Sometime after 4:30 p.m. on the afternoon of May 5, 1973, groom Eddie Sweat unlatched the front of Stall 21 in Barn 42 at Churchill Downs. Out came Secretariat.

The strapping chestnut colt likely already knew it was a race day. He had been fed less than his usual prodigious quantity of oats—Big Red had a Ruthian appetite—and the hay bundle tied up outside the stall door for snacking had been taken away. Secretariat was walked a few times around the Barn 42 shed row under the nervous gaze of trainer Lucien Laurin, then led away from the barn area to the backstretch of the Louisville, Ky., landmark. More than 130,000 people created a hum of boozy revelry that emanated faintly from the other side of the world’s most famous racetrack.

About 45 minutes before post time, Secretariat and the other 12 contenders for the 99th Kentucky Derby were turned over to lead ponies for the walk around the first turn toward the fabled Twin Spires. Cheers went up at the sight of the horses, and anticipation swelled in the ancient grandstand. Saddled in the paddock and jockeys now onboard, the 13 thoroughbreds returned to the track to the strains of “My Old Kentucky Home” and turned left, jogging toward the starting gate.

The gates sprang open at 5:37, and history was written in real time.

What followed was less than two minutes of unmatched brilliance, which spawned five weeks of awe-inspiring dominance, which birthed half a century of idolatry. An animal became a sports star became an American hero became an enduring icon of untouchable greatness. He was a magazine cover boy, then the subject of books and movies, then ultimately a cultural touchstone.

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

A new display in the Kentucky Derby Museum hails Secretariat as “America’s horse.” At Wagner’s Pharmacy and Diner, across the street from Churchill, Secretariat shirts, hats, coffee mugs, wine glasses and shot glasses are popular sellers— but his ongoing presence goes well beyond local Louisville commerce. ESPN reported in 2020 that there are 263 streets in the United States named after Secretariat. He has inspired statues and murals and the uniform design of the University of Kentucky football and basketball teams. A park bearing his name will open this year in Paris, Ky., near where he spent his post-racing life at Claiborne Farm.

To borrow a phrase William Faulkner wrote for Sports Illustrated from the 1955 Kentucky Derby, Secretariat transformed into the apotheosis of the horse. One can argue it has been downhill ever since for the American thoroughbred.

Fifty years after his Triple Crown, Secretariat still holds the record for the fastest Derby ever run: 1:59 2/5 seconds. He still holds the record for the fastest Preakness run: 1:53 flat (adjusted after a teletimer error originally clocked him in 1:55 2/5). He still holds the record for the fastest Belmont: 2:24 flat.

“One horse holding all three records is insane,” veteran racing journalist Dick Jerardi says. “That can’t happen, but it did. In those five weeks, he ran faster than any horse ever has.”

In direct defiance of a sporting cliché, Secretariat’s records were not made to be broken. They were made to be unassailable. In Derby annals, the only other winner to break two minutes was Monarchos in 2001, on a track surface Jerardi described as “souped-up to the gills that day.” Only in the Preakness has any horse come within half a second of Big Red’s records. In the Belmont, where Secretariat authored the greatest performance in the history of the sport, no other horse has broken 2:26.

Secretariat’s records have provided horse racing such a popular benchmark of excellence that the tracks hosting the Triple Crown probably would like to see them stand forever. “Only if it’s a great horse that broke it,” says Jennie Rees of the Kentucky Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association, noting that Monarchos did not distinguish himself after his 1:59.97 Derby time in 2001, when the track resembled the Bonneville Salt Flats. In terms of managing the speed of the dirt surface, Churchill probably will do whatever it can to avoid producing a fluke Derby record.

(It should be noted that Secretariat’s records in those races are not world records—a 3-year-old horse is not as physically mature as older horses, who tend to hold the fastest marks at longer distances. But they are the standard in the three most famous American races.)

Scientific and medical knowledge have dramatically advanced athletic training—and, subsequently, performance—for humans in recent decades. The amount of information available about thoroughbreds is similarly advanced, but the Triple Crown performance envelope has not been pushed in 50 years.

The time-honored tradition of timed events is that someone or something inevitably comes along that is faster. In human athletic competition, that doesn’t take long.

The oldest swimming world records at Olympic distances are from 2008 for men (Michael Phelps in the 400-meter individual medley) and ’16 for women (Katie Ledecky in the 800 freestyle). The world records in every swimming event from 1973 are laughably slow compared to today’s standards. If a swimming event can be compared to the Derby in terms of a demand on speed and staying power, it’s the 200 individual medley; the world records in the 200 IM have been broken 26 times by the men and 20 times by the women since ’73.

