Canada rapidly settled nearly 47,000 Syrians fleeing conflict in 2015 and intends to welcome 40,000 Afghan refugees. Canada has also put no limit on the Ukrainian refugees it will accept.

But let’s not rush to pat ourselves on the back before we take a hard look at our success in supporting refugees after their arrival, specifically in reducing mental health issues like trauma in children.

Education is the most important measure for ongoing integration. My research has argued holistic care is vital for refugee children, and has emphasized the importance of collaboration between health-care workers, government policy-makers, settlement agents, educators, housing specialists, job trainers and others.

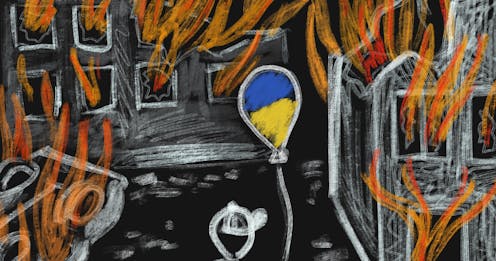

One promising area of research focuses on the role of imaginative play and making art in helping refugee children heal from their traumatic experiences.

Teachers can have impact

Teachers especially can have a significant impact on building refugees’ feelings of safety, trust and sense of belonging. Yet, many teachers still lack professional development for working with refugees, including culturally-sensitive approaches and understanding what basic mental health needs look like in the classroom.

If left untreated, trauma may worsen, limit academic growth and prevent refugees from becoming fully contributing citizens.

Federal research about Syrian government-assisted refugees found that 71 per cent who accessed federally-funded settlement services identified a need for “health, mental health, or well-being support.”

Yet research about refugee Syrian maternal mental health found that concerns about stigma and privacy are major obstacles that prevented pregnant or post-partum women from seeking or accessing mental health services.

Mainstream classroom practices matter

In one research interview I conducted, a teacher relayed that refugee parents did not want their child singled out for instruction or separated from peers to access specialized services.

“Talk therapy” is usually ruled out because children under age 11 have not yet developed the ability to describe complex problems and comprehend their experiences. This is supported by neuroscience which tells us traumatic experiences aren’t in the brain’s rational prefrontal cortex through language, but instead become “stuck” in the amygdala as sensations or fragments. What, then, are options?

Play therapy, art therapy techniques

In play, children act out events they do not understand and explore their emotions, sometimes re-living the unspeakable. Fragments of memories arise and may be re-interpreted, with the child opting to revise for more positive outcomes. This has the potential to reduce trauma.

Read more: Children educate teachers with their testimonies from war zones

Moreover, art works through a pre-verbal, symbolic language that may also release trauma in a slow, natural process. The metaphors and symbols in art may provide access to unacknowledged feelings that can be grasped, which allows change to occur, perhaps even a return to a healthier outlook.

If understanding can be glimpsed through metaphor or symbol, the interior of the person can be given external expression through images in areas where language was silenced, allowing a therapeutic transformation of the self.

Art also helps to develop many academic skills, including critical thinking, problem solving, listening skills, responding to constructive criticism and effective communication.

Many arts activities

Through the lens of therapy, simple art activities in the classroom are already making a difference, such as in these brief examples:

• Visual art: drawing self portraits enhances a child’s self-awareness and starts to shape their new identity; visual journals help refugees communicate with classmates, talk about themselves as they learn English and feel they have friends;

• Dance: using the whole body coordinates senses, breath and movement; movement invites emotional regulation;

• Creative writing/poetry: for students with adequate skills in the language of instruction, teachers might use prompts to suggest parallel experiences; children can re-write more preferable endings to their own stories that reflect their strengths and resilience, and help them move on from tragedies.

Healing narrative, ethical concerns

By adopting aspects of the expressive arts in the classrooms, teachers may help children discover a healing narrative: when the child is ready, they may share their story, discharge psychic energy through self-expression and envision not an ending, but a new, ongoing story.

Refugees who retain a full sense of self are more likely to embrace the future with confidence and feel they belong in an unfamiliar society.

While teachers are not counsellors, and ethically cannot interpret art or ask difficult or pointed questions due to a lack of training, they are nonetheless able to facilitate art explorations.

Safety, belonging

Ethics in teaching overlaps with fundamental art therapy ethics: both professions prioritize doing what is best for the child while staying close to the art process.

Additionally, teachers model ethical and sensitive uses of making art with students when they accept students’ unique responses to using different art forms, allow privacy towards their work and its content and allow students to decide how to participate.

Refugee children who feel safe and believe they belong in the school may gradually disclose what has happened to them, which teachers should accept and support with their empathetic attention and authentic caring.

Susan Barber receives funding from SSHRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.