We’re living in a world where technology has gotten so cheap that it's entirely possible to make quality recordings from the comfort of your bedroom. Audio interfaces are available for less than $100, decent condenser and dynamic mics are even cheaper, and with abundant knowledge available online, the sky’s the limit when it comes to creating music.

The impetus to buy more gear is something the vast majority of musicians struggle with. We all think that new bass guitar will make our rock recordings hit harder, the latest AI-powered EQ plugin will up our mix game, and those expensive new studio monitors are bound to make our mastering skills much better. But will a more expensive audio interface improve the quality of your recordings?

Spending more on gear must have some effect on your recording quality, otherwise studios wouldn’t have tens of thousands of pounds worth of outboard gear inside. There's no doubt that upgrading to an audio interface from a native laptop or PC soundcard will offer a significant improvement. But at the home studio level, is a $100 interface versus a $1,000 interface really that far apart in terms of quality? Let’s find out…

Audio interface testing

The quality of an audio interface, for us, comes down to a select few factors. These measures are largely how audio interface manufacturers will test their own gear, and are what’s presented to you on their specs list. There are other components and measurements of course, but for the most part, these are a good indicator of the overall quality of an audio interface.

Equivalent input noise

Equivalent input noise, often abbreviated as EIN, is the result of output noise divided by the gain reading. A typical test is to plug a microphone into the interface with the gain turned up to the maximum and measuring the noise level this imparts. By subtracting the amount of gain from the measured noise level you’ll get an EIN figure.

EIN determines how much noise any mic preamp will add to your signal, and is why you’ll often see audio interfaces being referred to as ‘low noise’ or ‘clean’ when it comes to their mic preamps. Every mic pre adds some level of noise to your signal, regardless of its quality. A good mic pre will allow you to record quiet sources without inducing so much noise as to make the signal unusable in your recording.

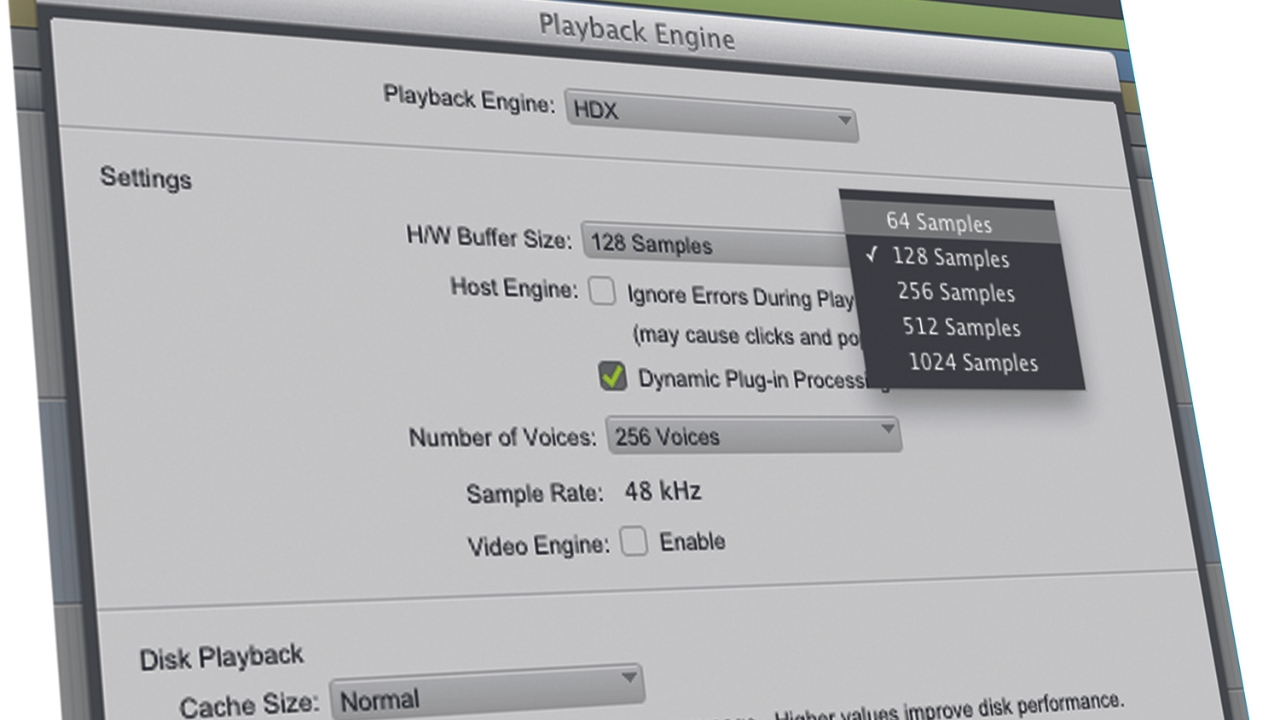

Round trip latency

The latency figure measures how long it takes for the signal to go into your interface, onwards toward your computer, through any drivers or software, and then back out to your monitors or studio headphones. This figure is partly affected by the computer you’re using, alongside any drivers and software, which means you won’t typically see this figure listed on the spec list.