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

In women’s track and field, the oldest record is in the 800 meters from 1983 by Jarmila Kratochvilova—and to say there is controversy attached to that mark from a period of widespread performance-enhancing drug use is an understatement. In men’s track, the oldest timed record is from ’96: Daniel Komen in the 3,000 meters.

The Indianapolis 500 qualifying speed record dates to 1996, when Arie Luyendyk went 236.986 miles per hour. In ’73, the fastest qualifier was Johnny Rutherford at 198.413. By ’84, even the slowest Indy qualifiers were going faster than 200 mph.

Humans are continually figuring out ways to build a faster race car. They have not built a faster race horse. Secretariat very likely would be just as dominant in 2023 as he was in 1973.

Bill Finley wrote last year in the Thoroughbred Daily News about continuing advancements in standardbred times (pacers and trotters), while thoroughbred top-end performance stopped improving around Secretariat’s time: “Based on times for the Kentucky Derby, the Thoroughbred breed did evolve and get faster in the early 1900s. Between 1896, the first year the race was run at 1 1/4 miles, and 1910, the average Derby time was 2:09.8. Over the next 14 years, from 1910 through 1923, the average winning time fell to 2:06.1. By 1962, the record for the Derby had fallen to 2:00.4, the time turned in by Decidedly. Every Derby since 2002 has been run in a slower time. Northern Dancer’s time of 2:00 in 1964 has been eclipsed just twice, by Secretariat and by Monarchos in 2001. If there is a way to produce faster species, no one has figured that out.”

A possible reason why: Winning times aren’t considered vital to assessing the quality (and, ultimately, the monetary worth) of a thoroughbred. Given the differences in racing surface and the day-to-day variables involved in track makeup (namely weather), comparing times is difficult.

Stopwatches aren’t that important on race day. As the old racetrack saying goes, “Time only matters when you’re in jail.”

“While thoroughbred breeders and owners note race times and historical time records, they are not valued above other parameters,” says James MacLeod, professor of veterinary science at the Gluck Equine Research Center at the University of Kentucky. “Look at individual stallion advertisements or the catalog page of a thoroughbred sold at auction. They will list the number of races won by a horse, total money earned and prestigious races won, but only rarely the best time at a given distance. … Owners and trainers of thoroughbreds certainly want to win races, but I have not personally seen evidence that they are highly motivated to set new track records regarding race times.”

MacLeod added that jockeys routinely ease off on a thoroughbred when a race is in hand instead of pushing the horse all the way to the finish line in pursuit of a faster time. With standardbreds, which race at the uniform distance of one mile, times are a “primary performance metric,” MacLeod notes.

Adds MacLeod’s colleague at the Gluck Center, professor Ernest Bailey: “Even though thoroughbred records have fallen at a diminishing rate during the past 60 years, scientists still measured considerable genetic variation for performance in thoroughbred horses. Some suggest that a physical limit is being reached for thoroughbred performance but that the general population may be improving. By that token, Standardbreds may have more room for improvement. Standardbreds are a younger breed.”

Beyond theories about physical limitations, there is no doubt thoroughbreds are trained and campaigned differently today than in Secretariat’s day. With the amount of money to be made in the breeding industry and the increased fragility of the breed, careers are shorter and trainers are more cautious. Top horses are much more lightly raced, and thus far less seasoned, by the time the Triple Crown rolls around in the spring of their 3-year-old season.

Jerry Cooke/Sports Illustrated

The Kentucky Derby was Secretariat’s 13th career race. In the 2023 Derby field of 20 horses, none has raced more than eight times. Secretariat raced nine times as a 2-year-old—he lost his debut on the Fourth of July in 1972, then came back just 11 days later and scored his first win. In the current Derby field, Japanese import Derma Sotogake was the most experienced entering this year, with six races as a 2-year-old.

“If a trainer now ran a horse nine times as a 2-year-old, he’d be fired,” Jerardi says.

A trainer currently in the upper echelon of the sport echoes that sentiment.

“You don’t see [Secretariat’s 2-year-old campaign] anymore,” says Brad Cox, winner of the 2021 Derby by disqualification with Mandaloun. “I think that may have something to do with the breed. If you have a colt you want to win the Kentucky Derby with, why are you running 4 1/2 furlongs in April [at age 2]?”

