PLACE names are often indicators of what you can see at a location. But not always. For example, Whitebridge.

Approaching the suburb on the ride up the hill along the Fernleigh Track, I cycle under a ... grey bridge.

It is one of those monotonous pieces of infrastructure, just doing its job, carrying vehicles on Dudley Road over the old railway cutting.

From the late 1800s to 1970, there was an actual white bridge here. But age had its way with the timber on the bridge, and the concrete replacement was built.

Another local place name provides a clue to this location's past, when it was the rail line from Adamstown to Belmont.

Near the top of the hill, opposite the former Whitebridge station platform, is a residential development called Fettlers. That name refers to the gangs of labourers who maintained and repaired the line. As rail historian and author Ed Tonks points out, there is still a fettler's shed squatting by the track near the former station.

In a number of sections along the Fernleigh Track, including on the run up to Whitebridge, there are other rough-hewn reminders of those who toiled along the rail line.

They are the cuttings and embankments carved into the terrain, taming it a little, in order to make the line more manageable for trains and their crews. Which means all that hard work in the past has made the track less torturous for cyclists and joggers.

So each and every time we cycle or run through the clefts in the landscape, we should say "thanks" to those rail workers.

Ed Tonks says the cuttings were "made from black powder, blood, sweat and tears".

The southern approach to Whitebridge was going to be a tunnel, not a cutting, through the rock.

"Initially there was going to be three tunnels [along the Belmont Line] but there ended up being one," Ed Tonks says, explaining the builders opted for cuttings, as they were cheaper and the planned route had been altered slightly.

While much has changed through the years, as the working rail line has been transformed into a recreational path, what has remained constant is the need for maintenance along the corridor.

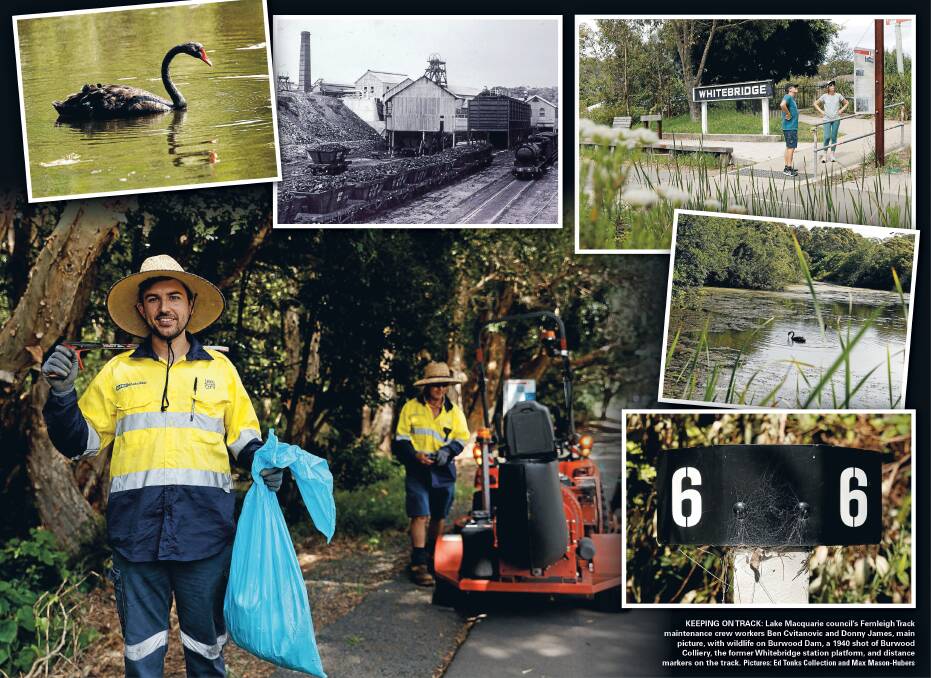

The fettlers with picks and shovels have been replaced by teams in high-visibility shirts and steering tractors with turbine blowers attached, clearing debris off the track.

For as long as the Fernleigh Track has been here, so has Donny James.

Donny is the supervisor of Lake Macquarie City Council's Fernleigh Track maintenance crew. He has worked on the track since the final stage opened in 2011.

The crew works on the track two days a week; on Mondays, cleaning up after the weekend, when usage is at its greatest, and on Fridays, preparing for the weekend.

The workers take care of 13.9 kilometres, from Belmont to just south of the tunnel at Adamstown Heights. North of there, through to Adamstown, the track is maintained by crews from the City of Newcastle, which owns that section.

"We try and get the whole track done in a day," explains Donny.

