games left. It’s an understatement to say they play with personality: There’s gnashing of teeth and chest-thumping, and they are almost always the aggressors. Pearl prides himself on developing depth and relies on his bench to keep the starters fresh while forcing opponents to play uncomfortably fast. Their guards pressure the ball early and often, backed by the formidable duo of Smith and 7'1" center Walker Kessler, who leads the country in blocks per game and block rate.

An Atlanta-area product, Kessler spent most of his freshman year at North Carolina riding the bench on a team with too many centers and is now a candidate for postseason accolades. He’d been a five-star recruit and one of the top transfers available, in demand to the point that Duke and Gonzaga wanted him, despite already having centers in the fold. Smith was familiar with Kessler from high school and got involved.“I knew he was real,” Smith says. “I know how hard it is to score on him, I knew he's the big I wanted to play with. I knew what he could do and what he was capable of.”

So, in the midst of Kessler’s final recruiting zoom with the Auburn staff, a familiar face popped up on screen. A grinning Smith personally invited him to the party. The message was simple: We can be the best frontcourt in college basketball. “Our versatility, our unselfishness and our ability to play on both ends,” Smith says, “not too many people have that at the four and the five.”

Auburn hasn’t always had this type of size, but it’s often relied on undersized guards, as Pearl appreciates their toughness and prefers to play uptempo. The Tigers did their homework and refitted their backcourt with three chaos agents, defined by differing skill sets and similar energy signatures. Charleston transfer Zep Jasper, the lone senior in the rotation, provides the steadiest hand as a distributor, rarely taking risks on offense and defending with intensity. In contrast, sophomore Wendell Green Jr., who arrived from Eastern Kentucky, plays a delightful and occasionally dangerous helter-skelter style. “Wen, that’s my boy,” Smith says with a chuckle. “You don't know what you’re gonna get. He’s not the type to just sit back and run a play. He’s just the type to make plays. He’s gonna make a big shot when you need him.”

Then there’s K.D. Johnson, a six-foot, 200-pound fireball who defected from SEC rival Georgia. Johnson has become a cult-like campus figure for his scowls, howls and things like leaping headfirst into the school band after wayward basketballs. “What people don’t realize,” Smith adds, “he’s always encouraging. He’s not gonna get mad at nobody for looking him off or nothing like that. He just looks that way.” Johnson’s decisions can sometimes be questionable; the utter lack of chill can be contagious.

With the five newcomers leading the team in minutes, Auburn’s returners from a disappointing 13–14 season have taken a back seat, stabilizing the rotation with experience. “They were accepting and understanding,” Pearl says, “not just because those guys were such good players, but they wanted to win, too.” Allen Flanigan, who averaged 14.3 points as a sophomore, is down to 6.9 per game. Fellow junior Jaylin Williams has tutored Smith on his role in the offense while accepting a job as his direct backup. “I feel like that’s a common thing about this team,” Smith says. “Nobody hating, nobody thinking they should be in the rotation more. When Jaylin’s playing behind me, and he could play anywhere in the country, or Wendell, just like, anybody coming off our bench could go somewhere and start. But they want to be here and win a national championship. That's why I like them.”

Smith, of course, is the key ingredient, mature and confident enough to lead by example, never complaining when the ball doesn’t find him. “I didn’t want no coach to baby me or treat me differently because of how highly recruited I was,” he says. In a vacuum, it could be so easy to envy a freshman with his type of gifts, who commands attention from every direction. Smith’s willingness to do the work and earn his minutes spoke for him, and he’s added 20 pounds in the weight room. "There’s no jealousy there,” says assistant coach Steven Pearl. “Guys recognize he’s a f------ supreme talent and is going to make us better, but all he cares about is winning. He’s not selfish, doesn’t care about his shots and just wants to win. It’s what drives him.”

“As coaches we like to think we’re great, we know a bunch, and we’ll run this set or this action,” says Auburn assistant Ira Bowman. “But at the end of the day, you throw him the ball.”

As March draws closer, the Tigers are still learning to strike the appropriate balance late in games, evidenced in part by a one-point Feb. 19 loss to Florida that ended on a broken possession. Smith admits he’s struggled a bit playing in road environments and is still adjusting, but he’s also developed a reputation for making crucial shots. Auburn has played a lot of close games, and, more often than not, he’s delivered. (“I just feel like that’s when I thrive most.”) He celebrates stops the same as makes and teammates’ successes as his own.

Watch college basketball games online all season long with fuboTV: Start with a 7-day free trial!

Externally, there’s always debate as to how star players can be used better, and, due to the freedom Pearl gives Green and Johnson, there have been times the ball doesn’t find Smith enough. “As the season progresses, and when you’re playing better teams, every player gets challenged,” Bruce Pearl says. “Therefore, [Jabari] will have to continue to do a little more for us. He’ll have to force the issue a little bit more.” Still, how long Auburn lasts in March may ultimately fall on his teammates’ situational understanding of where and when to give it to him.

Like any self-respecting, budding star, Smith has big goals: win the SEC, then win the SEC tournament, then win an NCAA title, then, if you’re feeling modest, play in the NBA. Objectively, these all seem attainable. Presuming all goes well, he says he hopes to open a gym near his home, south of Atlanta, where there will be no for-profit tournaments and local kids can shoot around and stay out of trouble. He may hear his name called first in June, he may not. That’s never been the point.

“I try not to think about it too much,” Smith says. “Just making my family happy is really a dream for me.” He’s never been in a hurry, but he’s living it.

More College Basketball Features: