Scientists estimate that the earliest biological entities began to appear on Earth more than 4 billion years ago.

"There was a sort of primordial soup from which certain organic molecules were formed. These were precursors to RNA and DNA," carbon-containing molecules which combined and organized themselves into a sequence of biological reactions, said computational biologist Karthik Anantharaman from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. These first microbes would have been extremely simple.

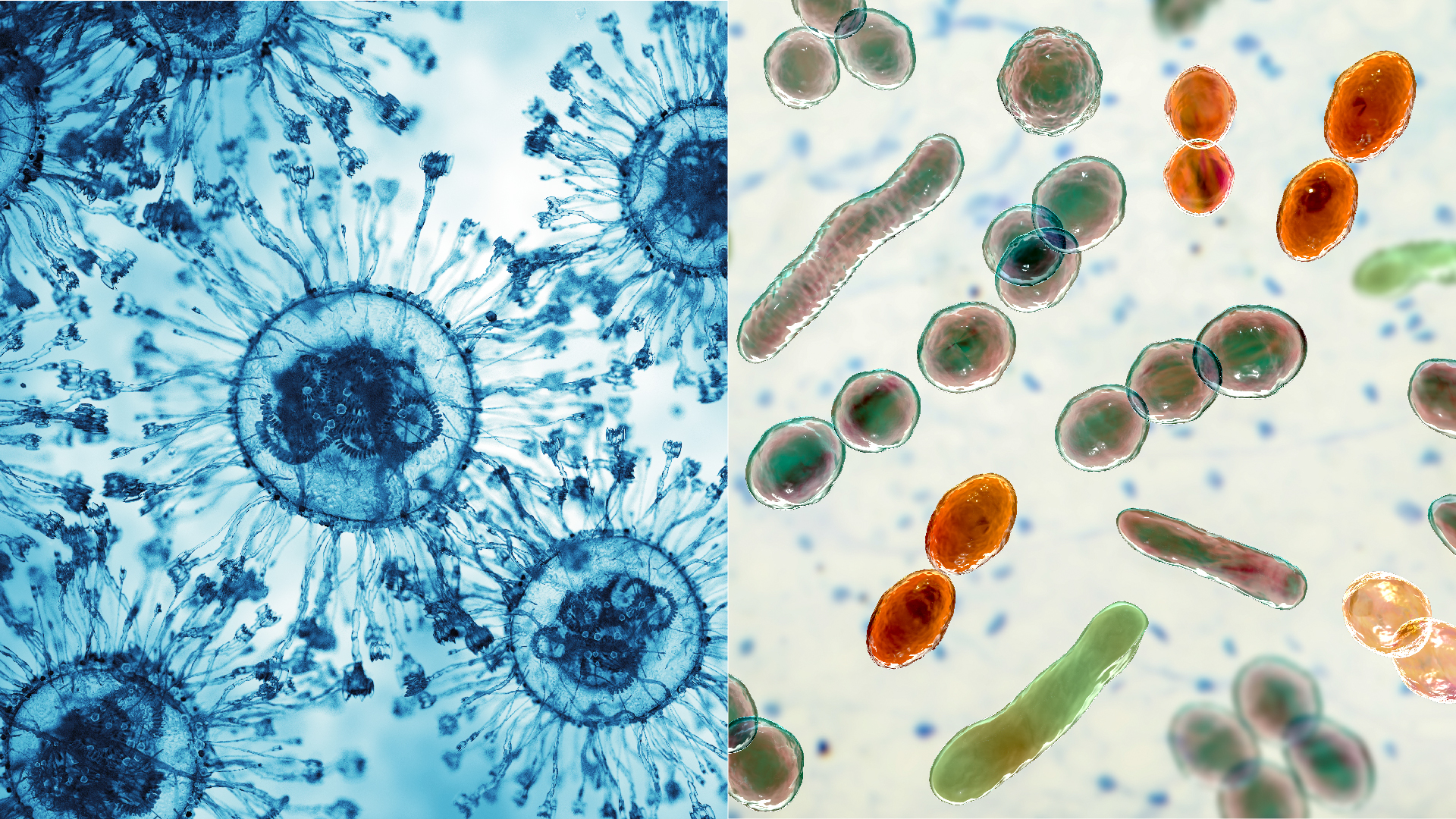

But were they viruses or bacteria?

