Yes, the question is deliberately and mischievously provocative – but a Newsroom survey shows 'Wellington' has become a shorthand for the perception that government is seizing control from local communities

Update: Wayne Brown has won the Auckland mayoralty with a promise to take on Wellington: “Let me be very clear: Wellington’s job is to listen to what Aucklanders say are our priorities, and to fund them – not impose ideological schemes like the $30 billion airport tram, untrammelled housing intensification and Three Waters on a city that doesn’t want them.”

Comment: You can't beat Wellington on a good day, says Paula Muollo. The independent candidate for the city council resorts to the capital's old marketing slogan, as she defends her hometown against the critics.

"Walking around the waterfront on a beautiful sunny day, seeing so many familiar faces along the way on your way to the CBD. You can go from working in the CBD, to lunch on the waterfront, to dinner at one of our many wonderful restaurants, or walk to the stadium to watch a sports game or concert – all in a short distance from our vibrant CBD. Perhaps take in a show. Wellington is a very cultural and artistic city."

Muollo, a real estate agent and former Miss New Zealand runner-up, is seeking to draw a distinction between the city, and the Government and governmental infrastructure based there. "Wellington doesn’t alienate other parts of New Zealand and generally Wellingtonians are very welcoming. We get a bad rep about the weather – they call us windy Wellington."

Wellington's problem (or at least, one of its problems) is that its name has become shorthand for central government decision-making – and a perception that the Government is seizing back control from local communities. This perception has some justification: ministers acknowledge they have embarked on an ambitious programme to turn back some of the devolution of the past 30 years.

Let's call it, mischievously, "revolution".

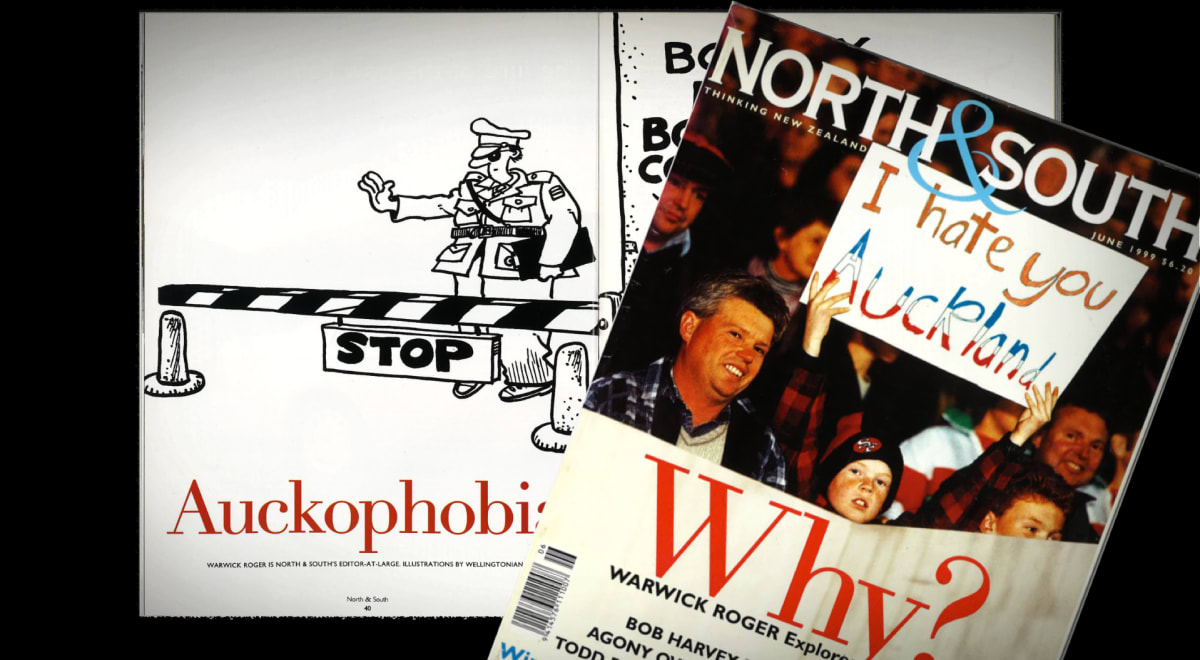

Why does everybody hate Wellington? The question is inspired by a famous Warwick Roger magazine cover in the 1990s, "Why does everybody hate Auckland?"

Back then, Aucklanders were seen as money market wide boys, guzzling champagne at The Viaduct, their BMWs parked outside on the street. Nowadays, the Beemers of popular imagination have been swapped for Maseratis …

Back then, Wellingtonians were seen as civil servants in their walk shorts, spilling out of the city's central railway station on clockwork each morning to populate the grey Stalinist office buildings of The Terrace. Nowadays, they're better-dressed.