On this day, he is joined by Ben Cvitanovic, who has worked on the track for about two years.

A horticulturalist, Ben sees the world around here through green-coloured glasses, charting the track by its vegetation.

"The terrain changes as you go along, from the swampy area around Belmont to the rainforest at Burwood," he says.

Both workers have noted the numbers of track users have soared since COVID took hold.

Donny estimates numbers have quadrupled. What has also increased are the compliments from users, appreciative that they have somewhere accessible to escape from the cares of the world.

As Donny is explaining this, an older bloke cycling past yells out, "Doing a great job, fellas!"

The crew has come to know the regulars on the track, and not just the humans. For a time, there was a red-bellied black snake in residence near the Belmont end, but Donny hasn't seen it for a while.

Both crew members use the track for recreation as well, but, when he is out riding, Donny James finds it hard to leave behind work: "I look at things, and think, 'I'll fix that next week'."

Asked what he likes most about his job, Donny smiles and replies, "Listen".

The air is filled with birdsong and the soft breath of a breeze through the trees.

"For us, it's not just our job, it's our passion. We like it to look good."

The council crews have help in keeping the Fernleigh Track looking good.

Along its 15 or so kilometres are residents and community groups who volunteer their time and lend a hand in so many ways, from removing weeds to planting native vegetation. And more are taking up the cudgels, or pruning shears, at least, to protect and beautify the track.

This month, the Fernleigh Track Whitebridge Landcare group comes into being. The resident behind the group is Jenny McGavin.

While she has lived in Whitebridge for about 10 years, it was the COVID restrictions compelling Jenny to stay close to home to exercise that opened her eyes to the Fernleigh Track.

"You don't appreciate your own backyard until you're made to appreciate it," she says. "I was really surprised. It's such a beautiful spot, and we're so lucky to have that resource."

Having seen areas that needed weeding as she walked along the track, Jenny McGavin thought it would be good to start a group to take care of the land near Whitebridge.

"So I thought, 'Why not me?'," she says.

The new Landcare group plans to take care of a stretch from just north of Whitebridge to Burwood Road, and Jenny McGavin hopes volunteer numbers will grow just as interest in the track itself has.

"You could see how super busy it was during the lockdown," she says. "If they're using it, and they see people working on it, I'm hoping that will entice others to join in and be active."

Near where the track begins to head down the hill sits the former Whitebridge station platform.

When I go past, there are people sitting on a bench, as if waiting for a train. But now the only thing you're waiting for is your breath to catch up after the ascent. The passenger service stopped in 1971, with the platform having been used since 1917.

At this point, I'm more than halfway along the track, with about 5.5 kilometres to ride to Adamstown. I passed the halfway mark coming up the hill from Redhead. Track users have an idea of how far they have come, and how far they have to go, thanks to another artefact of the rail era.

Track side posts note each kilometre, and there are even half-kilometre signs.

Ed Tonks explains these posts were marking the distance from the junction with the main government-owned line at Adamstown.

"These distances were important for fettlers or if there were accidents along the track," he says.

A gully straggles down the slope between the track's right side and a string of backyards. There is a turn-off that leads into a housing development, Dudley Beach Estate.

