Rain was pouring outside of Trish Green’s home in Austin as she was getting ready to do laundry the morning of Sunday, July 2.

When she walked down to her basement where the washer was, the 59-year-old could not believe her eyes. The space was flooded with three feet of dark and murky water with dirt and debris floating around. The smell was unbearable.

“There was immediately no hot water, the furnace was not working, it was destroyed. So was the refrigerator, and then a deep freezer and a washer and dryer,” Green said, recalling the initial damage done.

Within 24 hours, most of the water had receded down a floor drain, but Green still couldn’t fully process what had happened.

“It’s almost like a mental paralysis, ‘cause you’re like, well, where do I go from here?” she said.

On July 2, a record-setting rainstorm dumped 9 inches of rain on some parts of the Chicago area. Green was among more than 1,400 Chicagoans who filed reports of flooded basements to 311, the city’s non-emergency helpline.

Thousands of additional reports poured into the hotline throughout July, as more Chicagoans grappled with flooded basements, standing water, waterlogged appliances and growing mold and mildew.

From July 2 to July 18, more than 12,000 basement flooding reports were filed with 311, more than the number of basement flooding reports filed in all of 2021 and 2022 combined, according to a WBEZ analysis.

No other month since 2019, the earliest year 311 flooding data is available online, comes close to July’s current volume of reports.

A system overwhelmed

Both city and regional officials say record rainfall caused the unprecedented number of flooded basements.

To prevent flooding, the region relies on its multiple sewer systems and the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District’s (MWRD) Deep Tunnel system — a massive 110-mile underground tunnel designed to hold 2.4 billion gallons of stormwater.

But when rain falls as hard and as fast as it did on July 2, those systems can be overwhelmed, said Catherine O’Connor, director of engineering at MWRD.

“There is no system in the world that would be able to convey that much water, and when the system becomes overwhelmed, the combined stormwater and sanitary waste does back up into basements,” O’Connor said.

Experts say a warming climate is changing weather patterns in the Chicago area and will increase the frequency of storms like the one on July 2.

“We can expect to see more of this where you’re gonna see large precipitation events leading to floods,” said Donald Wuebbles, professor emeritus of atmospheric sciences at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “It’s going to continue to get worse, and we need to plan for that.”

O’Connor said the MRWD is doing as much as it can to alleviate flooding, but that “in older parts of the system, we still have more work to do.” She said the agency currently has more than 85 active projects to manage local stormwater. Since 2008, the agency has spent $506 million on stormwater and green infrastructure projects, according to Allison Fore, an MWRD spokesperson.

“A complex set of sewer infrastructure, stormwater infrastructure and increasingly severe and intense rainfall patterns [is] creating a perfect storm, forgive the pun, that is damaging our neighborhoods and people’s homes,” said Ryan Wilson, manager of water resources at the Metropolitan Planning Council, a planning and policy nonprofit that focuses on the Chicago region.

“The infrastructure we have, it’s not the infrastructure we need,” Wilson said.

“Every time it rains, I fear that water is going to come back in here”

The impact of basement flooding would be less severe if basements were just empty storage spaces, but that isn’t the case for many homes in the Chicago area.

In Cook County, there are more than 24,000 basement apartments, and nearly half a million basements that are finished into living spaces like recreational rooms, according to data from the Cook County Assessor’s office.

Thelma F. McGregory-Bowns, 68, lives in a two-flat along a tree-lined street in Austin. Her 49-year-old daughter lives in her basement unit.

On July 2, McGregory-Bowns stood in shock as she saw six feet of brown, murky water rushing into her daughter’s basement apartment “like a river” through a back door.

The hot water tank, furnace, washer, dryer and all of her daughter’s clothing and personal belongings were damaged or had to be thrown out. McGregory-Bowns estimates it will cost at least $10,000 to clean and replace everything. She said it’s an amount neither she nor her daughter can afford.

“It’s devastating to her because that was all her belongings and the majority of that stuff was brand new,” McGregory-Bowns said.

For Trish Green, getting help right away was a challenge. For three weeks, stormwater and debris sat in her basement. That’s how long it took before she could get a professional to help clean out her basement because they were backlogged with calls from others who were impacted.

Green said she worried about the health risks of being exposed to mold and mildew and was initially quoted $5,500 to have her basement professionally cleaned.

Of the residents WBEZ interviewed, many did not know their basements could flood and none have flood insurance.

“I’ve been on this earth for 68 years. I’ve never seen water come in anybody’s house like that,” McGregory-Bowns said. “Every time it rains, I fear that water is going to come back in here.”

