Will your house flood? It seems like such a simple question, but getting an accurate risk profile for a given home can vex the experts, let alone real estate agents and homeowners. Whether you are thinking about selling your home, buying a new property or staying put, getting a handle on your flood risk is essential, even if you don't live on the coast.

Asheville, North Carolina, tucked high up in the Blue Ridge Mountains and a 7-hour drive to the coast, didn’t fit the mold as a poster child for extreme flooding. But then the torrential rains came in late September. And Asheville, a town 487 miles from the Atlantic Ocean and once viewed as a haven from the ravages of climate change, became ground zero for a devastating and deadly flooding event during Hurricane Helene.

Today, Asheville is proof that extreme rain can turn a house located pretty much anywhere in the U.S. into a flood zone.

Hurricane Helene also pounded Florida, which faces more flooding this week. Residents are bracing for Hurricane Milton, which could bring a life-threatening storm surge of eight to 12 feet in the Tampa area on the state’s west coast and drop as much as 15 inches of rain in parts of Florida.

We talked to experts around the country to understand flooding risk at the property level. We will also show you a simple way to check your own risk for free.

Could your house flood? It's possible.

Indeed, there’s a new reality for U.S. homeowners, whether they live on the shoreline, far inland, at higher elevations or in the valley below: Your home is not immune to floodwaters and the property damage and life-threatening conditions that water inundation causes.

“An extreme precipitation event is probably the single-most immediate statistical risk that people in nearly every part of the United States face in terms of climate change,” said Jesse Keenan, associate professor of sustainable real estate and urban planning at Tulane University. Since 1996, 99% of U.S. counties have been impacted by flooding, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Floods are the most common and costly natural disasters in the U.S.

Still, only 4% of homeowners have flood insurance policies to help offset the costs of repairs and renovations after a flooding event, data from FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program show.

So-called 1-in-100-year storms (even 1-in-1,000-year superstorms) are on the rise. As the globe warms, for every one-degree Celsius increase on the thermometer, the atmosphere can hold 7% more moisture, which can be discharged during rainfall events. “And that means when it rains, it pours,” said Keenan. Add in increasingly warm water temperatures that act as a fuel source for storms and the threat of higher rain totals and more powerful and frequent storms increases.

Researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory estimate that “climate change may have caused as much as 50% more rainfall” during Hurricane Helene in parts of Georgia and the Carolinas. The researchers also found that the rainfall during Helene was 20% greater due to factors related to global warming.

And that raises a question that every U.S. homeowner should ask themselves: Will my house flood?

“The easy answer is, almost every house can flood,” said Jeremy Porter, head of climate implications research at First Street, a climate risk modeling firm that connects climate change to financial risk. First Street makes climate-related risk assessments available for every property in the U.S. Real estate companies increasingly use these data.

In September, Zillow became the latest real estate company to partner with First Street to add climate risk data to its on-sale listings. “As concerns about flooding, extreme temperatures, and wildfires grow – and what that might mean for future insurance costs – this tool also helps agents inform clients in discussing climate risk, insurance, and long-term affordability,” said Skylar Olsen, chief economist at Zillow.

More than 80% of home shoppers now consider climate risk when looking for a home, according to Zillow.

How to quickly check your home's flood risk

There are several places to find information for free on a home’s flood risk. Most readers should go first to one of the three largest real estate listing companies' websites or free apps: Realtor.com, Redfin or Zillow. All three sites rely on the same data from First Street Foundation, so you won't see different information on each site. If you already have one of these apps on your phone, you're halfway there.

Here's how to get your score.

- On the site's home page, enter the property address.

- On the property's page, scroll down to the "Environmental Risk" or "Climate Risk" section.

- You'll see the five risks (flood, fire, wind, heat and air). Each risk has a summary, such as "Flood Factor. Extreme. This property's risk is increasing."

- Click on the "Flood Factor" for more details. You will see a number from 1 to 10, where 10 is the highest risk. You may also see more context on your risk. For example, "This property has a 99.90% risk of flooding over 30 years. This property’s risk of flood is increasing as weather patterns change." A bar graph will show risk over 30 years. You may see additional information and a FEMA flood zone classification.

FEMA also offers flood zone maps and other tools, but they are much more complicated to use and tend to be out of date.

Flood risk models can't identify all risks

Like any model, be it a climate risk model or a financial model estimating downside risk in financial markets, a flood risk model can lack precision and fail to alert you to so-called tail events, or low probability events, especially extreme rain events that have never occurred before.

In short, no model is perfect. And just because a model says there’s a low probability of your home flooding doesn’t mean you won’t one day have water rushing into your kitchen, rising to the second floor or washing your home away in the current.

“You can’t rely on the data in these models to be super precise.” said Tulane University’s Keenan. “It’s like a general ballpark (risk assessment). But it is a pretty decent projection of the general parameters of the risk. It’s a warning, right?”

One reason flood risk assessments lack better precision is because government flood maps are “grossly out of date, and don’t include forward-looking (data) associated with extreme precipitation and climactic phenomenon,” said Keenan. Nor do they take into account smaller waterways such as creeks, streams, and other tributaries. “So, the bottom line is that you could very well be in a flood zone, without it being a legally determined flood zone (by the government).”

