A year marked by escalating US-China tensions ended with tentative signs that the relationship might yet improve. Sam Sachdeva looks at what 2023 could bring for the Great Power rivalry, and the main issues likely to set the agenda.

For most of 2022, there was little reason to take a glass-half-full approach to the relationship between the United States and China.

Competition in the trade and technology spaces continued, while Nancy Pelosi’s controversial visit to Taiwan in August threatened to put bilateral ties into a downward spiral as Beijing retaliated by cutting cooperation in a wide range of areas.

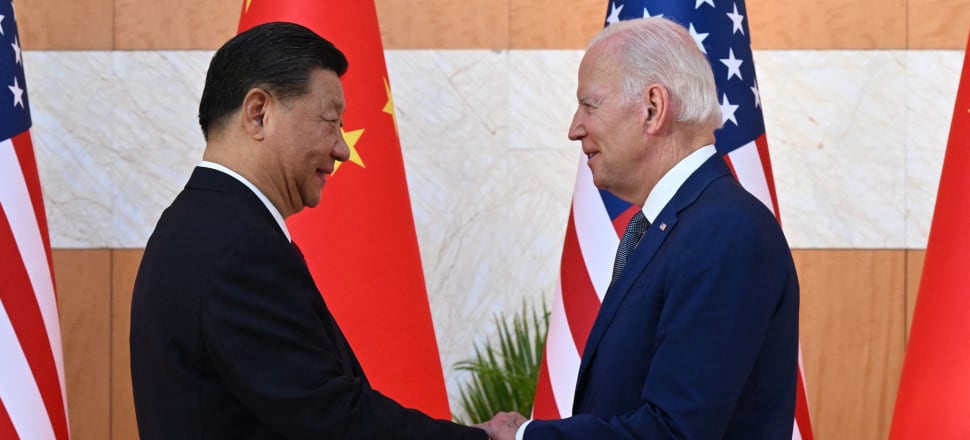

But just before the year drew to a close, there was a glimmer of hope, as US President Joe Biden and China’s leader Xi Jinping met on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Bali and spoke about managing their differences in a more constructive manner.

READ MORE: * What Japan’s hawkish move means for NZ * The truth about China

It’s hard to take too much from one face-to-face meeting, but as NZ Contemporary China Research Centre director Jason Young says, there are at least some grounds for optimism.

“It's not an improvement of relations, so to speak, but a stabilisation…which I think is positive, because then one would hope that the US and China would have mechanisms and understandings in place to manage any type of tensions that emerge.”

Tensions at home, rather than with each other, may be consuming much of Biden and Xi’s time at present, however.

In the US, a new Republican-controlled House has already started its mission to make Biden’s life hell.

The domestic challenge is even more profound in China, which is in the midst of its most serious Covid-19 outbreak since the pandemic began, having abandoned its zero-Covid approach late last year.

“China's not different to any country around the world: when Covid begins spreading in the community, then there's all sorts of challenges,” Young says, from public health to the economy and beyond.

Xi’s decision to drop quarantine measures and other Covid controls was a striking concession in the face of highly unusual public dissent. The question now is how the population responds to a wave of illness and death, and what that means for the government’s ability to focus on issues beyond its borders.

“It wouldn't be totally surprising to me if we just see a kind of a hunkering down and maybe a bit less of some of the assertive international actions that we've seen from China over the last few years,” Centre for Strategic Studies director David Capie says.

Talking tough

While problems closer to home could act as a distraction for both countries, domestic politics may actually play a role in aggravating tensions.

Ahead of the US midterms, McCarthy had pledged to create a new select committee to investigate the threat posed by China; the proposal passed the House of Representatives by 365 votes to 65, a further sign that for all the rancour between Democrats and Republicans, Beijing remains a bipartisan concern.

As Capie notes, with the countdown to the 2024 presidential election already underway, the China debate “might turn into a competition of who can take the tougher line”.

“There doesn't seem to be an electoral downside to taking a muscular posture on China, whereas the factions that are emerging a little bit around Russia and Ukraine are quite intriguing, especially on the Republican side,” Capie says.

Whether campaign trail rhetoric evolves into tangible action from whoever is occupying the White House come 2025 is another matter, but tough talk alone could act as a barrier to improving bilateral ties this year.

China has its own presidential election to deal with this year too, albeit one where the outcome is essentially predetermined.

In March, the National People’s Congress will meet to decide its next president. With the leader having already won a third term as the CCP’s general secretary, and the abolition of presidential term limits in 2018, the stage is set for him to break precedent and enter a second decade in power.

Exactly what Xi does with that new mandate is one of the crucial issues under the microscope in 2023. Some have speculated the newly emboldened leader could take an even more hardline approach, but Young believes one of his top priorities - at least in the immediate future - will be on bedding in what is “quite a significant shift” from the two-term presidencies of recent decades.

“I'm not sure if it would change things significantly,” Young says of any foreign policy shifts in a third Xi term, instead predicting a continuation of the more proactive approach seen over the past decade.

The Global Development Initiative and the Global Security Initiative, two multilateral frameworks launched by China in recent years, have to date received little attention outside of the country. But Young believes that could change in 2023, as Xi and the CCP put more emphasis on efforts to shape the world order to their own design.

The Global Development Initiative has already received support from a wide range of countries as well as the United Nations, given its stated connection to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 and the economic benefits on offer for participants.

Work in the security space may be a tougher sell, Young says, noting Beijing’s failed attempt at a Pacific-wide security pact last year.

“It's basically a criticism of the current international security environment, and saying that security should be focused within the United Nations system and we should move away from or criticise the current sort of alliance, ‘hub and spoke’ system that's led by the United States … it's very, very abstract, ad I think that they'll really struggle to have that policy play well.”

'The year of co-opetition'

Then there is the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, an American attempt to counter China’s financial might with its own set of agreements related to infrastructure development and trade.

Details are still thin on the ground, with another round of negotiations taking part in India next month, but Young believes an American emphasis on the importance of trusted supply chains and following economic norms could damage China in the long run.

Indeed, ‘decoupling’ from Beijing ramped up even further last year, with the US passing legislation to encourage domestic manufacturing of semiconductors while also placing export controls to cut off Chinese access to American technologies.

Scott Kennedy, a senior adviser at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, described 2023 as “the year of ‘co-opetition’ with China” in an interview with the South China Morning Post last week, suggesting the US would continue to clamp down on sensitive technology while accepting a broader breaking apart of the two economies was unlikely to be feasible.

Taiwan is also certain to remain a big issue in 2023, with the fallout from Pelosi’s trip still simmering down.

While there has been speculation about a Chinese invasion within as little as two years, Young believes the status quo to continue with red lines firmly in place on each side.

“The basic problem there is that there is a dispute and it hasn't been resolved ... obviously they [China] want it, they will claim it, they will put pressure on other countries around the world to adhere to the interpretation of Taiwan in the world - but it just makes no sense to me to think that they would do something rash in the short term.”

Then there are the unknown unknowns. With China’s territorial disputes stretching ever wider, a number of potential flashpoints could yet set the agenda out of nowhere.

“What might be the issue that really sparks the sharpening or further deterioration of relations? It's easy to imagine plenty of contenders, but it's hard to see which one might be the one that comes to the surface,” Capie says.

With structural incentives for increased competition on both sides, the risks of miscalculation remain high - making further conversations between Biden and Xi, and across the board, critical in the year ahead.