I was in love with Melanie Burke.

So, secretly, I placed an English one-pound note — enough money back then to buy 10 Mars bars — into her classroom drawer.

I hoped she’d sniff out her admirer. But Melanie never said anything. And I was too shy to ask if she liked my gift.

It’s been 45 years. She could be a grandmother by now. Maybe she invested that money in Microsoft stock and is traveling the globe with her Greek boy-toy.

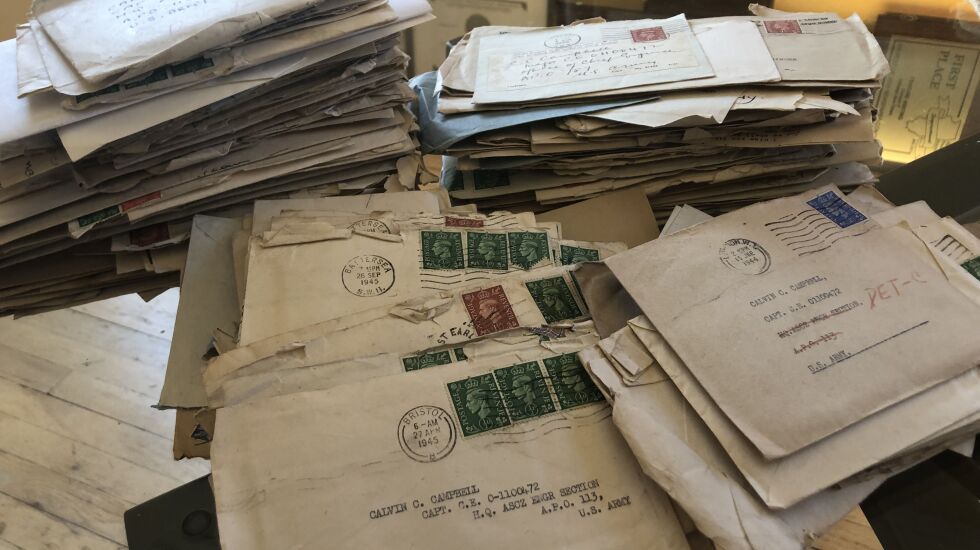

Why dredge up that memory? For the same reason I have half a dozen stacks of letters on my kitchen table — the paper onion-skin thin and crackly, the postmarks from wartime London, 1944.

Somewhere in those hundreds of letters from my English grandmother to my American grandfather, I hoped to pluck some wisdom. My oldest son is 12, and it’s time, the experts say, to have “the talk.”

Unplanned pregnancies and STDs are a future worry, of course, but that’s what sex ed is for.

The heart, that’s what troubles me.

“Lucca,” I said the other day while driving him home from school, “some day your heart will be broken. It will. There’s no way to avoid it. But please, for goodness’ sake, whatever you do, don’t spend hours, weeks, months pining over some young woman. It isn’t worth it. She will have moved on. Trust me. I speak from experience. Life is too short.”

“Dad, the only thing that will break my heart is if you don’t take me to Naf Naf Grill for dinner,” Lucca replied.

So, looking for another way into this, I began going through the letters.

Calvin Clayton Campbell, my grandfather, was a handsome officer in the United States Army — and a farm boy from Missouri. He had a girlfriend back home, but then he came to England and fell in love with my grandmother, Jean Laing.

Grandpa was part of the D-Day invasion force. Granny wrote to him almost every day while he was gone. I’ve never seen his letters to her, but he kept all of hers. A few years before Grandpa died, he handed the bundled letters to me with a note on the package that read: “Caution! Erotica inside.”

It wasn’t true. My grandmother’s voice is sweet, sometimes impatient and brittle.

“If anything should happen to you, I should love you even more. … I should inflict myself on you for the rest of my life and never leave you, darling,” she wrote six days after the invasion had begun.

She talked about her hopes for their future: “If we have a girl, dearest, do you mind if we call it Marilyn?”

Heather, not Marilyn, was born one year after the war ended.

Granny had a jealous streak.

“Darling, tell Don” — Grandpa’s dashing best friend — “that we all think he’s an absolute devil with women, but please not to keep dragging you all over these places to prove it to you — and himself,” she wrote.

Death — the possibility of it — is never mentioned in any of the thousands of pages Granny wrote. But it creeps between sentences like an icy fog.

“I still haven’t had a letter from you,” Granny wrote on June 15. “I’m beginning to feel extremely restless and I know I shall be all right once I hear from you.”

My grandfather came home safe. My grandparents married in England and had two children.

When Granny first heard stories about Grandpa’s home town of Allendale, Missouri (current population 50 or so), she imagined a life rural and quaint — perhaps an American version of a Constable painting. What she found was a mother-in-law who rung the necks of chickens with her bare hands and a father-in-law who always had a cigarette dangling from his lip.

My grandparents would eventually divorce. They were from such different backgrounds, it was an outcome not hard to predict.

My takeaway from thumbing through pages and pages of almost 80-year-old letters?

Offering advice about love is mostly an exercise in futility — like trying to pluck dust motes out of the air between thumb and forefinger.

So when Lucca comes to me, as I hope he would, and says, “The world has come to an end. How could she dump me? She said I was her soulmate!” I’ll give him a hug, do my best to listen and gently point out that this pain will not last.

Then, I’ll remind him of his very first love — and we’ll hop in the car and head to Naf Naf.

FATHERHOOD: AN OCCASIONAL SERIES

This is one of an occasional series on fatherhood by Sun-Times staff reporter Stefano Esposito, the dad of two sons.