Latency is important mainly for tracking, as you don’t want a delay between what you play or sing versus what you hear through your monitors or headphones. Therefore lower latency figures are better. Latency can affect the performance part of your recording which, as we’ll come to, is one of the most critical components of making great quality music. It’s especially important for those using an interface in a live capacity too.

Dynamic range

Dynamic range is the difference between the quietest and loudest sounds the audio interface can process. The quietest figure is any signal detectable above the noise floor of the interface, whereas the highest point is the maximum input signal it can handle. The wider the dynamic range of an audio interface, the more flexibility you have in terms of gain levels when micing up instruments.

Of course, it’s very unlikely you’ll be recording a source that goes from the minimum signal level to the maximum, so what it really amounts to is the room to record very loud versus very quiet signals. A wide dynamic range typically indicates that an audio interface is made from good-quality components.

Frequency response

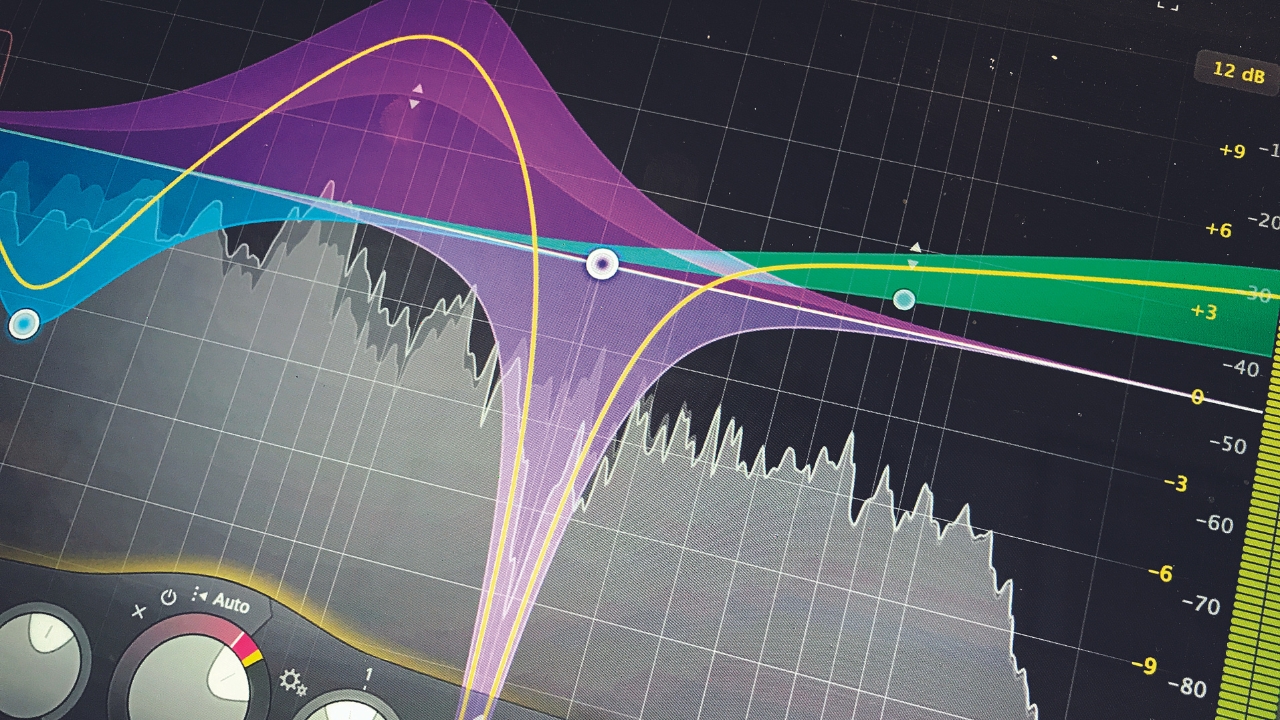

Probably the least useful of all the measurements listed here, frequency response covers the range of sounds an audio interface can replicate. Typically this falls between 20Hz and 20kHz, which covers the limit of human hearing The majority of modern audio interfaces will feature a full frequency response, and it’s pretty rare to come across anything else.