Several racing insiders interviewed for this story mentioned Flightline, the shooting star of 2022, as perhaps the only horse of the 21st century with talent comparable to Secretariat. But he was a classic example of today’s more conservative approach to training and racing, with just six career races before being retired to stud. Injuries kept him from racing at age 2, and even as a 3-year-old he did not make his debut until late April—far too late to qualify for the Kentucky Derby or be entered in any Triple Crown races. He raced just three times at age 3 and three more at age 4, going undefeated but also largely unnoticed by the general public.

Flightline’s stallion value was estimated by the Daily Racing Form to be $184 million, which is a very good reason he was sent into retirement at the top of his game after dominating the Breeders’ Cup Classic last fall. Secretariat was controversially retired after his 3-year-old campaign because of his value, with his breeding rights sold to a syndicate of buyers for $6 million—a quaint figure today, but a record at the time.

That $6 million price tag added to the pressure on the shoulders of Laurin when he brought Secretariat to Louisville 50 years ago. Revisionist history says that Big Red was a super horse all along, but there were heavy doubts hovering over him during the lead-up to the Kentucky Derby.

For the National Horse of the Year at age 2, the Secretariat hype train slammed to a halt after his shocking third-place finish in the Wood Memorial, his final prep race before the Derby. He was upset by stablemate Angle Light, who finished first, but also by second-place Sham. That was the more significant development, because Sham was an accomplished horse in his own right—and his trainer, Pancho Martin, had been openly feuding with Laurin.

Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated

With Martin trash-talking Laurin for days leading up to the race, Sham became the hot horse in Louisville with the racing press and handicappers. On Derby day, The (Louisville) Courier-Journal listed the picks of 24 national writers—and only two of them picked Secretariat. Eleven picked Sham, with the rest interspersed among other horses. Newsweek’s Pete Axthelm, who would go on to write a cover story for the magazine lionizing Secretariat in June, did not have the colt among his top four Derby picks.

The entire assemblage of 13 Derby horses was disparaged by Jimmy Jones, the trainer of the last Triple Crown winner, in 1948: “Citation would beat any horse in this field 10 straight times pulling a buggy,” he said two days before the race.

After beginning his 3-year-old season touted as the horse to end the 25-year Triple Crown drought since Citation, Secretariat now faced a laundry list of concerns: prominent gambler Jimmy “The Greek” Snyder said the horse was nursing a sore knee; he was suspected of being genetically incapable of going the 1 1/4-mile distance as a son of sire Bold Ruler; or he was simply “over the top,” a racing term for being past his peak.

But the general public remained behind Big Red, who was sent off in a betting entry with stablemate Angle Light as the 3–2 favorites. Sham was the second choice at 5–2. After the starting gate opened at 5:37 p.m. on May 5, 1973, Secretariat began the fastest Kentucky Derby ever by breaking last.

Starting slowly was not unusual for Secretariat, and jockey Ron Turcotte wisely did not force the issue in the early stages. “I just dropped my hand on him and let him run his own race,” Turcotte said. He was still well in arrears of leader Shecky Greene after half a mile, then, in the words of race announcer Chick Anderson, “Secretariat has made a sudden move and is now sixth.”

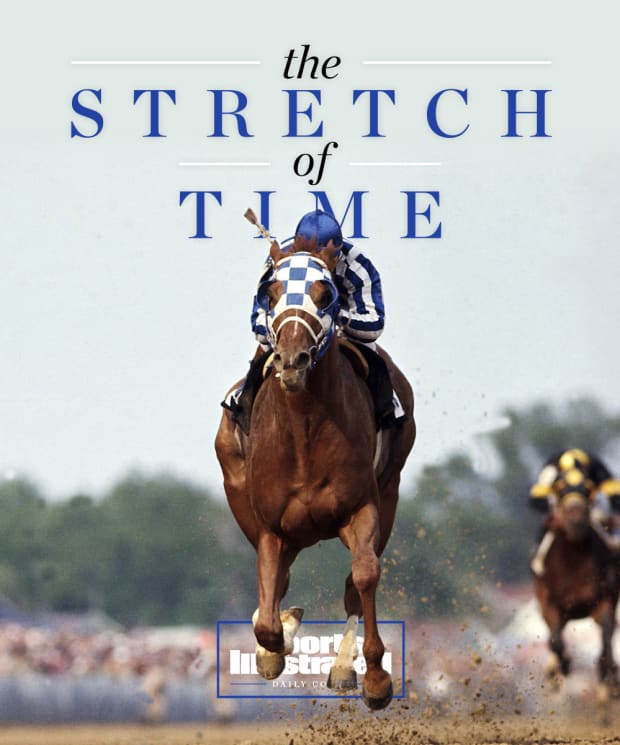

On the far turn, where many winning Derby moves have been launched, Sham took the lead from Shecky Greene. But the chestnut with the blue-and-white checkerboard blinkers was making a powerful drive behind Sham. “Secretariat is fourth on the outside and is now third,” Anderson called, his voice picking up urgency. “And he’s moving at the leaders as they head into the stretch.”

