Texas is known for fiercely promoting its oil and gas industries, but it’s also the No. 2 renewable energy producer in the country after California. In fact, more than a quarter of all the wind power produced in the United States in 2021 was generated in Texas.

These projects benefit from a lucrative state tax incentive program called Chapter 313. That incentive program expires on Dec. 31, 2022, and the rush of applications for wind and solar energy projects to secure incentives before the deadline is providing a rare window into a notoriously opaque industry.

By reviewing the applications and ownership documents, we were able to track who actually builds and owns a large portion of the nation’s renewable energy, when and how those assets change hands, and who ultimately benefits from the tax incentives.

The results might surprise you. The majority of utility-scale solar and wind energy projects in Texas aren’t owned by companies focused on renewable energy – they’re owned by energy companies or utilities that are better known for fossil fuels, including some that have aggressively opposed renewable energy and climate policies in other states and nationally.

The policy implications of these findings are complex. While these subsidies might lead some energy companies to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, they also can allow energy companies to continue polluting from existing fossil fuel assets while collecting the subsidy benefits.

A subsidy program that saves companies billions

Chapter 313 limits how much companies have to pay in property taxes for schools if those companies build infrastructure and agree to create jobs. The Texas Legislature passed it in 2001 when a number of large companies, including Intel and Boeing, were considering Texas for an investment location.

Companies using this program can save billions of dollars in local property taxes. However, investigations have revealed high costs per job and minimal requirements for companies. The state’s school funding system also suffered.

The program wasn’t renewed, but companies that applied for the incentive by Aug. 1, 2022, could grandfather in their investments for 10 years of tax benefits. That led to the rush of applications, including for wind and solar projects.

Who’s proposing renewable energy projects?

We reviewed 191 wind and solar project applications filed in 2022. If built, these projects would almost double the number of renewable energy projects in Texas.

It is notoriously difficult to track the owners of renewable energy projects in the U.S., because most are structured as limited liability companies, or LLCs. However, the application for Texas incentives requires not only information on the owner, but also a signature of an individual representative of the owners. That provides a glimpse into the impact that subsidies can have and who benefits.

We found that just over a third – 69 out of 191 proposed projects – are owned by renewable energy companies, such as Danish company Ørsted and Recurrent Energy, owned by Canadian Solar.

Over half the proposals – 101 – were submitted by energy companies known more for oil and gas, or utilities with fossil fuel assets. This includes the renewable energy subsidiaries of oil supermajors such as Total and BP, and utility owners including EDF, AES and Engie, all of which are major global players.

Some project applications came from investment groups such as DeShaw Group, Cardinal Investment Group and Horus Capital. Apex Clean Energy, a renewable energy subsidiary of the major investment manager Ares Management, frequently showed up in applications.

New owners take over

The proposed projects provide a snapshot of the renewable energy projects’ developers – but what happens after these projects are built?

To figure that out, we also looked at all renewable energy projects completed in 2020 and 2021 that participated in the Chapter 313 incentive program.

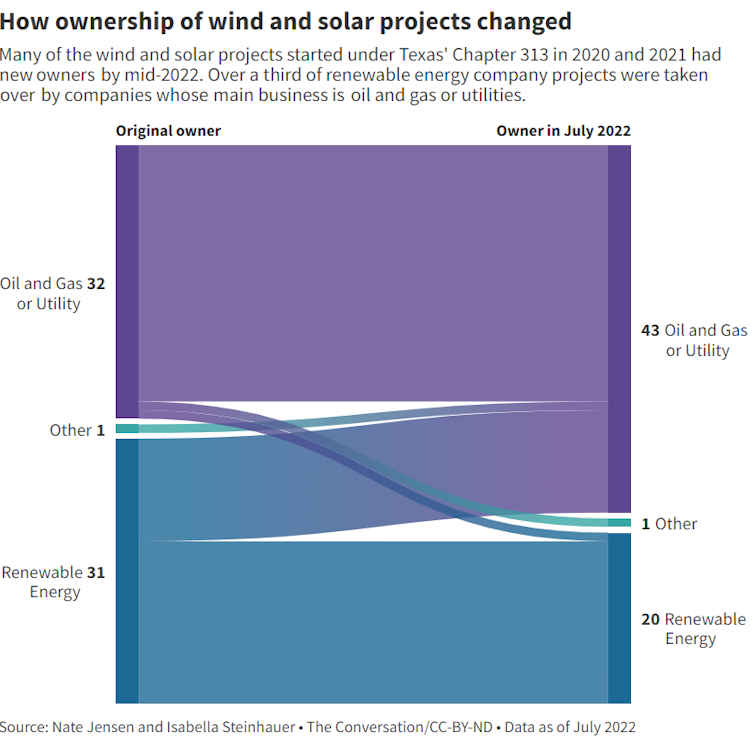

To our surprise, almost half of the projects built in 2020 or 2021 had changed hands by 2022. Some were due to company acquisitions. Many other projects were sold.

This changed the composition of owners. While renewable energy companies owned roughly half the projects at the application stage, by 2022, two-thirds of the projects were owned by utilities and energy companies with fossil fuel assets.

The original developers may have benefited from the first year or so of the tax break, but the new owners are poised to reap the majority of the remaining years of the 10-year property tax incentive.

The most common pattern of sales was a renewable energy developer selling a project to an energy company or utility. For example, Duke Energy purchased a solar project originally owned by Recurrent Energy, and Alpin Sun sold a solar project to BP.

We found that ownership by self-described “venture capitalists” and other investors was rare before 2022. The lucrative and expiring incentive program likely led to a gold rush of applications, including by some companies with limited experience in renewable energy.

When renewable incentives become subsidies to fossil fuel companies

Many of the owners benefiting from these subsidies have parent companies with high carbon emissions and a history of fighting climate policies.

For example, the company with the most renewable energy projects subsidized under Chapter 313 from 2020 to 2022 is NextEra. NextEra is also the parent company of Florida Power and Light, a utility that has campaigned against rooftop solar in Florida and sued to block hydropower imports in Massachusetts. In Texas, however, NextEra lobbied for a continuation of Chapter 313 incentives.

Other major energy companies in the owner list include France’s Total Energy, BP, Duke Energy and Savion, which is owned by Shell.

The data suggests some possible tensions within green energy policy.

Environmentalists have long argued for federal and state subsidies for renewable energy as a means of combating climate change, including in the climate- and inflation-focused bill currently in Congress.

However, as our data analysis shows, the owners who benefit from renewable energy incentives can in some cases be the same fossil fuel companies that actively oppose a green energy transition. The results of a 2021 study, using data released by energy companies on earnings calls, also suggest that energy company investments in renewable energy projects are often simply diversification strategies – they aren’t replacing fossil fuels.

Our analysis is based on one program in Texas, but with the size of the Texas renewable energy sector, and the companies involved, it can offer insights for broader renewable energy policies.

Key to any subsidy program is clearly articulating the goals and tracking success in meeting them. If the goal is to reduce greenhouse as emissions, that means examining who is benefiting and determining if the subsidies are actually leading to a transition away from fossil fuels.

Our data begins to shine a light on the answer.

Nathan Jensen previously received funding from John and Laura Arnold Foundation for peer-reviewed research on the Texas Chapter 313 Program.

Isabella Steinhauer does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.