A Newsroom survey of mayoral and council candidates, nationwide, reveals a somewhat disturbing disdain for Wellington. Of course, there are the anti-mandate candidates and those who believe the Government is seizing their Three Waters assets.

"We don’t want to be dictated from unelected bureaucrats, especially the ones in Wellington," says Waitematā local board candidate Shayne LaRosa.

"We say NO to Wellington and all of their mandated vanity projects," says Auckland mayoral candidate Pete Marshall.

And there's Ian Brackenbury Channell, the 89-year-old Wizard of Christchurch, who promises to fight "the growing internal imperialism of the national government in Wellington".

"What Auckland needs is a mayor that makes sure Auckland’s voice is heard loud and clear in Wellington." – Efeso Collins, Auckland Council

But there are also mainstream voices who are drawing combative distinctions between their communities and Wellington.

At a Newsroom mayoral debate last month, all four leading contenders – Wayne Brown, Efeso Collins, Craig Lord and the now-departed Viv Beck – criticised the influence of "Wellington".

Efeso Collins reprises this in his response to the Newsroom candidates' survey. "What Auckland needs," the 48-year-old says, "is a mayor that makes sure Auckland’s voice is heard loud and clear in Wellington."

Does it, though? Rather than challenging Wellington, rather than picking fights with Wellington, does Auckland (as with every other city and district) need a mayor who can work collaboratively with central Government?

"I don't think that most of New Zealand understands the scale of Auckland as a super city – it is huge. I don't know that Wellingtonians probably care." – Danielle Grant, Auckland candidate

Outgoing mayor Phil Goff has his detractors, and he too fought with Wellington over reforms like Three Waters – but he also knew how to build consensus and talk constructively. That's a challenge some council candidates are taking on.

Danielle Grant is a local board member seeking election to council on Auckland's North Shore. As a member of the National Party-aligned C&R, she and the Labour Government aren't natural bedfellows.

But she tells Newsroom that Auckland needs leaders who will collaborate for the best outcomes for the super city. "This includes a much healthier relationship with central government, Wellington."

Bottom-up or top-down?

At age 63, Jill Greathead has been a Carterton councillor for more than two decades, and is again seeking election.

"Over the 21 years I have been a councillor I have experienced the bureaucracy serving central Government overwhelming local government with unfunded mandates and treating them like inferior partners."

When Greathead talks of unfunded mandates, she is not talking about vaccine mandates.

She is talking about new directions that take the form of increasing numbers of National Policy Statements, telling councils what ministers require of them. These statements are not voted on by Parliament, but they are underpinned by the Resource Management Act.

According to the Ministry for the Environment, "they provide national direction for matters of national significance relevant to sustainable management". They cover urban development, coastal policy, electricity generation and transmission, freshwater management, and the protection of highly productive farmland. Work is underway on a national policy statement on indigenous biodiversity.

These have changed the way central and local government engage – and Greathead doesn't think it's for the better. "New Zealand needs to run bottom-up – not top-down."

Grant agrees. The 53-year-old councillor says the weight of implementing these National Policy Statements has become overwhelming for a big city such as Auckland. She doesn't think ministers understand the scale of Auckland – councillors get five pages to consider meeting agendas that are sometimes 1000 pages long.

"I don't think that most of New Zealand understands the scale of Auckland as a super city – it is huge. I don't know that Wellingtonians probably care."

And she thinks there's sometimes been a lack of respect between central and local government, that goes both ways.

The Department of Internal Affairs TV adverts, for instance, depicting councils operating polluted water supplies. "I don't think that that's done any good at all. How many places were really turning on sludge out of their taps? It's probably done a lot of damage internationally to the image of New Zealand, on Youtube."

"The Wellington culture that has alienated Kiwis is not geographical in nature, but ideological." – Robert Eady, Far North candidate

Part of the problem in Auckland, she believes, is that the level of engagement between MPs and councillors has diminished. "It used to be that the councillors and the local MPs would all meet on a regular basis, for informal conversations on various different topics, and I think they got to really get a sense of what was important right across all of Auckland. And that has really stopped since Covid.

"I was born in Wellington, went to Wadestown school and Wellington Girls' and Marsden Collegiate. So for myself, when I talk about Wellington, it's definitely shorthand for the difference between central and local government."

Indeed, when pressed, most critics acknowledge they are using "Wellington" as a convenient shorthand for the Government, and the officialdom that underpins it on The Terrace and Molesworth St.

But some argue there is a wider problem – that there is an emerging cultural difference.

"The Wellington culture that has alienated Kiwis is not geographical in nature, but ideological," says 71-year-old Robert Eady, a Sovereign.nz candidate for Far North District Council

Eady is coming from a fringe political position himself (he describes Jacinda Ardern's Government as "tyranny") but is there a grain of truth in the belief that Wellington is ideologically distinct from regional New Zealand?

