The Beijing Winter Olympics will be remembered not just for China’s efforts to impress the world amid criticisms of its human rights record. The games were also held against the backdrop of the most dramatic escalation of strategic tensions between Russia and the West since the end of the Cold War.

In fact, the great power standoff over Ukraine and the never-ending speculation over whether Russia will invade have often overshadowed the international celebration of sport and unity.

The end of the games coincided with an escalation of fighting in eastern Ukraine. If the threat of Russia’s use of force against Ukraine was more speculative and often debatable just several weeks ago, the risk of real conflict is now much higher.

Russian President Vladimir Putin shows more confidence in resolving the crisis in his country’s favour than ever before. His confidence is likely to be based on the following draw cards: the faltering Ukrainian economy, Russia’s military prowess and a new trump card, China.

Economic uncertainty

Russia can be thankful to the United States and Europe for the perfect media storm they have created. The four months of anxious anticipation of what Russia might do next and the decisions by western embassies to move from the capital Kyiv to the western city of Lviv have had a damaging effect on Ukraine’s economy.

In fact, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy has even criticised the Biden administration for stoking panic over a war, saying it is hurting the country’s economy.

Adding to that, Russia is tightening its economic pressure on Ukraine by reducing the country’s value as a transit state for its gas exports. Analysts say Russian gas flows through Ukraine fell to historic lows in January, meaning less revenue in transit taxes for Ukraine.

The threat of conflict has also caused Ukraine’s currency to fall to a four-year low against the dollar and led to higher insurance for Ukrainian exports from Black Sea ports, as well as for Ukrainian airlines.

One Ukrainian economist says the crisis has already cost the economy several billion dollars just in the past few weeks.

Read more: Why Ukrainians are ready to fight for their democracy

Military muscle

And despite Putin agreeing to more diplomatic talks, it’s clear Russia is far from backing down.

Russia is prepared to continue using its reformed military power and the threat of conflict in its bargaining game with the West, despite the dangers of an actual war breaking out and how devastating it could be for Russia’s own economy.

Read more: Russia not so much a (re)rising superpower as a skilled strategic spoiler

In recent days, Russia carried out its annual strategic nuclear forces exercises, called Grom (or “Thunder”). The decision to bring them forward from the second half of 2022 seems to be deliberate act. The aim: to remind Western leaders of Russia’s status as a nuclear superpower, and the risks associated with confronting it militarily.

Simultaneously, it was announced Russia and Belarus would continue their joint exercise activities beyond this past weekend. NATO estimates about 30,000 Russian troops are currently in Belarus.

The Kremlin is confident ten years of reforms and massive injections of money have transformed the Russian army from an ageing, ill-equipped force into one of the world’s most powerful militaries. Adding to that, the Russians believe neither the US nor NATO would risk an open conflict over Ukraine.

So, by continuing to flex its military muscle in this way, Putin is expecting Western leaders to eventually pressure officials in Kyiv to submit to a political resolution of the crisis in eastern Ukraine on Russia’s terms.

The China card

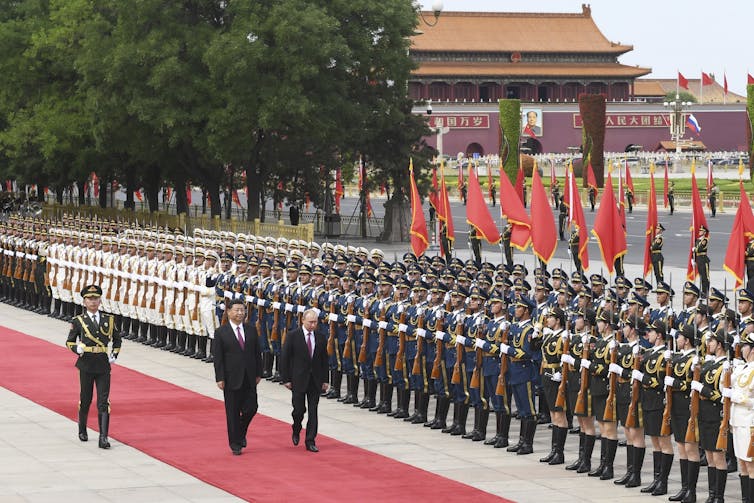

Perhaps the most powerful draw card in Putin’s back pocket is China. While Russia and China have been growing closer in recent years, a summit between Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping at the start of the Olympics sent alarm bells ringing in Western countries. Some US and European officials even said it could “amount to a realignment of the world order”.

First, the two leaders signed a long-term agreement to ship Russian oil and gas to China worth US$117 billion. This agreement allows Moscow to mitigate the possible fallout from US threats to halt the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia to Europe if an invasion occurs.

Second, the joint statement formalised China’s political support for Russian strategies against the West. Importantly, for the first time, China voiced support for Russia’s opposition to NATO expansion:

The sides oppose further enlargement of NATO and call on the North Atlantic Alliance to abandon its ideologised cold war approaches, to respect the sovereignty, security and interests of other countries.

During his speech at the Munich Security Conference over the weekend, China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, reinforced this message and backed the Russia-favoured Minsk Agreement on the political settlement of the breakaway, pro-Russian regions of eastern Ukraine.

Although Russia does not need Chinese military assistance in any potential invasion of Ukraine, Beijing’s political and economic backing is encouraging for Putin. In return, Beijing will gain serious dividends from Moscow.

First, by agreeing to back Russia against NATO, Beijing gained Moscow’s reaffirmed support on Taiwan, which China claims as its own territory. In fact, China may borrow Russia’s approach towards Ukraine as a model to pressure Taiwan into unifying, or an outright invasion of the island.

Read more: Australia's strategic blind spot: China's newfound intimacy with once-rival Russia

Second, China can now rely on Russia in its balancing game against the new AUKUS security pact between the US, UK and Australia.

Third, Xi may use his cordial relationship with Putin in his power moves at home. Later this year, the Chinese Communist Party will hold its 20th party congress – a watershed moment for Xi’s leadership. Putin is revered in China as a strong leader, so shoring up his support may be important for Xi as he attempts to secure another term in power.

For now, time is on Putin’s side – it’s a sizeable strategic factor the West does not have. And the deeper the animosity becomes between Russia, China and the West, the closer Beijing and Moscow are likely to grow.

Alexey D Muraviev does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.