National party conventions do not respect deadlines. With their carefully planned spontaneous demonstrations and endless stem-winding speeches, the quadrennial presidential campaign gatherings are famous for running into the wee hours.

Newspapers do not have that luxury. They must hit their deadlines. Particularly for their print editions. The presses are waiting. The trucks, waiting. If thousands of subscribers are to receive their newspapers at dawn, as expected — no, demanded — then those stories better be written on time and edited on time, so the presses can roll. On time.

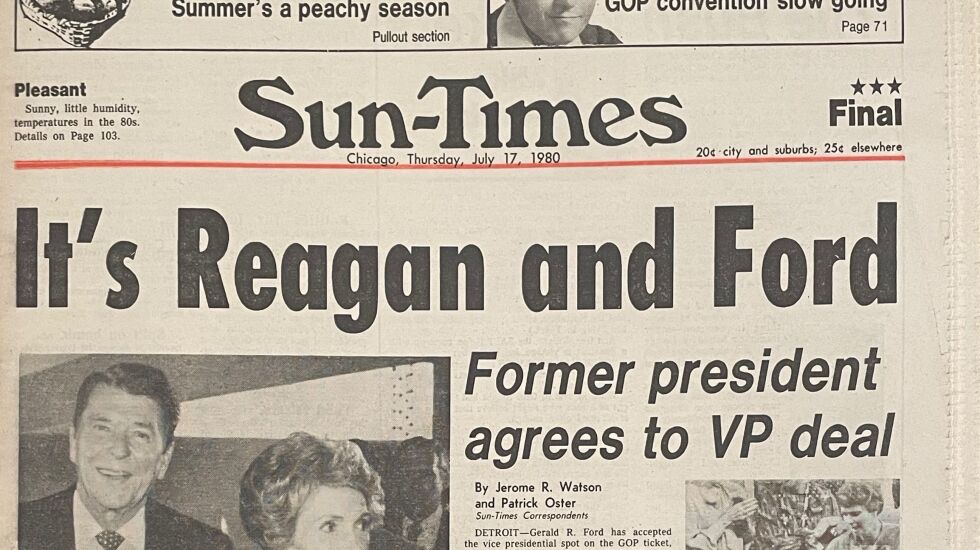

On the evening of July 16, 1980, Republicans at Joe Louis Arena in Detroit argued over who would run as vice president with Ronald Reagan. Jack Kemp? George Bush? Or former President Gerald Ford? It was a choice designed to add political heft to a candidate whom many considered a lightweight, an actor, co-star of “Bedtime for Bonzo.” A consensus built.

“I had guy after guy come up to me and say, ‘It’s all settled. It’s Reagan and Ford,’” recalled the nominee’s brother, Neil Reagan. “It’s signed, sealed and delivered. The governor has left the hotel with Ford.”

Sun-Times reporters on the scene thought official word was coming at any moment.

“People we have every reason to believe would have known,” said Ralph Otwell, the Sun-Times editor at the time. “It was a matter of going with a story a few minutes before it was made official or missing the edition and not getting the news to our home-delivery subscribers.”

A decision was made. The row of mighty Goss presses in the basement of the Sun-Times Building at 401 N. Wabash roared to life, printing out 147,000 issues of the paper’s three-star edition with the headline, “It’s Reagan and Ford.”

Only it wasn’t Reagan and Ford. George H.W. Bush was chosen to run and, eventually, win as Reagan’s vice president. An instant collector’s item was created, though without a gleeful president holding it up, the way Harry Truman displayed the Tribune’s notorious “DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN,” the Sun-Times gaffe didn’t become nearly as famous. Gerald Ford did frame a copy on his study wall.

We regret — and admit — our errors

To write is to err. Every newspaper in existence has a “corrections” column published as needed, listing mistakes that need to be rectified. Misspelled names. Wrong titles. Errors of fact.

For all the “fake news” grief the media has been given in recent years, public expectation is still strong that newspapers print the truth. And they must do a pretty good job of it, because the times they get the news wrong have a way of lingering.

As the Sun-Times marks its 75th anniversary, it would be a departure from our habitual frankness to hit the highlights but ignore the times we fell short. Sometimes spectacularly short. The paper certainly didn’t divert its gaze after the “It’s Reagan and Ford” blunder, running a story the very next day, explaining what happened. That’s how we’ve always rolled.

