As reported antisemitic incidents in the U.S. in 2022 soared to an all-time high, the White House began developing plans to combat this hate, proclaiming in an official statement, “antisemitism has no place in America.”

The White House’s recommendations, expected soon, are based on conversations with a thousand stakeholders, including me, a scholar of American Jewish history. Based on a preview of the plan made public on May 17, 2023, it includes more than “100 calls to action” to Congress, state and local governments and the private sector, emphasizing the need for deepening awareness of antisemitism and of Jewish heritage in the U.S.

That heritage has two sides. Its bright side honors the achievements of America’s Jews and their many contributions to this nation. Its darker side contains a long history of antisemitism from Colonial days to today.

Governors, generals and members of Congress

During the recent celebration marking Jewish American Heritage Month at the White House, Jewish accomplishments were spotlighted. Michaela Diamond and Ben Platt, stars of the Broadway revival of the musical “Parade,” performed. That these actors, the show’s book writer, Alfred Uhry, and its composer, Jason Robert Brown, are all Jewish attests to Jews’ presence and contributions to American theater, the arts and beyond.

Yet “Parade” tells the story of one terrible episode in the history of American antisemitism.

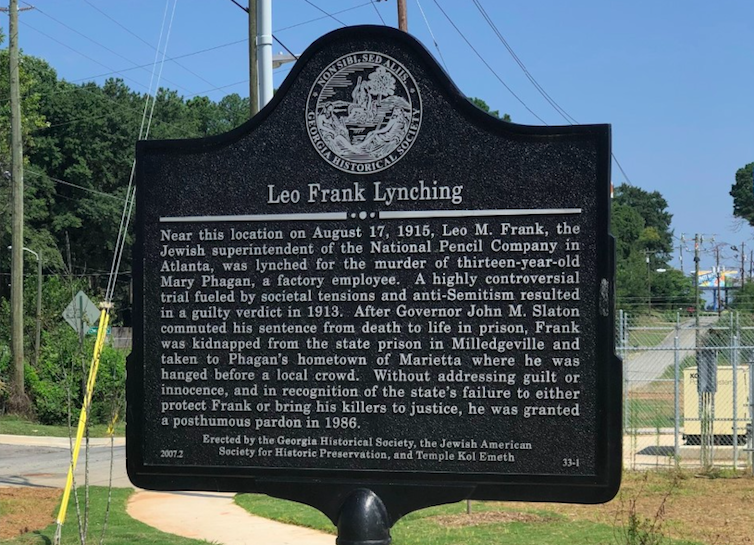

In 1913, Leo Frank, the manager of an Atlanta pencil factory and a Jew, was accused of having murdered one of his teenage workers. Frank maintained his innocence, and the trial became a national media circus.

Mobs gathered outside the courtroom. Frank’s attorney told the court, had Frank not been a Jew, he never would have been prosecuted.

Even as the trial judge questioned Frank’s guilt, the jury convicted him, and Frank was sentenced to hang. Two years later, after Georgia’s governor commuted that sentence to life imprisonment, a gang of vigilantes, without firing a shot, kidnapped Frank from jail and lynched him.

Antisemitism had arrived in America 250 years before Leo Frank’s murder. In September 1654, after 23 Jewish refugees fleeing the persecution in colonial Brazil landed in Manhattan, the colony’s governor, Peter Stuyvesant, tried to eject this “deceitful race” of “blasphemers” and “enemies.”

He failed.

Yet during the Civil War, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant did expel Jews from his military district, the District of the Tennessee, which spanned from the southern tip of Illinois to the Gulf of Mexico, an order President Abraham Lincoln countermanded.

In the 1940s, Rep. John Rankin, a Democrat from Mississippi, railed against the Jews from the House floor, claiming that Jews “have been for 1,900 years trying to destroy Christianity, and everything that is based on Christian principles.” They had already “virtually destroyed Europe,” ranted Rankin, and were now doing the same to America.

‘Misfortune’ to be a Jew

Powerful voices from the private sector joined governors, generals and members of Congress in spouting antisemitism.

In May 1920, the newspaper The Dearborn Independent, owned by the automobile tycoon Henry Ford, ran the headline “The International Jew: The World’s Problem.” For the next 91 weeks, the weekly ran a series of articles decrying Jewish power and Jews’ dangerous influence on American life.

The paper’s circulation soared as copies were distributed in every Ford dealership and sent to every member of Congress.

News of Ford’s antisemitism even reached Adolf Hitler, who, in March 1923, in the early days of the Nazi Party, told a Chicago reporter how much he admired Ford’s anti-Jewish policies. If he could, Hitler said, he would send some of his so-called “shock troops” to America to support Ford.

Encounters with antisemitism, and not only those from public figures, linger in the memories of American Jews. My book “America’s Jewish Women: A History from Colonial Times to Today” highlighted some of them. In the 1880s, a Philadelphia writer ruefully recalled a teacher saying: “It is your misfortune, not your fault, that you are a Jew.”

In 1945, just days after World War II ended, Bess Myerson, a Jewish woman from the Bronx, was crowned Miss America. Heading out on tour after the pageant, this Miss America was turned away from what were called “restricted” hotels, which did not admit Jews. Three of the pageant’s sponsors refused to feature a Jewish Miss America in their ads. Myerson spent part of her year wearing her crown speaking out against antisemitism. Meanwhile, returning American GIs who had liberated the concentration camps had seen with their own eyes just where antisemitism could lead.

The antisemitism the White House hopes to combat today rests on this history and much more.

The White House plan comes just as the trial of the man accused of the deadliest hate crime against American Jews, the murder of 11 worshippers in a Pittsburgh synagogue in October 2018, gets underway.

Pamela S. Nadell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.