All 19 species of Anguillid eels migrate from the sea, where they are born, to the freshwater systems in which they grow. After a period of up to 20 years, they reach maturity and return to the sea to breed and die.

These migrations have lent the eel a certain air of mystery over the years, but this has not prevented them from ending up on dinner plates across the world.

All cultures with access to eels have eaten them, and eel remains are frequently found in paleolithic archaeological sites. Indeed, some might even argue that eels, not turkey, should be the symbol of American thanksgiving: when the exhausted crew of the Mayflower celebrated the first American thanksgiving, much of what they ate was eels.

Contemporary cuisine finds multiple uses for the fish, from smoked European variants to Korean Jangeo-gui and the Valencian dish all i pebre. They are a common ingredient in many parts of the world. However, the industrialisation and globalisation of eel consumption has caused their numbers to collapse.

A moratorium on eel fishing is needed.

Whaling ban: a template for action on eels

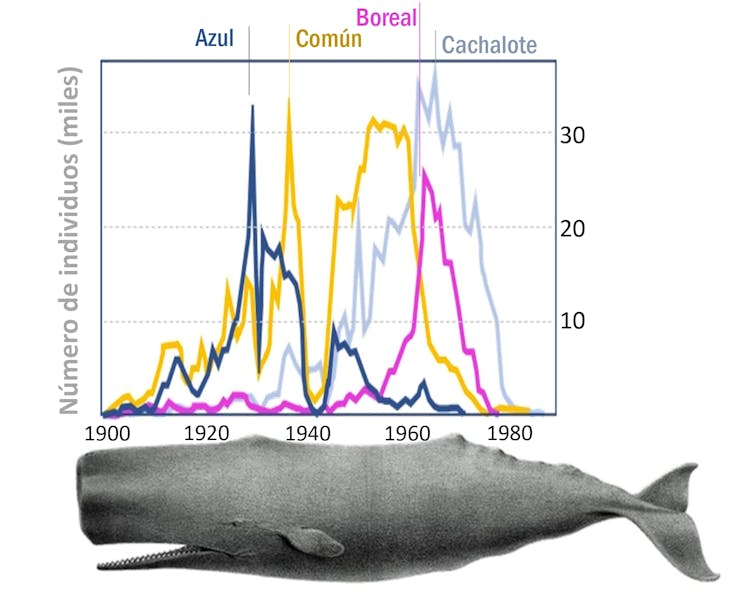

Almost three million large cetaceans were hunted over the course of the 20th century. Faced with the evident decline of whale populations, the International Whaling Commission was set up in 1946, with the mission of guaranteeing “the proper conservation of whale stocks and (…) the orderly development of the whaling industry”. Over the years it became clear that this mission had failed, as whale populations could not withstand the pressure they were under due to hunting. A total cessation of whaling activity was needed.

After several unsuccessful attempts, a moratorium on whaling was agreed in 1982, and has been in place since 1986. The role of countries without a whaling industry (such as Mongolia, Austria or Mali), as well as the support of countries that did hunt whales, among them Spain, was fundamental to reach the majority required.

Only two months before the vote, Spain opposed the moratorium because it claimed to have “absolute and truly exemplary control over whaling”. However, its last minute change of vote ended up being decisive in the ban’s approval.

Despite the vote, Spain maintained its whaling activity up to the limit of what was permitted. The Spanish whaling industry made its last catch in October 1985, when a fin whale was killed off the coast of Galicia.

The whaling moratorium undoubtedly has weaknesses, but it is a collective success for humanity. Taking it as an example, David Attenborough has said that “we know what the problems are and we know how to solve them. All we lack is unified action.”

This is exactly what needs to be done for eels.

Heading towards an eel fishing ban

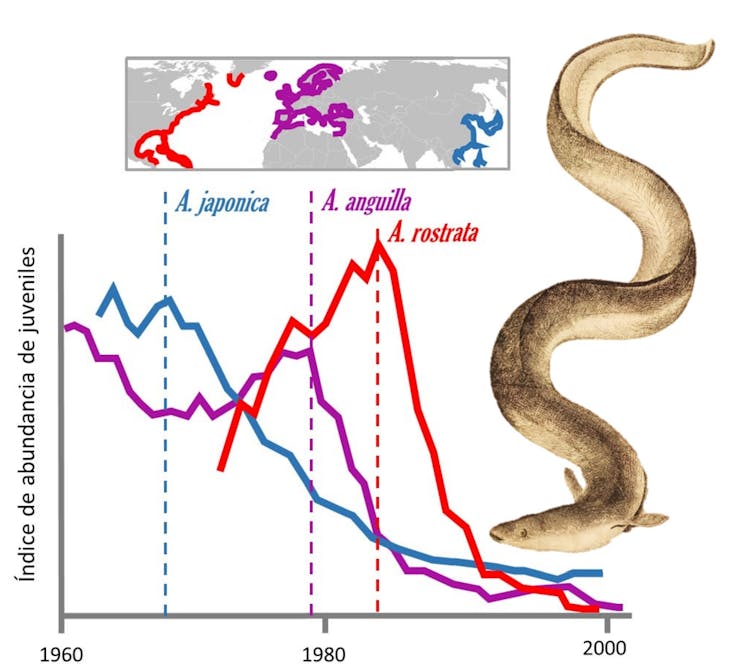

The most heavily overfished and threatened eel species are the European (A. Anguilla), Japanese (A. japonica) and American (A. rostrata). No fewer than 20 years ago, the Quebec Declaration of Concern made an urgent appeal for the protection of these fish. Ten years later the situation had not improved at all, and it remains the same today. Continued exploitation will prevent any possible recovery and will ultimately lead to their extinction.

An international moratorium like the whaling ban is the most effective way to conserve eel populations, but it is complex. Coordinated international action is essential to address the overexploitation of multiple species which are distributed across many countries and traded internationally.

The moratorium should involve a total ban on eel fishing for a reasonable period (at least a decade) and a total ban on the marketing of eel products in any form.

The global popularity of Japanese cuisine, which accounts for most of the world’s use of eel, means that the moratorium must apply to eels in general, not just specific species. Eels (known as unagi) are a ubiquitous item on menus in Japanese restaurants around the world. This massive use of eel is the driving force behind its illegal trade, which is the world’s largest wildlife crime and affects multiple species.

Nevertheless, problems with eel are not limited to law breaking, or to Japanese restaurants. Large quantities of eel are still legally eaten throughout Europe, and its consumption is promoted at various gastronomic festivals.

In Spain, glass eels, known as angula, once plentiful and cheap, have become increasingly scarce and expensive. This has led to them becoming a status symbol, leading in turn to greater intensity of exploitation, more scarcity, and even higher prices. This generates an extinction vortex which, left unchecked, will lead to extinction.

Reaching a moratorium

Coordinating international conservation action is not easy, but the whaling moratorium shows that it is possible. Decisions taken at regional or state level are important because they can be scaled up to build global agreements.

In the case of the European eel, the fishing limitations established by the European Union’s Agriculture and Fisheries Council are crucial. These decisions are supposed to follow the recommendations of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. However, recommendations to ban hunting the species have been made for more than 20 years, and have yet to be heeded. As was the case in the International Whaling Commission, the countries, regions and lobby groups that commercially benefit from eel fishing have manoeuvred carefully to maintain the activity.

Europe has a new opportunity to heed the advice of experts and implement a ban, and Spain in particular has the opportunity to change its role and move towards defending the conservation of eels, as it did with whales. Collectively, we have the opportunity to build towards a global ban on eel fishing.

Miguel Clavero Pineda does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.