January 1952, Bombay. Almost nine lakh residents, braving the cold weather, standing in long queues outside polling stations set up in industrial areas to vote in India’s first general elections. The “harsh climate” of India’s winters necessitated the world’s largest election at that time to be held in 68 phases. Himachal Pradesh headed to polls early, in late 1951, to circumvent the challenges of its inclement weather.

In 2024, the stage is recast. An acute heatwave will prevail over most parts of the country this Lok Sabha election season, the second-longest in history after 1952. The Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) recently announced that above-normal temperatures, and “stronger and longer spells of heatwaves,” are likely to be recorded between April and June, when people are likely to be on the streets partaking in election rallies and campaigns. The 44-day-long electoral exercise could expose people to health hazards, the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) said in a recent advisory to the Election Commission (EC).

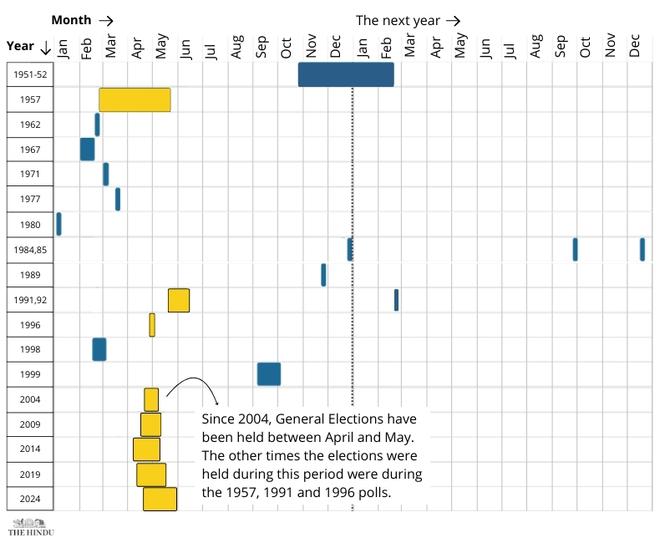

For at least five decades, cold spells, draughty winds or relatively cooler conditions were the setting for India’s Lok Sabha elections. That was until the 2004 General Election, which revised the timeline and temperatures of the national polls.

The 2004 General Election

The polling dates are decided by the EC, set after the dissolution of the previous Lok Sabha. Under Article 83(2) of the Constitution, the elected House of the People “unless sooner dissolved, shall continue for five years from the date appointed for its first meeting and no longer and the expiration of the said period of five years shall operate as a dissolution of the House.” The first elections in 1952 concluded in February, the starting point from which future elections were to be timed.

The first seven election cycles were contained between the months of February and March; a seven-day polling cycle in February 1962; nine days in March 1971; a three day cycle, the shortest-ever, in January 1980.

Exceptions were triggered due to political crises or spells of coalition turbulence at the Centre. The timeline swerved in 1984, after Indira Gandhi’s assassination prompted early elections that year in December. The five-year cycle meant the next General Elections were conducted in November 1989. The first time India voted in the summers, the peak of June, was in 1991. The V.P. Singh-led Janata Party government collapsed, and the new Prime Minister Chandra Shekhar was unable to pass the Budget. The next elections happened subsequently in April 1996, in keeping with the law.

The cycle corrected itself temporarily in 1998, when elections were held three years ahead of schedule after the United Front coalition struggled to stay afloat. Another bout of uncertainty led to the 13th General Elections being conducted in September 1999, when the Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance succumbed to internal schisms.

The next deviation had the most enduring impact. The 14th General Elections were scheduled for October 2004. But these timelines were changed with a political tide that seemed to favour the ruling dispensation. The Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led BJP, emboldened by a booming economy and the prospect of peace with neighbouring Pakistan, decided to dissolve the Parliament and leverage its popularity, calling for early elections in April that year.