“Everyone makes mistakes,” said Don Hayner, a former Sun-Times editor in chief. “The sin is covering it up. That is antithetical to our business, to our being. Our ethos demands, or should demand, telling on ourselves when we screw up.”

In the spirit of telling on oneself, and since I reached out to colleagues to discuss their mistakes and was gratified by their openness, I should go first.

In some ways, the internet age has been a boon to accuracy. Readers can serve as a kind of rump copy desk, pointing out errors that can be immediately corrected. But online editing can also remove layers of protection. Speed and accuracy are not friends.

Mistakes spread faster on the internet

For instance. there was my killing Karen Lewis in 2021.

OK, I did not actually kill the president of the Chicago Teachers Union — she died of brain cancer. What I did was prematurely publish her obituary in 2021, a major bungle at any paper.

It was an innocent mistake. A literal slip. Early one Sunday morning I sent in my column, then called up her obituary — we prepare these in advance, to write them carefully and avoid having to scramble. I would check on her obit from time to time to give it a polish.

As I read, I rested my hand on the computer mouse a tad too heavily when the cursor was over the “Publish” button. There was a click. To my horror, the story went up, on the top of our website.

Having never published anything before — or since, it’s not my job — I didn’t know how to get it down. A frantic call to the city desk. Clawing the story back took, oh, 10 minutes, and by that time the story was radiating out over social media.

Other news organizations couldn’t resist the fun of tweaking us over it — both the Tribune and local TV news did something. The publisher at the time, Edwin Eisendrath, insisted I phone Lewis and apologize, which I did, taking the opportunity to read her her obituary, since it was now public anyway. Fortunately, it began, “Karen Lewis was fearless ...” She was also gracious, good-humored and forgiving.

That episode is a reminder that blunders usually impact the blunderer more than anybody else. Only a few people actually saw the front page of the Sun-Times in 1996 announcing the death of Chicago’s Joseph Cardinal Bernardin that misspelled the beloved cleric’s name — but one of those was executive news editor Joyce Winnecke, who saw the mistake, which she suspects she herself may have also committed. Leading to the rare experience of flying downstairs into the pressroom and shouting that classic line, “Stop the presses!!!”

Though perhaps with a bit more desperation than in the movies.

Columnist snared by someone else’s snafu

Any piece of writing appearing in a newspaper has many hands involved in its creation, and one of the most frustrating moments in this profession is when somebody else’s snafu makes you look bad.

In 1987, media critic Robert Feder’s “bug” — his byline photo — and name were placed atop a Judy Markey column celebrating Annette Funicello, the curvy Mouseketeer on the 1950s TV hit “Mickey Mouse Club,” and envying her, umm, breasts.

“But what we could not live with was the inordinate discrepancy between the way Annette looked in her T-shirt and the way we looked in ours,” the Sun-Times straight-laced media critic seemed to be confessing.

Although no one ever ’fessed up to the mistake, Feder believes it was a simple error and not a prank.

“I remember being mortified at the time,” recalls Feder, who declined to show up at the office the next day, “out of a combination of anger and humiliation.”

Asked what he considers his biggest blunder, Feder cited the contemptuous reception he gave to Tom Joyner,the “fly jock” who in the mid-1980s contrived to host a radio show in Dallas in the mornings, then fly to Chicago, where he deejayed an afternoon show.

“Whether Joyner lasts through all five years of his contract or collapses after the first week of his idiotic scheme really doesn’t matter,” wrote Feder. “ The only thing that counts is that Joyner has transformed himself into a human publicity stunt.”

The supposed stunt lasted eight years, and the future Radio Hall of Famer became the only DJ to simultaneously host two different top-rated shows in two major markets.

Even Roger Ebert got it wrong

Then again, even the greatest critics unleash opinion that time proves unwise. Roger Ebert was the first movie critic to win the Pulitzer Prize. He also wrote this about “The Graduate,” released in 1967, directed by Mike Nichols:

“His only flaw, I believe, is the introduction of limp, wordy Simon and Garfunkel songs and arty camera work to suggest the passage of time between major scenes,” Ebert wrote, regarding classics like “The Sounds of Silence” and “Mrs. Robinson.”

