Haiti appears to be on the precipice of foreign intervention yet again.

Gangs have been blockading the country’s biggest fuel terminal since mid-September 2022, strangling Haiti’s food and energy supplies. The World Food Program says that Haiti’s need for humanitarian aid is urgent.

The government of Prime Minister Ariel Henry began in early October to call for foreign troops to come help it gain the upper hand against the gangs. The first international response has been a U.N. resolution placing sanctions on the primary gang leader, former police officer Jimmy “Barbecue” Chérizier.

More direct involvement may be on the horizon. The Biden administration has indicated that the U.S. and Mexico plan to submit another proposal for the U.N. Security Council’s consideration that would authorize a “non-UN international security assistance mission” to quell violence and facilitate the distribution of aid.

Conditions in Haiti today are alarming, but as a scholar of 20th-century Haitian history, I am concerned that foreign intervention runs the risk of making a bad situation worse – as has happened repeatedly there for more than 100 years. I believe any response should carefully consider how past aid and military interventions have shaped the dire situation Haitians face today.

US occupation

Foreign influences have long exerted power over Haitian internal affairs.

Initially enslaved in a brutal French sugar colony, Haitians won their freedom and independence in 1804 after 13 years of war and revolution.

But a state of free Black people was viewed suspiciously by the surrounding slave-holding empires in North and South America. There were many efforts to weaken, control or contain the young country.

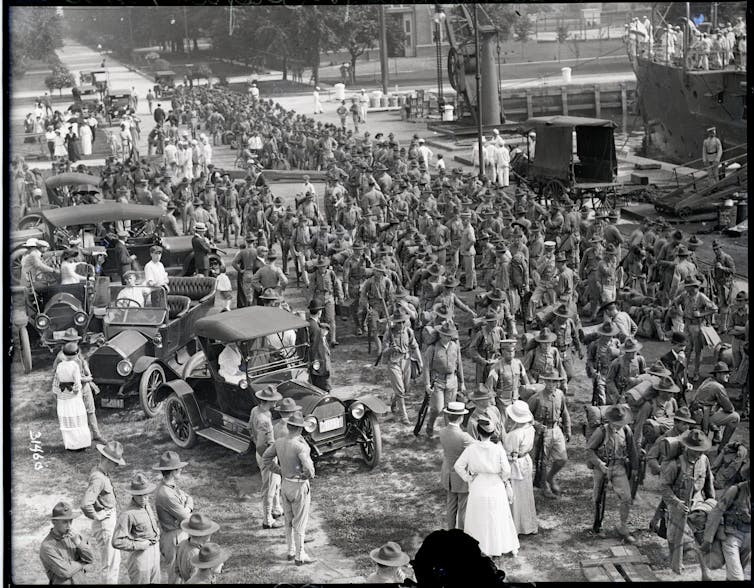

The most expansive of these efforts was the U.S. occupation of Haiti.

In 1915, the U.S. occupied Haiti and ruled it as a client state for 19 years. The pretext for the invasion was to calm political turmoil in Haiti, but scholarship has shown how the U.S. was primarily interested in protecting and expanding its economic interests in the region.

Many white Americans justified the occupation because of their paternalistic ideas about Black people. And many U.S. Marines in Haiti shared a Jim Crow mentality about race, which shaped governing styles and exacerbated tensions between light-skinned and dark-skinned Haitians.

The U.S. military claimed to be a modernizing force in Haiti, but the changes it made weakened the country’s institutions. It undermined Haitian political autonomy by establishing a puppet government that rubber-stamped legislation drafted by U.S. officials.

The U.S. invested heavily in the capital city of Port-au-Prince while letting the rest of the country fall into decline. When U.S. troops departed in 1934, power had been concentrated in the central government, leaving Haiti’s provinces weak and the country with few counterweights to executive authority.

The Duvaliers

This centralized system became a major liability when, in 1957, François Duvalier was elected president of Haiti.

Duvalier, a Black nationalist, found support by mobilizing racial animosities that had been heightened by the U.S. occupation. He had little respect for democratic norms and leaned on a violent paramilitary to crush his opponents.

Within a few years, Duvalier had established a kleptocratic dictatorship that ruled over a major decline of Haiti’s economic and political life. After his death in 1971, his son, Jean-Claude Duvalier, took over as “president-for-life.”

The younger Duvalier, who portrayed himself as a modernizer, enjoyed ever-increasing amounts of support from the international community, especially the United States. But reforms remained superficial and Haiti’s government was still a dictatorship.

In 1986, a popular uprising fueled by grassroots organizing, spiraling economic crises and social discontent pushed the Duvalier family into exile.

Struggles with democracy after dictatorship

Since then, Haitian political life has been a push-and-pull of democratic aspiration and authoritarian repression. In the wake of the dictatorship, Haiti reinvented itself as a constitutional democracy, but the political transition remains incomplete to this day.

Duvalier loyalists and allies in the military violently disrupted the first attempt at an election in 1987. When voting finally took place in 1990, the people elected a left-leaning populist and former Catholic priest, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, in a landslide victory that saw historic levels of voter participation.

But once again, anti-democratic elements in the elite and the military intervened, overthrowing Aristide after just a few months in office and establishing a violent military junta.

President Bill Clinton sent troops back to Haiti in 1994 to push out the junta and reinstall Aristide.

Aristide was overthrown again in 2004, launching new waves of sweeping political violence. A U.S., French and Canadian coalition sent an “interim international force” of troops to restore order and help organize new elections.

They were soon were replaced by a blue-helmeted U.N. peacekeeping mission led by Brazil, known as MINUSTAH. Initially planned as a six-month intervention, those forces remained in Haiti until 2017.

When Port-au-Prince was struck by a devastating earthquake in 2010, MINUSTAH forces were already on the ground. The international community launched a massive, ill-coordinated relief and recovery effort, but, much like the American occupation a century earlier, the primary benefactor was the private sector in the U.S. and other major donor countries.

MINUSTAH’s most enduring legacy was a cholera epidemic caused by poor sanitation practices at a U.N. base in Haiti’s countryside.

The current crisis

MINUSTAH and the Obama State Department oversaw Haiti’s 2010 presidential elections and had a major hand in securing the victory of President Michel Martelly, a pop star-turned-politician who quickly gained a reputation for corruption.

He was succeeded by his chosen successor, Jovenel Moïse, who dissolved parliament in 2020. According to human rights agencies, he worked with local gangs to terrorize his opponents.

Moïse was assassinated in July 2021 – a murder that has yet to be solved. Without a parliament, there is no constitutional line of succession.

Haiti’s government has since lurched forward under the leadership of Henry, an unelected and unpopular official who has been linked to Moïse’s alleged assassins.

Despite these concerns, Henry has enjoyed the backing of the U.S. over his rivals. A coalition of Haitian civil society groups drafted a proposal for a new interim government to take power and organize elections.

But negotiations with Henry’s government have gone nowhere. Given the vacuum of legitimate authority, the gangs Moïse empowered have begun asserting themselves as independent political actors. Chérizier has joined many local leaders in demanding Henry either resign or share power.

Critics are worried that Henry, unrestrained by a democratic mandate or a functioning parliament, plans to use foreign troops to reinforce his political position.

And while past foreign interventions in Haiti have often been launched in the name of stability and democracy, they have not proved capable of providing either.

Claire Antone Payton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.