More than three years into the COVID pandemic, both the virus and the measures taken to control its spread have affected people’s lives across the globe. But how can we fully quantify these effects?

While we have estimates of how many people have died from COVID globally (which currently run at just under 7 million), its broader effects – including mental health deterioration due, for example, to the anxiety of getting infected or the isolation of lockdowns – have received less research attention.

In a new study we’ve attempted to quantify how the COVID pandemic has affected global health using an international survey of the general public.

Health economists often quantify health using a metric known as the quality-adjusted life year (QALY). The idea is to assign a value to each year of a person’s life based on their overall health. A person in full health gets a score of one and those who are very ill close to zero.

A common way to measure QALYs is through a brief survey called the EQ-5D, which involves five questions covering key dimensions of health. A person rates their levels of mobility, self care, usual activities, pain and discomfort, and anxiety and depression.

The responses provide a profile of the person’s health-related quality of life, which is summarised by what’s known as the EQ-5D index. When measured at different points in time this can be used to estimate QALYs, which adjust life expectancy to take account of overall health.

For example, a person in relatively poor health may have an EQ-5D index of 0.5 and so they would accumulate one QALY for every two years they live. This technique has been widely used to evaluate the impacts of different diseases and treatments on health.

We measured overall health-related quality of life by including the EQ-5D in a global survey of the public in late 2020, at the end of the first year of the pandemic, just before COVID vaccines started to be distributed. The survey was conducted online on just over 15,000 people in 13 diverse countries.

To ascertain how people thought the pandemic had affected them, we asked them to rate their current health compared with a year before.

Read more: Lockdown, quarantine and self-isolation: how different COVID restrictions affect our mental health

One limitation of our study is that we had to rely on people being able to recall what their health was like prior to the pandemic. While it’s unlikely that a person is able to recall exactly how they would have responded to the survey a year in the past, there is evidence that over and under-estimation errors tend to cancel each other out.

What we found

The pandemic was associated with significantly worse health-related quality of life for more than one-third of respondents. Anxiety and depression was the aspect of health that worsened the most, especially for younger people (aged under 35) and women.

Translating the health reductions into a QALY measure indicated that during the pandemic perceived health was around 8% lower on average.

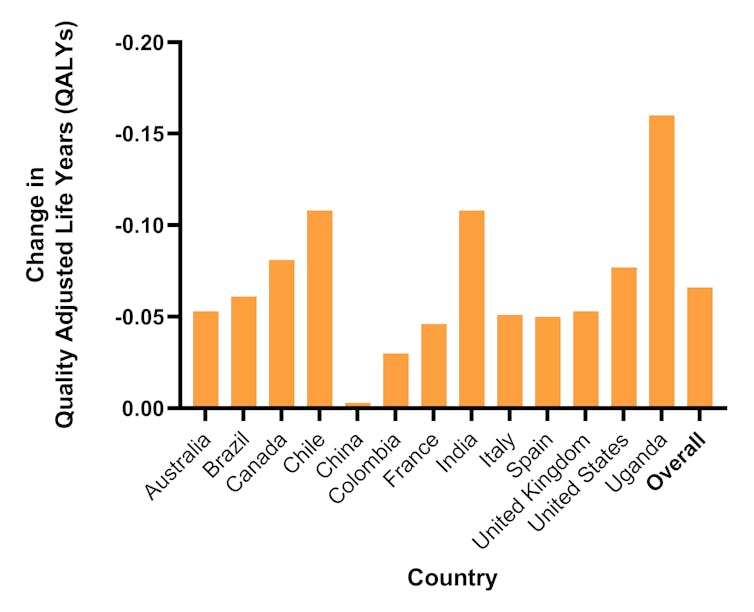

Looking at the results by country, those most affected were middle income countries including India (which had lockdowns for over 40 weeks) and Chile (which had a high rate of COVID infections).

In contrast, participants in China notably reported no significant deterioration in their health status. Although there were lockdowns in China following the emergence of the virus in early 2020, low levels of transmission meant that these were removed within a few weeks.

Mean difference in overall health pre-COVID and in December 2020:

To put the results into context, previous studies have found that each COVID death results in the loss of an average of between three and six QALYs. We combined these estimates with the reported number of deaths in each country to quantify the impact of COVID deaths on overall QALYs in each country.

Based on the reported changes in health in our survey, the loss in QALYs due to the COVID pandemic and lockdowns was between five and 11 times larger than that due to COVID-related deaths. This highlights that only focusing on COVID cases and deaths overlooks the burden of the pandemic and the impacts of policies that are designed to control it.

For example, most countries used some form of lockdowns as a way to contain transmission of the virus, but the ensuing social isolation may have negatively affected the mental health and wellbeing of the population. Similarly, some countries offered economic support to those in financial difficulties, which may have positively impacted their mental wellbeing. QALYs provide a way of quantifying the trade-offs that exist between the positive and negative effects of different strategies.

Lessons for future pandemics

While individual countries have sought to measure the pandemic’s effects on overall wellbeing, the limited number of international studies looking at specific aspects of health, such as mental health, have tended to focus on high income countries. Most global analyses of the effects of the pandemic rely on reported COVID cases and related deaths.

The regular measurement of different aspects of health in a standardised survey enables researchers to start to disentangle the effects of lockdowns and other policies from the impacts of COVID.

Measuring multiple aspects of health through QALYs would also be a useful supplement to existing measures focusing on cases and deaths. This would enable us to look at some of the effects of the COVID pandemic as they’re distributed across the population. For example, while deaths are highest in older people, mental health effects were more prominent in those under 35.

Moving beyond counting deaths to understanding the overall health of the population globally can help us to be better prepared for potential future health shocks.

Philip Clarke receives funding from NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, the NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre, the Health Foundation and the EuroQol Research Foundation. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, or other funding agencies.

Jack Pollard receives funding from the EuroQol Research Foundation. The view expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the EuroQol Research Foundation.

Mara Violato receives funding from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre; the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration Oxford and Thames Valley; the EuroQol Research Foundation. The view expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care or the EuroQol Research Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.