The map below shows the 2019 federal election results adjusted for redistributions in Victoria and Western Australia. Victoria gained a seat (Hawke), while WA lost one (Stirling). Hawke is a notional Labor seat, while Stirling was a Liberal seat, so Labor gained one notional seat by redistribution.

ABC election analyst Antony Green published the 2022 election pendulum last August. The Coalition notionally holds 76 of the 151 House of Representatives seats, Labor 69 and there are six crossbenchers. Labor needs to gain four net seats from the Coalition to be the largest party, and seven for a Labor majority.

Of the 151 seats, 142 use the Labor vs Coalition margin in 2019, with the six seats won by crossbenchers using that crossbencher’s margin. The three remaining seats (Grayndler (NSW), Cowper (Vic) and Wills (Vic)) use Labor’s margin against the Greens. The pendulum does not account for Craig Kelly’s defection from the Liberals to the United Australia Party in Hughes, as he was elected as a Liberal.

Electorate colours are blue for Coalition, red for Labor and black for crossbenchers. Distinctions between Liberals, Nationals and Queensland’s LNP have been ignored. Darker colours indicate safer seats. Margins in the maps reflect margins on the pendulum, but crossbench-held seats are always black.

The initial map of Australia appears very Coalition-dominated as the Coalition easily wins most large regional seats. You need to zoom in on big cities such as Sydney and Melbourne to see where Labor dominates.

Where the biggest swings are likely to occur, and where the Coalition could resist

Last May, I wrote about how whites without a university education had moved to the right in the United States, United Kingdom and Australia. However, better-educated people have shifted to the left relative to the national vote.

Read more: Non-university educated white people are deserting left-leaning parties. How can they get them back?

If this pattern continues at this election, the biggest swings to Labor are likely to occur in seats that have long been seen as wealthy urban Liberal heartland. Such areas include Sydney’s north shore and Melbourne’s inner east.

However, the Coalition is likely to do better in swing terms in regional seats with high levels of whites without a university education. Labor could have difficulty regaining the marginal Tasmanian seats of Bass and Braddon that were lost in 2019, and could be threatened in the coal-mining seat of Hunter (NSW).

I don’t expect Labor to rebound in regional Queensland after it was utterly shellacked there in 2019. Fortunately for Labor, Australia’s population is far more urbanised than in either the UK or the US. I have researched this for a future article.

As price rises on essential items such as food affect low-income people more, inflation may damage the Coalition with these voters, who are also likely to be non-university-educated. So Labor could do better with non-university-educated whites than the above discussion expects.

Polls in WA have had large swings to Labor, but will those swings hold up until election day?

At the March 2021 WA state election, the Coalition was virtually obliterated, but federal elections are different from state elections, and WA has historically been a conservative state at federal elections.

Read more: As the election campaign begins, what do the polls say, and can we trust them this time?

Don’t trust the Queensland state breakdowns

Australian polls usually release their state breakdowns with every poll, but Newspoll typically does its breakdown once a quarter for all polls conducted in that quarter. The smaller state samples mean that estimates of state votes and swings are far more volatile than the national figures.

The best way to analyse state level data is to aggregate it, which The Poll Bludger does with BludgerTrack.

Labor currently has 53.9% two party in NSW, a 5.7% swing since the 2019 election, 56.5% in Victoria, a 3.4% swing, 50.4% in Queensland, an 8.8% swing, 55.1% in WA, a 10.6% swing and 58.4% in SA, a 7.7% swing. Sub-samples from Tasmania and the territories are not large enough for meaningful analysis.

You can use these state-level swings on the map above, which show the seats most likely to fall to Labor on current polling. You could also plug them into Antony Green’s ABC calculator. But don’t trust the Queensland swing of almost 9% to Labor.

Federal Labor has a long history of underperforming its polls in Queensland, and this was particularly the case in 2019. Polls in Queensland in 2019 suggested a 50-50 tie or 51-49 to the Coalition, but the actual result was a crushing 58.4-41.6 to the Coalition.

The last Newspoll breakdowns for the March quarter gave the Coalition a 54-46 lead in Queensland, and this is likely closer to Queensland’s voting intentions than current breakdowns, as Newspoll now weights by education.

Coalition marginals

These maps show the four most marginal Coalition seats, followed by maps of the four most marginal Labor seats. I will briefly comment on each seat.

As I said above, Bass could resist the Labor swing as it’s a regional seat which was gained in 2019. The new Liberal MP can expect a “sophomore” surge. A Telereach poll had the Liberals well ahead in Bass, but seat polls are unreliable.