Thirty years later, Ebert reconsidered that opinion.

“When the movie was first released, I wrote of the “instantly forgettable’’ songs by Simon and Garfunkel,” Ebert wrote in 1997. “History has proven me wrong.”

We haven’t even touched upon the realm of malpractice, which is worse than mere blundering. In 1995, the editorial page editor, Mark Hornung, resigned after being caught plagiarizing an editorial from the Washington Post.

Years earlier, Wade Roberts, a newly hired sports columnist, invented a bar in Eden, Texas, and populated it with a colorful cast of imaginary local residents. The story struck columnist Mike Royko, who by then had moved from the Sun-Times to the Tribune, as too good to be true, and some digging proved it indeed wasn’t true.

Roberts, for what it’s worth, always insisted the bar was there, and he and managing editor Ken Towers went back to Eden and spent two days fruitlessly trying to find it. Several other critics have gotten in hot water for describing things that didn’t happen — outfits not worn, songs not sung — in shows they were supposedly reviewing in person.

Some mistakes are open to interpretation. In 1990, pitcher Danny Jackson was signed by the Cubs. His previous teammates nicknamed him “Jason,” like the killer in the “Friday the 13th” movies. The sports desk thought it would be fun to superimpose a Jason mask over Jackson’s photo, and deputy managing editor for sports Alan Henry approved it. Clever illustration? Or unacceptable fabrication? Editor Dennis Britton obviously thought the latter; he fired Henry.

Raccoon story leads to boycott call

Deceit is far more rare than simple error, though sometimes innocent mistakes can have big repercussions, in the newsroom and the city at large. There was a 1992 feature that came to be known among the paper’s staff, notoriously, as “the raccoon story.”

One of the paper’s sharpest writers, Tom McNamee, was charged with writing something about the problem of raccoons in the suburbs. That’s the type of basic story that can be jazzed up, and McNamee struck upon a trope, dubbing raccoons “the gangbangers of the animal world” in a protracted metaphor that mentioned police, single moms and metal detectors.

Do you see the problem in that? Some did, some didn’t. The Tribune’s Eric Zorn explained it this way:

“A number of readers and members of all factions of the Chicago City Council made a link between the word raccoon and [a] racial epithet ... and took references to street gangs and disadvantaged people as thinly disguised allusions to black people.”

Ald. Allan Streeter (17th) called for a boycott of the Sun-Times. The City Council’s human relations committee scheduled a hearing. Even Mayor Richard M. Daley piled on. Operation PUSH asked to meet with the publisher. Talk radio lit up — some condemning the story, others denouncing “political correctness.”

McNamee apologized. Employees were all given sensitivity training. Time reduces the sting, somewhat.

“It is still a sensitive topic for me,” McNamee said recently. “If Don Hayner had not given me great advice at that time — don’t do anything rash, this too shall pass — I might have quit. It’s not great to have the mayor and City Council declaring you’re a racist, especially when you’ve grown up in Chicago in a particularly racially charged environment on the Southwest Side and spent your young life trying to be a better man than all that.”

McNamee eloquently encapsulated why mistakes should not be buried but examined.

“I learned from this, though,” he said. “I learned I had a cultural blind spot. It never occurred to me how others might read that silly column, how they might hear a dog whistle that was not there — and the only cure is to listen to others (others of good will) and be open to it. I have always thought it later made me a better editorial page editor; I loved and felt secure in the racial and ethnic diversity of our board, having learned the hard way that we all made each other better — and saved each other’s ass. The experience made me a little bit quicker to stand up for others who, in my view, were being labeled and judged unfairly.”

No more room for errors

Of course I couldn’t include them all, from the Sun-Times repackaging essays of Pope John Paul II and pretending they were columns written especially for the paper, until the Vatican demanded we stop, to Wally the Wall-eyed Pike, a cartoon fish that was to direct readers to highlights in that day’s paper.

Send in your nominations, and I may collect them in a future column. (And yes, by all means, suggest “giving you a column in the first place, Steinberg” as the biggest blunder the paper ever committed. Though you’ll have to get in line.)