In our Newsroom survey, 60 percent of mayoral and council candidates identify themselves as economically right-of-centre. We haven't asked the same questions of MPs, but if one assumes that National and ACT MPs identify similarly, that highlights a difference between local candidates and Parliamentarians. National and Act hold 43 of the 120 seats in Parliament – that's 36 percent.

"I don’t blame our central government. Using 'Wellington' pejoratively doesn’t do much other than build an us/them divide." – Stephen Cope, Matamata-Piako candidate

Socially, the candidates are split exactly the opposite way: 60 percent of respondents identify as socially left-of-centre. So any distinction is less clear. In Parliament, many National and ACT MPs would consider themselves to be socially liberal; a few Labour MPs may consider themselves to be somewhat socially conservative.

Council candidates' economic conservatism is reflected in how they say they would vote on managing council money. Despite inflation and population growth affecting councils by increasing their costs, half of respondents would reduce or freeze rates. (Almost as many say they would also vote to increase social spending and infrastructure investment!)

This is, in part, a reflection of how many more local councillors and community board members come from rural and provincial New Zealand. For instance, Chatham Islands has 10 councillors to represent a population of 700; Kaikoura has eight councillors, including the mayor, to represent a population of 4,200. By contrast, Auckland has a mayor, 20 councillors and 149 local board members to represent a population of 1.7 million.

Do the maths: the Chathams have one elected representative for every 70 people; Kaikoura has one for every 525; Auckland has one elected representative for every 10,000 people. That means the balance of local government inevitably tips towards the regions.

That contributes to a disjunction between local and central government.

Are Wellington and the Government the same?

Paul Lambert has some unusual insight: he worked for 10 years for Wellington City Council, before moving to Upper Hutt. He's now seeking his fourth term on Upper Hutt City Council.

Central government has to deal with only one mayor for the big population of Auckland, he points out. A problem for places like Upper Hutt is that the government must deal with eight or nine authorities across Wellington Region – which he says leaves them behind the eight-ball in seeking taxpayer funding.

"It is a hard road to build the relationships when Upper Hutt residents and council will fight hard to avoid a super city imposed like Auckland," he says. "But we need to build regional cooperation for the benefit of all. No point in trying to lure a business to move from one city in our region to another in our region – we want new businesses to start or come to the region. After all, over 50 percent of our workforce commutes out of Upper Hutt."

So his difficulty is more in dealing with Wellington City. He cites the failure of collaborations like Wellington Water or the Wellington Region Amenities Fund, formed with contributions from all Wellington councils to help stop the drift of major events and organisations to Auckland. "It started well but now fallen apart as some cities felt they did not get their slice of cake – if their investment did not make it happen within their boundaries they could not see the benefits if it was happening next door."

"We have the seat of government here in Wellington obviously, but I think that the decision making is balanced for all New Zealand." – Paula Muollo, Wellington candidate

Up in Waikato, 40-year-old Stephen Cope is running for Matamata-Piako Council, a small council that is a member of the anti-reform Communities 4 Local Democracy grouping. But he doesn't think the anti-Wellington, anti-Government rhetoric is healthy. When he's speaking, he does distinguish between local, regional, and central government – but he also specifies who or what he is critiquing.

"I try to identify the specific department where responsibility lies so that I don’t just vaguely blame the powers that be or 'Wellington', but can instead specify that the decision making lies with Manatū Hauora Ministry of Health — as one example from a meeting with constituents.

"I’ve travelled around and seen a few places. I don’t blame our central government. Using 'Wellington' pejoratively doesn’t do much other than build an us/them divide.

"I realise that central government has to balance the needs of five million whereas our district council must only balance 10,000. Of course, the solutions that fit five million are going to be a bit vague and generic, which is also why I support devolving decision-making to regional and district councils and local Māori authorities, as appropriate."

And Wellington? "Nice place. Took the train from Auckland to there. Had to wait a few hours for the ferry to leave. It was nice to walk around and see the art in public spaces. Felt kinda cold and windswept but otherwise with a better appreciation of art than other towns I’ve been in."

Defying dysfunction

Few Wellingtonians would agree their city wields undue influence.

"We have the seat of government here in Wellington obviously, but I think that the decision making is balanced for all New Zealand," Paula Muollo says. "And if anything, I think the consideration of a bigger population like Auckland has an influence on the decision making in general."

The 50-year-old draws a distinction between Wellington, its council, and central government. Indeed, she argues Wellington is short-changed by government. "We don’t seem to get the same government funding for a city that is the capital city, which has been under-funded for decades. [The Government] expects ratepayers to pay for everything which then landlords in turn pass onto the tenants in what is a cost of living crisis."

Muollo concludes: "I don’t think there is any dysfunction in the communication between Wellington and the rest of New Zealand."