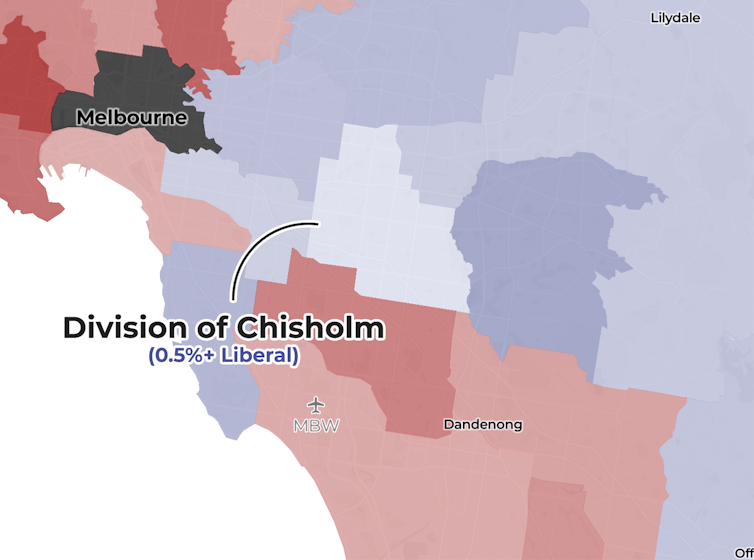

Chisholm is an inner city seat that should be easily gained by Labor, although Telereach had the Liberals well ahead here.

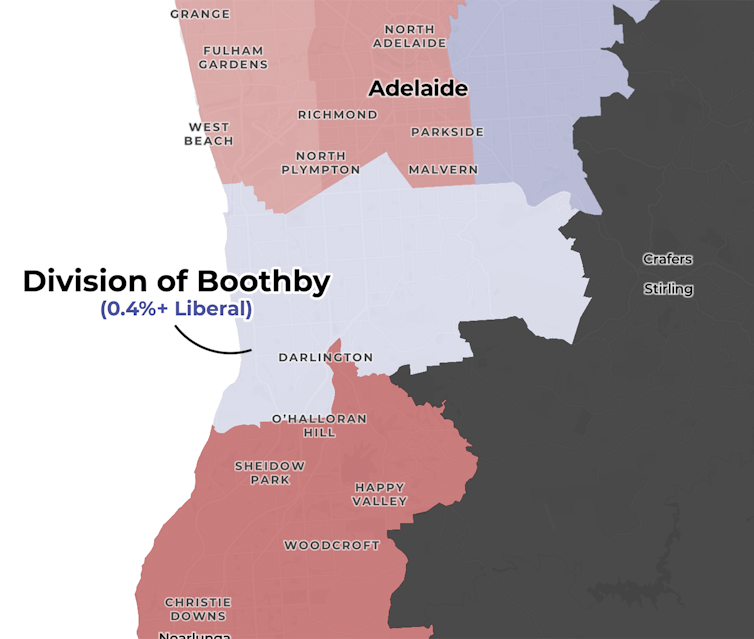

Boothby is another inner city seat, and both Telereach and uComms seat polls have Labor way ahead.

Braddon has a bigger Liberal margin than Bass, and was also gained from Labor in 2019. If the Liberals are holding Bass, they should also be holding Braddon. But a uComms seat poll gave Labor a 53-47 lead, although analyst Kevin Bonham estimated 50-50 from the primary votes.

Labor marginals

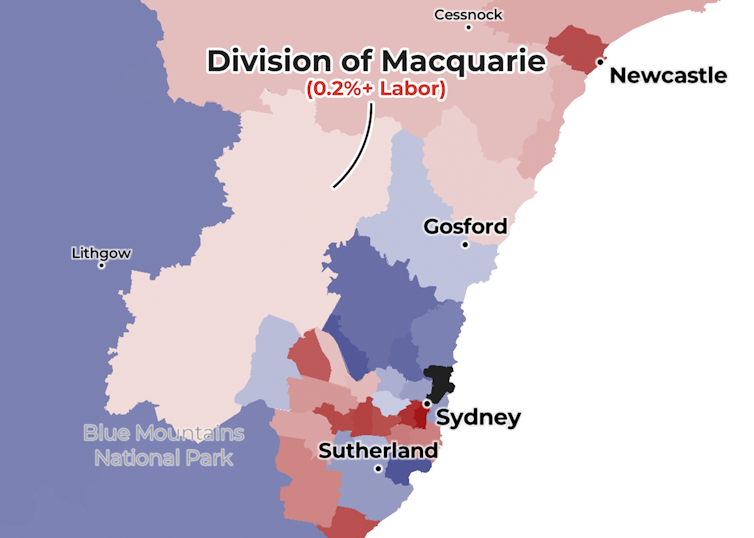

With a strong NSW swing, Labor should have no trouble in Macquarie.