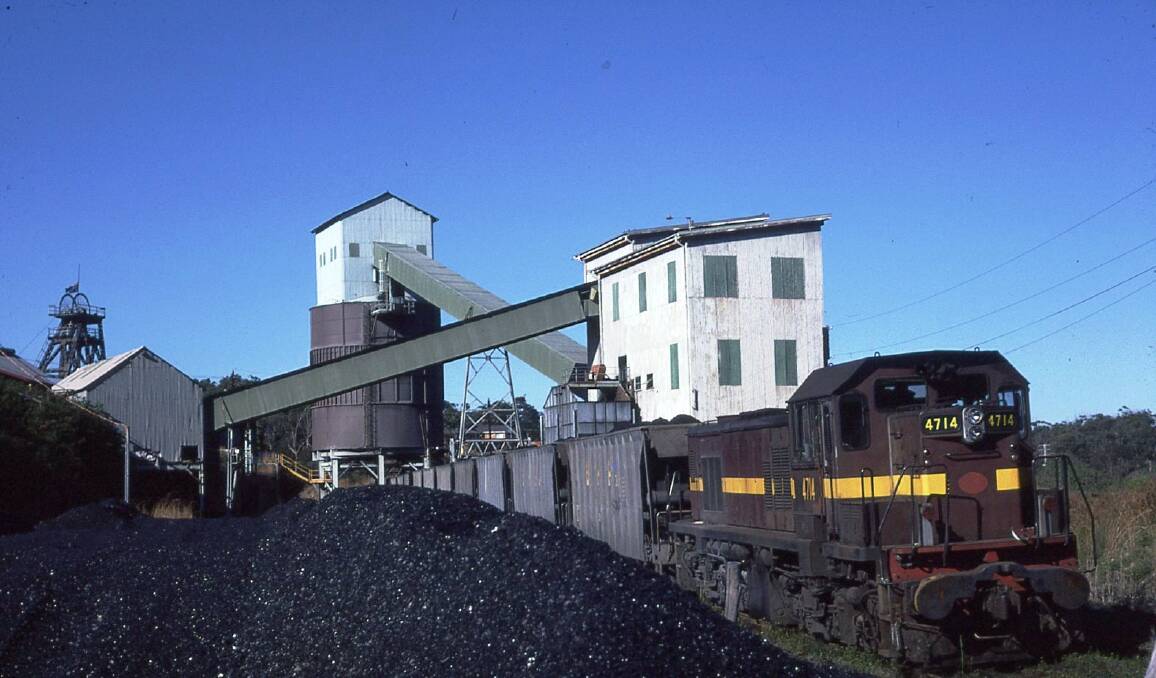

The name references the grand stretch of coastline just a little to the east, and that many of the fine houses with big windows are craning to get a view of. But it could have been called Burwood Colliery Estate. For these houses rise from land that was a mine for the best part of a century.

The Burwood Coal Company began sinking what was called the No.3 shaft here in the late 1880s.

There had been two other shafts under the Burwood name sunk earlier on the shores of Glenrock Lagoon. But the focus shifted up the hill to the No.3 shaft, and to the nearby railway for transporting coal, and the operation was known as Burwood Colliery.

The mine reached deep into not just the earth but also the lives around it. Little coastal communities such as nearby Dudley may have been salt-scented but they were coal-powered. The mine helped fuel the economies and set the clock for those communities.

Each day at 6.50am, the colliery's whistle would sing across the coastal heathlands and valleys. It would sing just as the miners' train arrived, bringing workers from Newcastle suburbs further afield.

The trains also transported those working at nearby operations, such as Dudley Colliery, located a little further down a branch line. What brought the miners in could also take residents out, as the trains came to be used for a general passenger service as well.

In the earth under Whitebridge and Dudley, livelihoods were created but lives were also lost. In 1898, 15 men were killed in an explosion at Dudley Colliery. In 1901, three men died in an explosion at Burwood. They were among 48 workers killed at Burwood during the colliery's operational life.

By the late 1930s, the Dudley colliery was gone, and the branch line was closed. But the trains kept trundling to and from Burwood, and, after BHP had bought the colliery in 1932, coal-filled wagons headed for the steelworks.

Tattooed into the ground along the track is a souvenir of the rail days, with a stretch of old lines. Slowly rotting sleepers are submerged under gravel, peeking through in places. The rail lines now serve as track borders, and they lead, as they once did, to the Dudley Junction signal box. Or, at least, what is left of it.

The former signal box is nothing but a surreal pile of buckled iron sheets and timber. The destroyed building is hardly the only change around here.

Historical photos show how industry ruled the landscape, including one image of the colliery's mainframe dominating the scene. The colliery hasn't been pushing the bush out of the way for many years, so there is once more a tangle of trees, with a hint of the big homes, to the east. .

The last coal train pulled out of Burwood Colliery in October 1982, and the demolition of its buildings began the following year. Among the few reminders of those days is the old bowling club building across the road from where the colliery once stood.

Just off the western shoulder of the Fernleigh Track is another legacy of mining: the colliery dam, with the concrete wall holding the water back. The waterway that was dammed looks spindly as it picks its way through the bush, and it has a name that sounds lean as well: Tin Hare Creek.

It was named after the railmotors that scooted along the tracks here in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The passenger trains were referred to as "tin hares", because their movement was apparently reminiscent of the mechanical hares used in greyhound races.

The little creek provided enough water to create quite a reservoir for the mine's use. When the colliery closed, the Burwood Dam became clogged with reeds. But the waterway was cleaned up, and it attracts bird life.

Fernleigh Track heads down the hill, chasing Tin Hare Creek through the bush. That watercourse flows into Flaggy Creek, which, in the upper reaches, has to slog its way through a weed-strangled gully.

Both the creek and the Fernleigh Track are about to enter another gem of the Hunter: Glenrock State Conservation Area.

Tomorrow: The journey towards the tunnel, as we near the end of the track.

Read more:

"On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 1

"On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 2

"On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 3

"On The Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 4