You will find interfaces with specs that give increased higher frequencies, sometimes to the 40kHz range, but this is pretty irrelevant unless recording at higher sample rates. The frequency range will sometimes be measured with potential cuts or boosts to the frequency range, usually denoted as '± 1dB'. More expensive models will bring this figure down significantly, and these cuts and boosts occur in the extreme highs and lows of the sound spectrum.

Bit depth & sample rate

Another very common specification to see is the bit depth and sample rate. The latter is the number of samples of audio taken by your interface every second. The former is the number of bits of information in each of those samples. The most common format used in music is 24-bit, 44.1KHz, although as computers have gotten more powerful and hard drive space cheaper, you're quite likely to see engineers using 48 KHz as well.

Most audio interfaces will cover 16-bit and 24-bit, with some going as high as 32-bit, however, you're pretty unlikely to see these at the home recording level. Sample rates range from 44.1 KHz, which is the standard for CDs and consumer audio, to 48 KHz which is typically used for video, and more recently in audio, ending with 96 KHz and 192 KHz. In terms of quality higher numbers are better, but the higher you go the less you're likely to notice a big jump in quality.

The problem with testing

So now we know what determines the objective quality of an audio interface, can this determine how good an interface is? Well, not really. The main problem is that manufacturers use different testing methodologies to come to these figures. For example, some interfaces might have had their EIN levels measured with the input gain cranked, whereas others might have it set at the minimum. Some might have been used with a dummy load at a certain level of ohms, with another using a different one.

Some figures can be 'A-weighted', which is an adjustment applied to readings to account for human hearing. For example, in measuring dynamic range, often a figure will place emphasis (i.e. weight) on the portion of frequencies that the human ear is most sensitive to, resulting in a different reading (and typically nicer looking) from a non-A-weighted figure.

Some manufacturers are very clear in their specs whether or not the figure is A-weighted, or what kind of dummy load was used to perform the test, but not all are like this. It means that there may be differences in what you get in the real world, versus what the spec list tells you the interface can do.

How these figures affect quality

If you go and compare specs on any modern audio interface at the home studio level, you’ll see that their specs are very similar. Compared to twenty years ago, the quality of audio interfaces nowadays is incredibly high, and most differences are going to be pretty much unnoticeable unless you have a perfect acoustic environment to listen in, or incredibly well-trained ears.

So, to answer the question proposed at the start of this article, will buying a new audio interface improve your sound quality? Yes, but only to a very small extent, one that will be pretty much unnoticeable to anyone other than professional engineers. If you have an interface that’s twenty years old, then of course a newer one will give you noticeable results, but going from a Scarlett 3rd Gen to 4th Gen? The difference in quality is tiny, it's the features that have improved.

How to improve the quality of your recordings

So if getting that shiny new interface won’t give you a drastic improvement, how can you make your recordings better? Here are some of our top tips for getting a better-quality end product:

Acoustic treatment - More than anything else, having a good listening room is going to improve the quality of your mixing, and thus your recordings. If you’ve got a budget of $/£1,000, then you should probably be spending 50% of that on treatment and the rest on studio monitors/audio interface/studio headphones. A treated room will also be better for recording, meaning less unwanted reflections and noise when using a microphone.

Composition & performance - With all our fancy gear in the modern age, we forget these most critical components of any great song, composition and performance. The performance aspect is why old recordings from the '60s and '70s still sound great today, despite being recorded with gear that would largely be considered inferior to anything available in the modern age. Nailing your timing, intonation, dynamics, and composition will do so much more for your music than buying another piece of gear.

Use reference tracks - A reference track is an incredibly useful tool that often gets overlooked in favor of the latest fancy AI mastering plugin. But reference tracks are used by pretty much every pro engineer out there, as it gives them something to aim their mix towards. Using a professionally recorded track that’s level-matched against your own, will show you what your mix is missing versus others in the genre, allowing you to make mixing decisions in context rather than in a vacuum.

Conclusion

Hopefully, that gives you a bit more insight into how audio interfaces perform, and some reassurance that you can get your music up to the same level as your peers with a little effort. We’ll reiterate that at the home studio level of interface, somewhere between the $100 and $500 mark, there really isn’t all that much noticeable difference. It’s the song itself, the room you mix and record in, and various other factors that will determine the overall quality of your recording.

Of course, once you start hitting the $1,000 mark and upwards then you will see a difference in quality, but again, you’d need an experienced pair of ears and a great listening environment to notice these differences. Try not to get too hung up on the price point of your gear and instead, focus on room treatment, getting your song to its best possible state, and using reference tracks to get your mixes to really hit hard.