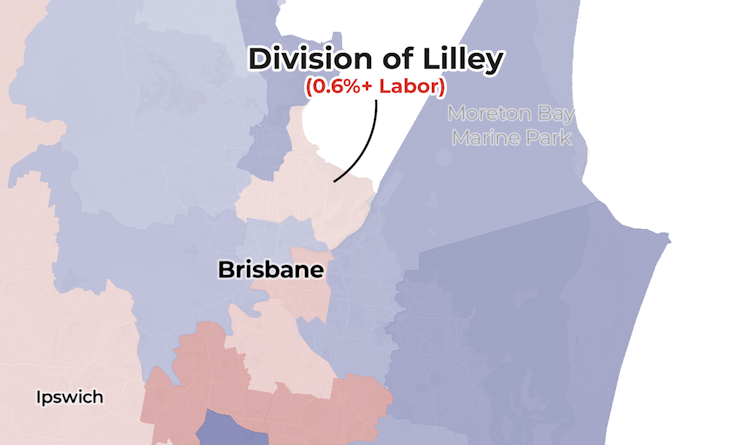

Lilley is an urban Queensland seat, and Labor should retain easily.

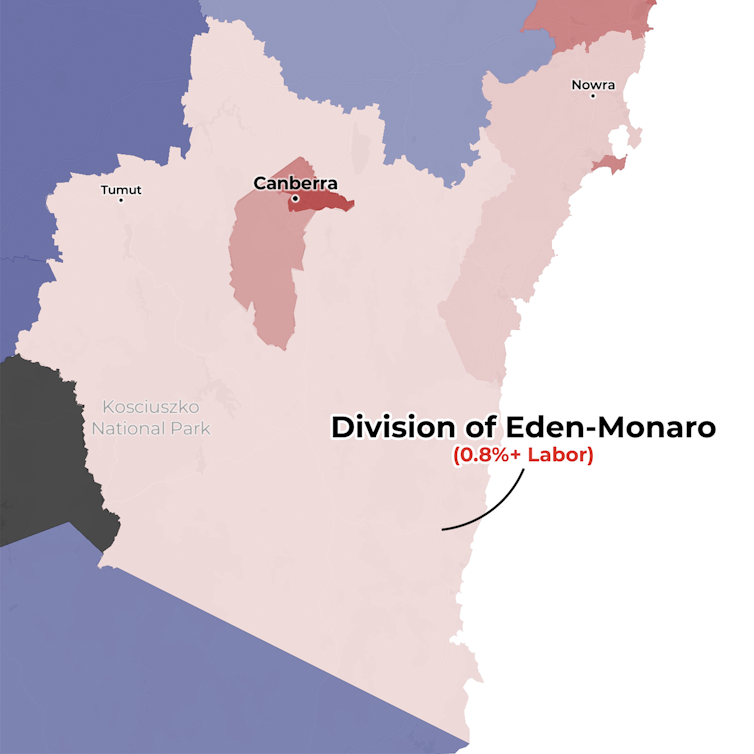

Eden-Monaro is a regional NSW seat, but Labor should hold given the Queanbeyan regional city is located in this electorate.

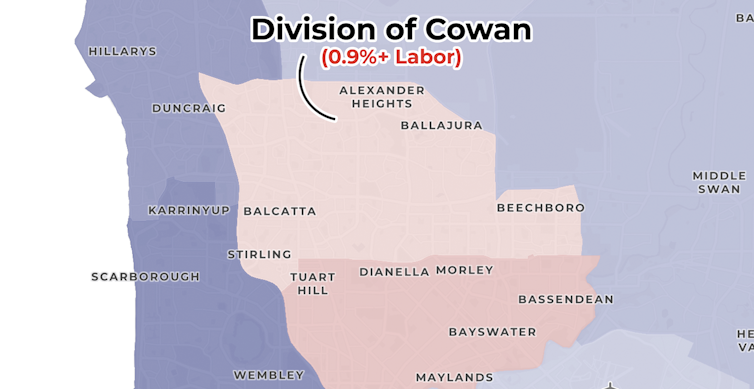

With a 10%+ swing to Labor in WA, Labor will easily hold Cowan.

Adrian Beaumont does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.