Scientists don't have a conclusive answer, partly because it's difficult to recreate more than 4 billion years of evolution. Bacteria are single-celled organisms that can reproduce and exist independently. The oldest fossils of bacteria date back around 3.5 billion years. Genetic data suggests the first cells are even older, dating back at least 4.2 billion years. This doesn't help settle the matter of whether viruses or bacteria emerged first, however, because that same data suggests the first cells were already living in an ecosystem teeming with viruses.

Meanwhile, viruses degrade more easily than bacteria, so there are no physical fossils of viruses.

Related: What was the first animal on Earth?

And dating viruses through changes in their genetic sequence isn't helpful, either, because viruses can mutate significantly faster than bacteria can.

"The sequence changes quickly from an evolutionary point of view," said Gustavo Caetano-Anolles, a bioinformatician at Carle Illinois College of Medicine. "Over 4 billion years of evolution, the sequence has changed over and over again until it becomes unrecognizable, and that's called saturation."

But viruses are not alive. They do not have a metabolism or replicate unless they infect a cell and use the host's resources to replicate. Because viruses need a host, that would suggest bacteria evolved first, right? Not so fast.

In fact, until very recently, most scientists thought viruses emerged from the primordial soup before bacteria.

One hypothesis for life's emergence, called the "RNA World," was first proposed by Alexander Rich in 1962: In the beginning, before the first biological entities formed, individual RNA molecules catalyzed simple chemical reactions and stored basic genetic information within their sequences, he posited. At some point, these molecules became encapsulated, creating early life, and it was only later that the more complex molecule DNA began to emerge.

"All bacteria have double-stranded DNA, but viruses have different kinds of structure — there are DNA genomes, RNA genomes, double-stranded, single-stranded …" Anantharaman told Live Science. That some virus types contain just RNA strongly suggests that viruses predate cells, Anantharaman said.

The virus-first hypothesis is still the most widely accepted among evolutionary biologists. However, more recent discoveries have challenged it.

The bacteria-first theory, also known as the reductive hypothesis, picked up support in 2003 when French researchers discovered a giant virus in the sludge of a water tower in Bradford, England. Previously misidentified as a bacterium, the discovery of the Mimivirus challenged microbiologists' longstanding theories on viral evolution. "These viruses were almost as big as bacteria and had pieces of machinery needed to make proteins," Caetano-Anolles said. "They were like an intermediate form between cells and viruses."

The researchers proposed that perhaps these viruses evolved from ancient cells — but rather than increasing in complexity as they evolved, the cells "went reductive," gradually stripping away their different biological functions to become specialized and completely dependent on host cells.

However, Anantharaman and Caetano-Anolles have doubts about this theory. "It's a very general hypothesis, and the people who support it often focus on very specific examples," Anantharaman said.

Related: Do other viruses have as many variants as SARS-CoV-2?

For Caetano-Anolles, co-evolution from a single common ancestor seems to be the most likely origin of viruses and bacteria. "We have been incorporating viral material into our makeup from the beginning," he said. "Perhaps the virus is really part of the entire process of the cell and should be thought of as an integrated element."

Caetano-Anolles' own research looks at other structural features that may hold "memory" of ancient viruses and bacteria. He believes commonalities in the shapes of protein folds in viruses and bacteria, coded for within the genetic sequence, suggest a possible joint origin. "We've generated a clock of folds, so we have the timeline — and it's the universal folds, the ones that are common to everything including viruses, which come first," he said.

Researchers across the field continue to discover evidence in support of each origin theory. However, we're unlikely to reach a conclusive answer, Anantharaman said.

"We're trying to infer an event that happened 4 billion years ago," Anantharaman said. "We can do experiments to support one hypothesis or another, but in reality, it's a chicken-and-egg situation."