We’ve all seen men lash out angrily when their masculinity is threatened – not least in Hollywood movies. And the extent of such behaviour has also been uncovered in scientific research. But how, when and why does this tendency arise?

A recent psychological study has found that some young boys display feelings of aggression when they feel their masculinity is being challenged. While it is well known that such feelings are present in some adult men, it is not until now that such research has focussed on adolescent boys between the ages of ten and 19.

The study assessed views on masculinity (along with self-reports on the stage of puberty) in more than 200 US boys between the ages of ten and 19. The boys were also asked to take a quiz including stereotypically “male” and “female” questions, such as “Which of these tools is a Phillips-head screwdriver?”. They were then given feedback on whether their score was more masculine or feminine – with the latter being a potential threat to their manhood.

Because it would be unethical to try to deliberately provoke children into aggressive behaviour, the boys were then asked to complete a commonly used cognitive task to measure how aggressive they felt in response to the feedback. This involved completing a series of words. For example, the letters “gu_” could become either “gun” (aggressive) or “gut” (not aggressive).

Many adolescent boys who reported being in mid-to-late puberty (but not before) demonstrated feelings of aggression in response to the perceived threat to their masculinity from the feminine feedback score. But this aggression was more common in the boys who reported external pressure to be seen as masculine, as shown by their agreement with statements such as “I act like a man because I want other people to like me”.

Boys who didn’t feel such external, social pressure, and instead agreed with statements such as “It’s important to me to act like a man”, did not show heightened aggression.

This research raises two important points. First, that boys as young as ten already feel a sense of “manhood” they need to protect. And second, that it’s still common for young people to view masculinity in a traditional way as defined by gender stereotypes, despite all the ways society has changed.

The ‘problem’ with masculinity

Traditional masculinity is only one way of being a man. As far back as the 1970s and 1980s, researchers found that “masculinities” was a considerably better way to refer to men because it highlighted the fact that it is a fluid concept, rather than fixed. Masculinities can and do change throughout time. For example, many men are considerably more involved fathers than those of previous generations.

But the problem with thinking that masculinities are fluid is that it contradicts ideas of patriarchy. Patriarchy is a system by which a small group of men make decisions which affect everyone. Having narrow requirements for how men and women should behave is necessary to maintain control, even though it disadvantages most people.

That’s because wanting to live up to society’s standards of gender can affect how we choose to live our lives – and often in a way that makes us unhappy. Men are famously discouraged from showing emotional vulnerability. They are also at a greater risk of alcoholism and suicide, possibly because they are less likely to learn to deal with their emotions in healthy ways.

But the downsides of patriarchy can also be more subtle and far reaching. For example, men who want to be stay at home dads, or women who want to be police officers, are often ridiculed.

After all, the desire to be accepted and to have the support and approval from peers is particularly important to young men and boys. This appears to be the essence of young men’s desire to act out traditional masculinity – a sense of belonging is absolutely crucial.

The value of traditional masculinity

Why should young boys be so preoccupied with masculinity? And why is the masculinity so bound up with aggressive tendencies? The new research found two main factors to explain this: the external pressure to conform to traditional gender codes, and the desire for the approval of other boys.

Aggression in boys has long been passed off as “biological impulses” – the “boys will be boys” way of thinking. This approach has been criticised for oversimplifying a complex matter which failed to take into account environmental factors, which this current research has addressed.

Also, research of the past has not taken into account the way in which social media replicates traditional masculinity and frames it as cool and desirable. While the new research doesn’t mention them as influences, the media, and increasingly social media, play an enormous role in representing traditional masculinity, including in its most toxic forms.

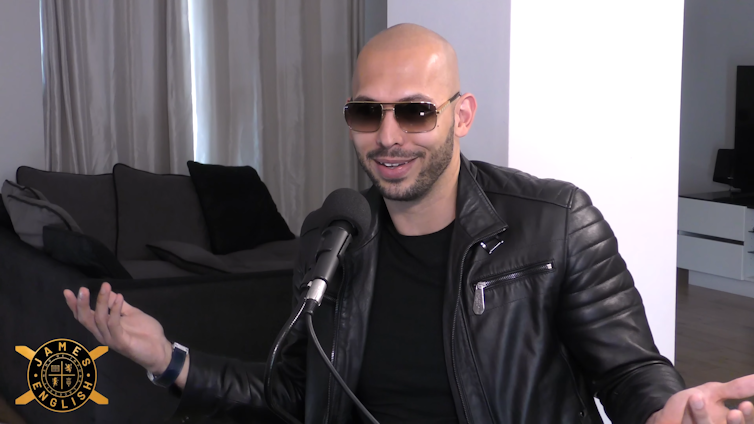

Few had heard of the highly sexist kickboxer Andrew Tate until 2019, when it was reported that he had been arrested for allegations of rape and trafficking. Since this attention, he has become a huge social media personality.

Acts of aggression in response to challenges of masculinity are both decried and supported in society. Sexism, for example, might well be considered wrong, but it is easy to perform and can be almost impossible to challenge. But people like Tate are often celebrated for the sexism and it’s become common for teachers to report seeing his influence on some of their male pupils.

In my research on representations of toxic masculinity in popular culture, I found the way in which men behave in order to garner power and respect is often through domination and oppression. This was underlined by the responses to my research in which male aggression was directed towards me personally

Ways forward

So what can be done about this? Certainly, young people could be educated to not care so much about fixed gender roles. But that is unlikely to succeed, as society is built on binary differences.

A better option may be to educate boys about the many ways of being a man – most of which aren’t based on aggression and dominance. Such educational programmes have already been developed to help promote alternative approaches to masculinity.

Ultimately though, such education needs to be extended to older people. Parental and familial influences regarding gender norms are powerful. Indeed, part of my research is about reminding people that sexism is wrong and that older men, especially, need to act differently if they are to influence the younger generation.

Ashley Morgan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.