The mystery of the weird, bright patterns on the moon called lunar swirls has moved a step closer to being solved. It's thanks to the discovery that the composition of lunar dirt, or regolith, plays a major role in creating the swirls' alternating light and dark patterns.

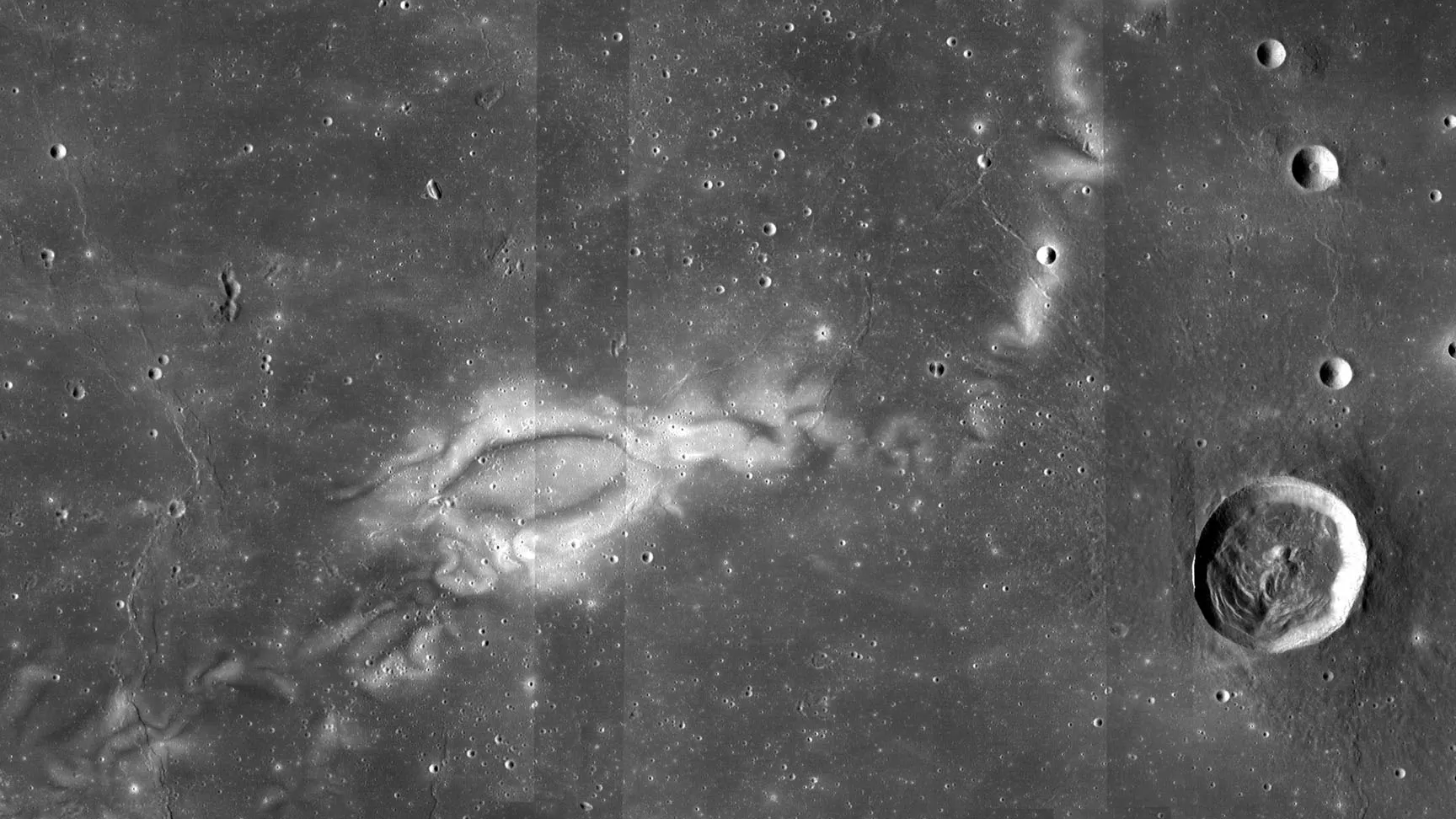

The most famous of the lunar swirls is Reiner Gamma, which is visible in Oceanus Procellarum even to amateur astronomers through a backyard telescope. These features are linked to magnetic anomalies under the surface of the moon, but exactly what process is creating them has been a mystery for decades.

"The scientific community has long been examining the differences between the bright and dark regions in these distinctive albedo markings," Debrah Domingue, a scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona and author of a study about the new findings, said in a statement.

A breakthrough came in 2023 when researchers at the Planetary Science Institute (PSI) used observations from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to determine that the bright parts of the swirls are, on average, a few meters lower than dark, or "off-swirl," areas. Now, new research from PSI scientists led by Domingue suggests that the composition of the lunar regolith also plays a large role in the creation of the swirls.

Related: India's Chandrayaan-3 lunar lander barely kicked up any moon dust. Here's why that matters

Domingue's team looked at three possible causes for the light markings: differences in what the regolith is made from, the size of the grains in the regolith, and how compact the regolith is. The researchers concluded that composition, particularly the presence of plagioclase (an aluminum-bearing mineral) and ferrous oxide (an iron compound), was the key factor — but not necessarily the only factor.

"Grain size differences might also contribute to the brightness variations, but we do not see differences in compaction within our study area," said Domingue. "We also note differences in grain types and structures between bright and dark area soils. This indicates that there is more than one process at work to form these features."

Currently, there are three leading explanations for the swirls that might also explain their links to surface elevation and composition. One is that a magnetic field, perhaps the result of a dense iron asteroid impacting a particular region on the moon long ago, is shielding the surface from space weathering imparted via cosmic rays and the solar wind. The pattern of the swirls may reflect the lines of that magnetic field.

Another related explanation is that the magnetic field is levitating electrically charged dust and sorting it by composition and grain size. The third option, however, is a little different. It suggests the swirls are the result of an ancient comet impact. In this case, turbulence in the comet's coma (the cloud of ice and dust that surrounds the head of the comet) would scour the lunar surface just before the impact and expose fresh lunar material while magnetizing the surface due to the violence of the impact itself.

A fourth possibility was also put forward earlier in July; researchers suggested the swirls are produced by magnetized lava beneath the surface of the moon.

But rather than ruling any of these explanations out, the new results actually seem to support multiple models.

"There are a couple of processes that have been put forth for explaining the presence of these features on the moon, yet the evidence is contradictory,” said Domingue. "Interpretation of this new evidence, in the context of past work, all indicates that these features are the result of a complex interaction of multiple processes and that laboratory studies will be needed to deconvolve the relative roles of these processes in the formation of lunar swirls."

The findings of Domingue's team were published on July 18 in The Planetary Science Journal.