Who’s calling 311 about flooding?

Even with a record number of calls this month, 311 totals are likely an undercount of the actual number of basements that flooded.

“People will only use 311, one, if they [know about] it, and two, if they trust that the government will actually do something about it,” said Cyatharine Alias, manager of community infrastructure and resilience at Center for Neighborhood Technology, a Chicago-based urban sustainability nonprofit.

Shame around flooding and fears that reporting it may diminish property values can also prevent people from reporting it to 311, said Alias.

Despite these drawbacks, advocates say 311 reports are one of the only sources of data on where urban flooding occurs.

Since 2019, the communities with the most flooded basement reports were Austin, Portage Park, Roseland and West Garfield Park. Each has had more than 1,000 reports filed.

Since 2019, roughly 52% of all 311 basement flooding reports came from majority-Black community areas. Another 18% came from majority-white communities, 16% from majority-Latino communities and 12% from communities with no racial majority, according to a WBEZ analysis.

Andrea Cheng, commissioner with the Department of Water Management, said basement flooding calls tend to come from parts of the city experiencing the heaviest levels of rainfall.

About four in every 10 reports of flooded basements to 311 in July came from the Austin neighborhood, according to WBEZ’s analysis. Cheng said the West Side was one of the areas hardest hit by the storm on July 2.

Getting assistance

In Austin, groups are taking flood relief matters into their own hands.

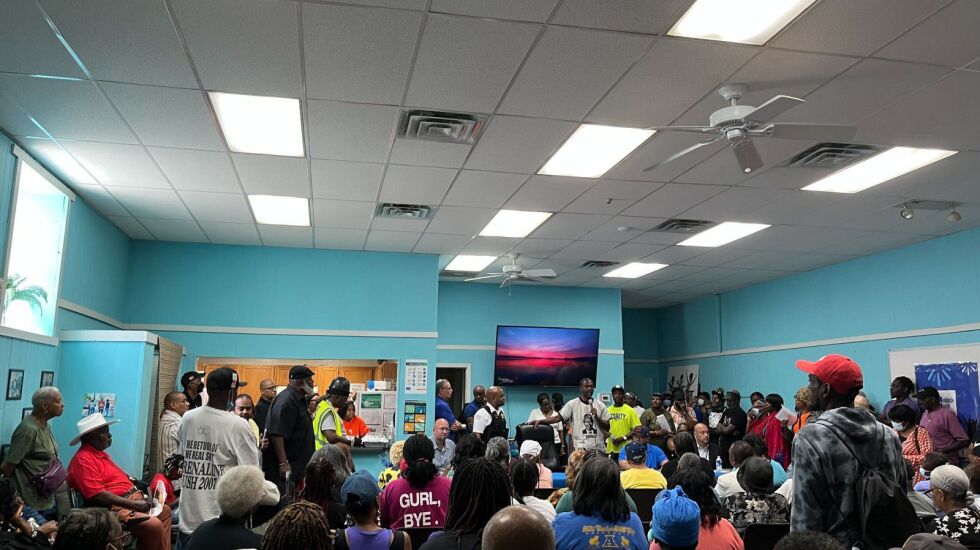

On July 18, more than two weeks after basement flooding in the area began, the Westside Health Authority in Austin hosted a community meeting where elected officials gathered to hear the concerns of residents still dealing with the aftermath of flooding.

State Rep. La Shawn K. Ford, D-Chicago, strongly urged Austin residents to file 311 complaints, in order to draw state and federal attention to the sheer scale of flooding in their neighborhood and to receive disaster relief money from the federal government.

“If you’re not documenting that you have an issue, then it’s as if there’s no issue,” Ford told the overflow crowd of more than 200 residents who had experienced flooding.

Ford explained that between $1 million to $5 million could be allocated to a local nonprofit through the competitive HAF Home Repair Program grant offered by the Illinois Housing Development Authority to provide up to $60,000 per house for long-term recovery and floodproofing. Ford said documenting the basement flooding in Austin through the 311 service can improve the community’s chances to win the grant.

Ford said the grant money is typically available only in January, but he hopes to expedite the funding given the urgency of repairs needed in Austin and nearby neighborhoods.

Call 311 or visit 311.chicago.gov to report flooding in your home or on the street. Always include your phone number in the request so 311 can contact you. Here is what you need to know if your basement floods.

Click here for more information on how to file a flood claim with your insurance company or with FEMA. Make sure to take photos of the damage and any items destroyed.

For information about flood prevention measures, visit the city’s Department of Water Management website here or the MWRD’s flood prevention 101 webpage.