The BJP had a successful run in three State elections in December 2003. This came along with a string of economic reforms, a boost in consumer spending and strong monsoons which had provided a welcome relief to a drought-stricken nation. The ‘feel-good’ factor was articulated in the BJP’s “India Shining” campaign, advertised heavily in print and TV. Opinion polls predicted the BJP-led coalition’s resounding victory; Mr. Vajpayee was the preferred PM candidate of choice. “...The ruling NDA “perceives for itself a clear political advantage in holding elections swiftly,” The Hindu’s editorial noted on January 29, 2004. Deputy Prime Minister L.K. Advani told the media next month: ‘’I cannot recall any earlier occasion when I felt so confident about my party’s prospects than this time.”

The 14th General Election were subsequently conducted in four phases, across 21 days, between April and May.

The Shining Campaign famously backfired. The BJP’s tally of seats fell from 182 in 1999 to 138 this time. The 2004 verdict was a “vote against the NDA’s policies,” The Hindu remarked in an editorial. The “divisive policies” pursued in Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh, the aftermath of the Godhra riots and the infamous “India Shining” campaign sullied their reputation. Mr. Vajpayee was reportedly against preponing the polls, his aide Shiv Kumar Pareek told IANS in 2018. “Sarkar toh gayi. Hum haar rahe hain (The government is going. We are losing),” Mr. Vajpayee reportedly said one day. Deputy Prime Minister L.K. Advani and BJP president M. Venkaiah Naidu, however, spurred him on.

Still, the heat generated concerns and necessitated new precautions. The difference in mid-February and mid-summer temperatures during that time could be as much as 12°C. The weather was sultry and the air sticky; the highest temperature recorded in Delhi in May was 46°C. The EC issued directives to States to provide shelter, drinking water facilities, and temporary shades to voters, in addition to raising awareness about heat strokes. Women were asked to avoid bringing children to polling booths; voters were told to carry towels. “In what is equivalent to a war-like situation, the election department is all set to ensure that a para-medical staff officer accompanies every mobile poll party with essential heat stroke medicines and ORS packets,” noted a 2004 Times of India article.

Heat in Lok Sabha polls

The EC decides the exact polling dates and duration based on exam schedules, religious festivals, public holidays, India’s size and varied regional climates. The election cycle spills into June this year due to a six-day delay in the EC’s announcements, along with consecutive festivals such as Holi, Baisakhi and the Tamil New Year (Puthandu).

The last four general elections have been fought under heatwave-like conditions. The India of 2004 is not the same as the India of 2024: heatwaves are becoming more frequent, lasting longer, and becoming more severe. IMD has forecast heat wave spells that could last for 10 to 20 days, instead of the usual two to four day period. More than 10 people died due to the heat while attending a public rally in Maharashtra last April, the biggest ever heat-related death toll from a single event so far.

Voting trends over the years also show a dip in turnout as the mercury levels soar. EC data suggest that in all summer elections —2004, 2009, 2014 and 2019 — the number of voters declined in the later phases of the poll. The voter turnout in the first phase of 2019 elections was 69.5%; it fell to 64.85% in the final phase held in May. The Telegraph in 2009 report attributed low turnout in many parts of West Bengal to high temperatures, which hiked three to seven degrees above normal levels. These statistics, however, hint only at a correlation, and more data is needed to decisively connect the dots between high temperature and low turnout rates.

In April and May, States like Rajasthan, Odisha and Maharashtra, where harsh heatwaves are projected, will head to polls. In the seventh phase on June 1, polling will be held across Bihar, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Chandigarh.

The EC on its part has asked polling booths to maintain “assured minimum facilities,” including drinking water, shelter and keeping oral rehydration salts (ORS) at hand. The NDMA is using television, radio and social media to make people aware of heat-related illnesses. Reports show campaigners, politicians and voters all struggling to deal with rising temperatures. Campaigns are being organised before 11 a.m. or after 4 p.m.; campaigners are advised to wear cotton clothes and cut down on intake of tea and coffee. R. Suresh, a city secretary of the Communist Party of India, told The Hindu recently that meetings are cut short and “long-winded speeches” avoided at rallies.

Once upon a time, “organising elections in summer was unthinkable,” an Election Commission official told The Telegraph in 2009. “But with political instability setting in, the election schedule went haywire. Now we have no option but to hold them as and when they come up.”