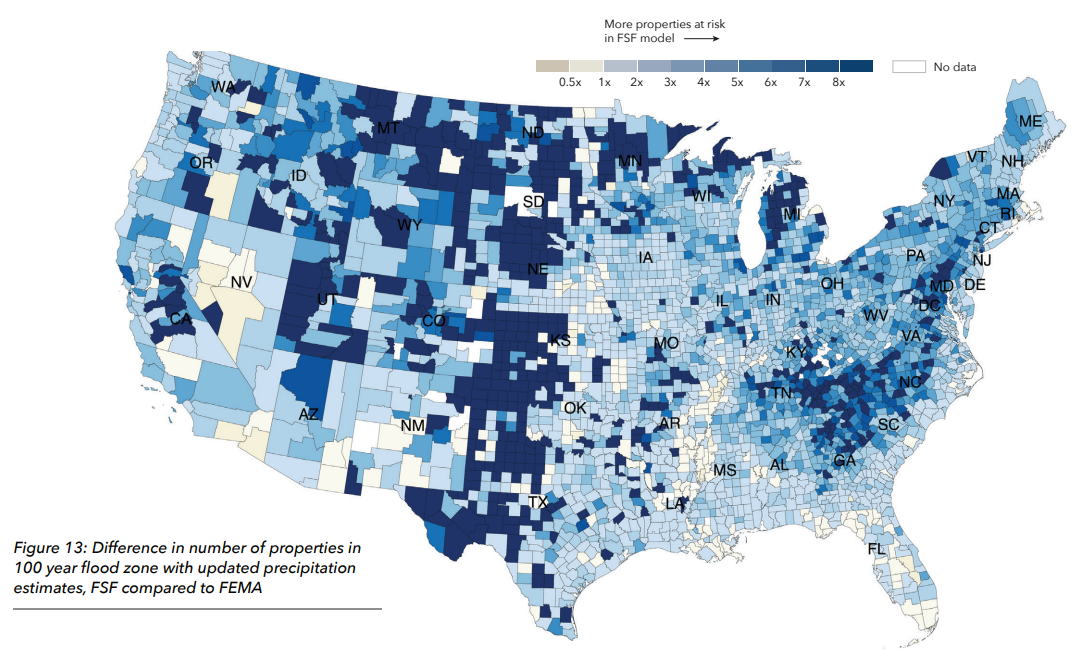

Over half of Americans (167.2 million or 51%) live in areas now twice as likely to experience a severe 1-in-100-year flood event than current government estimates, according to a First Street peer-reviewed precipitation model report released last year. In the map below, dark blue areas show the amount of flood risk First Street Foundation (FSF) found that had not been counted by FEMA. So, if you live in Florida, for example, the light shading doesn't mean your area has no flood risk; it indicates that FEMA has more accurately accounted for the number of properties at risk. If you live in a dark blue area, it means that FEMA (and probably your community) has undercounted the properties at risk compared to those found by FSF.

No model will be 100% right

Even First Street's models can be flawed.

In the case of Asheville, N.C., for example, First Street’s risk assessment didn’t fully capture the apocalyptic flooding the city experienced. While First Street said the city has a “major risk” from flooding, noting that 5,578, or 15.8%, of all properties, are at risk of flooding over the next 30 years, it ranked residential flooding risk as “minor.” Still, despite referring to a 1-in-100 flood event as “a low-likelihood storm,” First Street did note that this type of extreme event has a 26% of occurring at least once over the life of a 30-year mortgage.

First Street’s Porter acknowledges that its model didn’t fully capture the extreme rain and resulting flooding disaster that engulfed Asheville. He notes that First Street can model 1-in-500-year storms, but even modeling for that type of extreme rain event can’t capture storms of this magnitude that have never been seen before. As more current flood-related data and information comes in, that allows for fresh inputs to the models and enables climate risk professionals to update their flood-risk estimates.

“Some of the precipitation gauges coming out of North Carolina are showing like a 1-in-1,000-year storm,” said Porter. “You’re projecting a future that hasn’t occurred in the past, so there is some uncertainty around that. But it’s super important to understand that these rare tail events can still happen, and they’re likely to happen more often given the changing conditions in the atmosphere.”

Still, Porter says the intelligence the climate risk assessments his firm and real estate websites offer people involved in real estate transactions, including both buyers and sellers, is still useful. “It’s a way for us to quantify and communicate climate risk,” said Porter.

“It’s an additional data point, a lot like walkability and education scores,” said Porter. “It’s additional data that people can take into account when making decisions about where to live, where to relocate to, things like that. It’s a tool that fills in a gap for climate risk and that people can understand.”

How home shoppers can use flood risk predictions

While no climate models are perfect, they may offer insight into how exposed a property is to flooding risk and what the financial costs, such as insurance-related inflation, will be over time.

“If you want to live in coastal Miami, there’s a lot of positives to that,” said Porter. “People want to live on the beach in a beautiful beachfront community. But you should go in with your eyes wide open. You should understand what the risk looks like today, what the risk is going to look like in the future, and what are some potential solutions you can implement to protect yourself.”

No doubt, homeowners armed with flood-risk data are better able to quantify the cost of home ownership, experts say. For example, when a homebuyer takes out a 30-year mortgage, they’re expecting to pay a certain amount of money each money for principal, interest taxes, and homeowner’s insurance. But if homeowners’ insurance or flood insurance spikes by two or three times what it was when the homeowner bought the property, the entire cost structure of homeownership changes. That’s why getting an idea of how flood risk could change the cost of owning a home over time is critical for homeowners.

“It feeds directly into the household economics decision about whether the house I can afford to today will fit into my household budget (in the future) if costs rise,” said Porter.

The growing trend of integrating climate change into real estate risk and valuation is likely just getting started, adds Porter.