There is no noise in horse racing like the first Saturday in May in Louisville when the Kentucky Derby leaders hit the home stretch. And this particular running was playing out according to the pre-race script: Sham and Secretariat leading the pack, heading toward what appeared to be a tense battle to the wire.

Fifty years ago, Gary Yunt looked down from the Churchill press box at the developing duel. Now 76, he has attended 57 Kentucky Derbies, working many of those as a member of the Churchill Downs notes team. Yunt is a barn-area fixture during morning training hours, bustling from one trainer to the next to jot down workout times on a yellow legal pad, a bush hat pulled down to the top of his glasses and racing coursing through his veins.

In 1973, the Louisville Waggener High School graduate was working for the Lexington Herald-Leader. He had served in the Marine Corps from ’68 to ’72 but managed to make it back home on leave for most of those Derbies. The exception: He listened to the ’71 race on Armed Forces Radio while at Camp Courtney in Okinawa, Japan. Yunt also did a tour of duty in Vietnam before going back to journalism.

Yunt was a Sham man. He liked his horse’s position coming into the stretch, but he saw what was coming behind Sham. He heard Anderson’s call: “Secretariat is in the center of the race track and driving!” And then he felt it.

“I’ve done 57 Derbies,” Yunt says. “That was the only time I felt the building shake.”

The roars kept building as Secretariat unleashed an astonishing closing kick, turning the duel with Sham into a rout. “It’s Secretariat moving away!” Anderson called. “He has it by 2 1/2 [lengths].”

Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated

Legendary New York Times writer Red Smith declared in the next day’s paper, “In 98 years Churchill Downs had never seen such a rush.” He was right. Secretariat covered the final quarter mile in 23 seconds—the fastest Derby run ended with the fastest final quarter in the history of the race. Inconceivably, Big Red ran every quarter mile faster than the previous one: from 25 1/5 seconds to 24, then 23 4⁄5, then 23 2⁄5, and finally 23 flat.

“That does not happen—ever,” Jerardi says. “All horses are decelerating at the end of a 1 1/4-mile race. He was accelerating.”

With doubts trampled and super horse status again conferred, Secretariat turned in two more epic performances that spring. His breathtaking charge on the first turn at the Preakness led to him again putting away Sham by a comfortable margin. And then the Belmont became the stuff of myth and legend, a 31-length victory that even Hollywood failed to sufficiently dramatize in the 2010 movie Secretariat.

Anderson famously declared while calling the Belmont that Secretariat was “moving like a tremendous machine.” In truth, the animal was the perfect racing machine.

He was big—16.2 hands high (a hand is four inches, and a horse is measured to the top of its shoulder), weighing more than 1,150 pounds in April 1973. He was so broad at the chest that he had a custom-made saddle girth that measured 75 inches. His conformation (overall bone and muscle structure) was impeccable. He had a “sloped croup” in the hind quarters, a desirable physical trait in race horses that helps unlock the power in the hind legs. His stride measured nearly 25 feet.

And upon his death in 1989, the final physiological secret to Secretariat was revealed in a necropsy performed by Thomas Swerczek, veterinary researcher at the University of Kentucky. Swerczek, who had done countless equine necropsies in his career, removed Secretariat’s heart and was stunned. He said the organ was roughly twice as large as the average thoroughbred heart.

It was the aha postscript to America’s favorite horse story, one that continues to resonate today.

The number 21 is stenciled on the white wall of Barn 42 at Churchill Downs in green paint. There is nothing remarkable about the stall—no marker denoting it as the temporary home of the most venerated thoroughbred of them all, no sign saying, “Secretariat Slept Here.” It seems like a rare missed promotional angle for the track.

When Secretariat walked out of there on the afternoon of May 5, 1973, he was on his way to profoundly impact American sports and culture. The echo of his thundering hooves still reverberates here, some 50 years later.