There’s little else in the food world that brings about as much social turbulence as the durian. This so-called “king of all fruits” is considered a delicacy across its native Southeast Asia, where durian season is currently in full swing.

Global interest in the pungent food has also grown considerably in recent years. But despite this, the durian continues to be loathed as much as it is lauded. What’s behind its polarising nature?

Loved and loathed in equal measure

The international market for durians grew 400% last year. This is mainly due to China, where demand has expanded 12-fold since 2017.

And although heavy rain and heatwaves have resulted in lower yields, the projected growth for 2024 looks promising.

But not everyone is a devotee. The durian often becomes a prickly topic in my conversations with friends in Southeast Asia – with family members clashing over its loud presence in the kitchen.

Durian is even banned in various hotels and public spaces across Southeast Asian countries. In 2018, a load of durian delayed the departure of an Indonesian flight after travellers insisted the stinky cargo be removed.

The fruit’s taste and smell are notoriously difficult to pinpoint. One article touting its benefits describes its odour as a rousing medley of “sulfur, sewage, fruit, honey, and roasted and rotting onions”.

Cultural and historical perspectives

Regardless of its divisive qualities, the durian has a central role in Southeast Asian cuisine and cultures. For centuries, Indigenous peoples across the region have sustainably grown diverse species of the fruit.

At Borobudur, a ninth-century Buddhist temple in Java, Indonesia, relief panels depict durian as a symbol of abundance.

In Malaysia, it’s common to find courtyards full of durian trees in people’s homes. These trees are cherished, as they provide generations of family members with food, medicine and shelter.

The durian also features in creation stories. In one myth from the Philippines, it’s said that a cave-dwelling recluse named Impit Purok concocted a special fruit to help an elderly king attract a bride. But when the king failed to invite him to the wedding party, the furious hermit cursed his creation with a potent stench.

In the West, the durian was first recorded and observed in the early 15th century by Italian merchant and explorer Niccolò de’ Conti. De’ Conti acknowledged the fruit’s esteem throughout the Malay archipelago, but considered its odour nauseating.

Early Western illustrations of the fruit can be found in Dutch spy and cartographer Jan Huygen van Linschoten’s book Itinerario (1596). The author remarks that the durian smells like rotten onions when first opened, but that with time one can acquire a taste for it.

Another scientific account comes from the 1741 book Ambonese Herbal, by German botanist Georg Eberhard Rumphius. Rumphius identified the fruit’s tough outer skin as the source of its pungency, noting how the people of Indonesia’s Ambon Island had a habit of disposing of the noxious rinds on the shoreline.

A fruit of contradictions

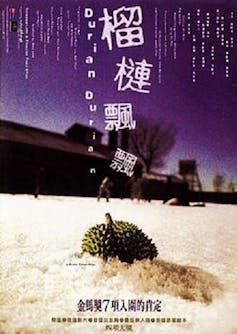

In Southeast Asian film and literature, the durian exerts a powerful yet contradictory effect on the senses. Director Fruit Chan’s film Durian Durian (2000) homes in on these polarising tendencies.

Set in Hong Kong, the film traces the transformation of the characters’ attitudes towards the durian. While the fruit incites revulsion at first, it eventually becomes an object of affection among the family portrayed in the film.

This acceptance of the durian doubles as an analogy, reflecting the family’s acceptance of one of the main characters’ life as a sex worker.

In contrast, the Singaporean film Wet Season (2019) by Anthony Chen highlights various traditional views of the fruit. For example, the illicit affair between a teacher and her student calls attention to a persistent belief in the durian’s ability to arouse sexual desire and boost fertility (although any aphrodisiac benefits remain scientifically unproven).

A number of literary works also probe the durian’s cultural complexity. Singaporean poet Hsien Min Toh’s poem, Durians, opens by referring to the fruit’s “unmistakeable waft: like garbage and onions and liquid petroleum gas all mixed in one”.

At the same time it frames the durian tree as a canny being, as it never allows falling fruit to harm the vulnerable humans spreading its seeds on the ground below.

US poet Sally Wen Mao attends to the enigma in her poem Hurling A Durian. She notes how on one hand the fruit nurtures desire, while on the other it purges memory like a poison. Mesmerised by its perplexing allure, the poet inhales its penetrating scent and strokes its rind until her fingers bleed.

The future and conservation

Although 30 species of durian are known to science (and more continue to be identified), only one species, Durio zibethinus, dominates the global market. Unfortunately, the growing demand for this one type is causing harm by displacing native forests, flora and even Indigenous communities.

In Indonesian Borneo, or Kalimantan, oil palm plantations threaten durian diversity by leaving less room for diverse species of durian to be cultivated. This imperils the cultural practices and beliefs linked to the durian tree.

It also impacts all the other animals that rely on the fruit. Elephants, orangutans and many other endangered fauna relish the durian, while bats and other pollinators help sustain its diversity. As such, effective conservation efforts must engage meaningfully with local people and species.

Perhaps, if past depictions of the durian helped shape its reputation, then new depictions could help conserve this king among fruits.

John Charles Ryan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.