The UK’s ability to attract business has recently been called into question after its competition regulator blocked tech giant Microsoft from buying gaming firm Activision for US$68.7 billion (£55 billion).

Microsoft’s president not only said this decision was “bad for Britain”, but that the “the European Union is a more attractive place to start a business than the United Kingdom”. A spokesperson for Activision suggested: “The UK is clearly closed for business.”

The UK is not a difficult place to do business, although there are ways it could become more attractive, particularly post-Brexit. As such, there is more to this story than meets the eye.

The decision ties in with wider efforts by UK regulators to examine and adjust such significant deals to prevent them from reducing competition in key industries.

The head of the panel that examined this deal for the Competition & Markets Authority (CMA) said of its decision:

Cloud gaming needs a free, competitive market to drive innovation and choice. That is best achieved by allowing the current competitive dynamics in cloud gaming to continue to do their job.

Regulators are right to be cautious

The UK is the first of three regions to announce a decision on the Microsoft deal – and none of the national regulators involved seem likely to give the green light easily. The US Federal Trade Commission has already launched a legal challenge to block the takeover, while in March, EU regulators delayed their decision until May 22.

Regulators are right to be cautious. They often analyse competition in a sector using measures such as the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI). This calculates the degree of competitive control in an industry by squaring each company’s market share and adding up the results.

A market with an HHI of less than 1,500 is considered a competitive marketplace, 1,500 to 2,500 is moderately concentrated, and over 2,500 is highly concentrated. The maximum 10,000 points denotes a market controlled by a single firm.

The HHI for the cloud gaming sector is already around 3,600, and the CMA says Microsoft accounts for 60-70% of the sector’s global services. So, if the deal went through, the HHI would increase significantly in Microsoft’s favour.

It is the CMA’s responsibility to investigate deals with the potential to affect the competitiveness of UK markets. This is an important role because openness and competition help more firms thrive, boosting innovation and productivity. Consumers also benefit from lower prices and a more comprehensive range of goods and services.

However, putting the breaks on such a high-profile deal will affect how companies and investors view a country’s attitude to business.

How open is the UK?

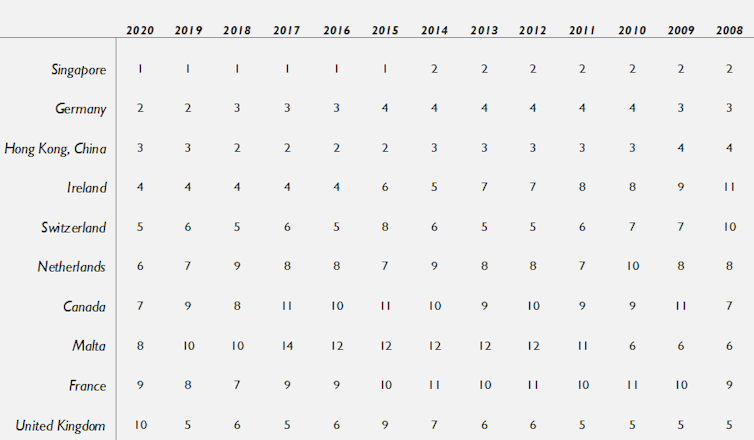

By some measures, the UK is a highly rated investment destination. Other measures tell investors and companies how easy it is to do business in a country. For example, China’s World Openness Index, which measures cross-border economic, social and cultural factors, ranked the UK tenth in 2020 (its latest report) – although this was down from fifth in 2008.

Perceiving countries as ‘open for business’

More recent research from the Resolution Foundation shows UK openness improved relative to France and the US between 2021 and 2022, but the authors added: “We should be cautious in assuming this indicates the UK has become more competitive in recent months despite Brexit.”

So has Brexit damaged the UK’s openness? One argument for remaining in the EU was that membership provided unrestricted access to the European single market, enabling easy movement of goods, services and people across member states.

On the other hand, those wanting to leave the EU argued it stopped Britain from fully capitalising on trade with other major economies such as Japan and the US, or other emerging economies.

I’ve worked with academics at other UK universities to review how UK cities and regions attract investment and talent by using data and technology to create development opportunities and enhance quality of life. According to our review, the UK has a lot going for it in this respect, including an educated workforce, a mature and high-spending consumer market, a business-friendly regulatory and tax environment, and an open, liberal economy.

Brexit could make the UK worse off by increasing red tape for firms that trade with the EU, reducing trade and investment flows. This could increase costs and supply shortages), on top of reducing access to skilled EU workers. But the changing nature of the UK’s post-Brexit economic relations with all economies, not just the EU, is important.

A new global reputation?

The UK’s reputation for openness has clearly been damaged by Brexit. It has led to barriers for UK businesses that trade with the EU, and also for foreign companies that used Britain as a European base.

The country now needs to build a new global reputation, independent of EU membership. A good first step would be to improve perceptions about its openness by pursuing cooperation with the EU, alongside trade opportunities with non-EU countries.

To assist with the latter, the UK can take advantage of its freedom from the EU to enact policies that make it a more attractive place to do business for technology firms than when it was as an EU member. This could include government subsidies and investment to encourage innovation in this sector, as well as ways to help companies address skills shortages.

Firms that do not get their way on deals in the UK’s post-Brexit business environment may try to insinuate that the UK is now less open. But, while being open for business is good for the economy, the CMA is also responsible for considering the interests of British customers, businesses and talent when it makes decisions on deals. This will also help ensure the UK remains a good place to do business.

Tolu Olarewaju does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.