Victor Billot reviews a biography of a great New Zealand Communist

I arrived in Auckland in 1996. It was not a particularly welcoming place. I’m not sure what I was expecting, turning up from Dunedin, my hometown which had started by then to seem small and restrictive. New in the big smoke, I bumped around and felt on the outside of things, even if I didn’t know what exactly those things were. Steady work was hard to find. I lived off Great North Road in a damp flat. Funds were low and the grimy urban vibe wasn’t proving to be the adventure I had imagined.

I eventually got taken on by Dymocks bookstore out the back of Queen Street. I still remember catching the bus home the day I got the job. A vast sense of relief flooded through me – I had an income. After getting used to my new routine folding up cardboard boxes and stuffing them in recycling skips, I decided to join the union. As far as I knew, the National Distribution Union (NDU) represented retail workers. There were no other members at my workplace – if there were, they were keeping quiet. There was no pressing need for me to join, but unlike 95 percent of the rest of my age group, I was intent on signing up. It was what a good socialist would do.

I left a phone message a couple of times but no one got back to me. Dymocks was probably not a high-priority site for the class struggle. I was leafing through the jobs pages in the Herald wondering if anything better might be out there, when I came across an advertisement for publicity officer for the same union I was trying to join as a member. This coincidence was too good to be true. I put in an application and soon found myself called to a meeting in a dim room in a Kingsland office building. The interview panel comprised of one middle-aged Cockney geezer (I’m pretty sure he had a gold neck chain) and a quiet old guy.

The geezer did most of the talking. I did okay and said the right things. At least I knew what a union was. The old guy didn’t say much but just as the interview ended he said to me, in a not unfriendly way, “You’re not going to bugger off overseas after a few months are you?”

No, I assured him; even though that was exactly was what was on my mind.

The geezer was Secretary of the National Distribution Union, Mike Jackson. The perceptive old guy was the President of the National Distribution Union, Bill Andersen. I got the job. I did bugger off overseas, but it was after a year, so I told myself I had technically kept my word. And in that year, I got to know Bill Andersen a little.

The first thing to say about Bill Andersen’s biography Comrade is it is a very good book. In fact I would say it is one of the best recent New Zealand social and political biographies. Thorough, insightful, readable: author Cybèle Locke has done her subject proud. It deals with Andersen the public man – after covering his childhood and youth, there is not a lot about his personal or family life. There is not much of a sense of another side, a private or hidden side. The impression is of a life lived out in the open, where even hobbies like rugby league had a political or at least a social context – a context of devotion to a cause. The cause was changing the world.

*

Locke's biography is about a lot more than Bill Andersen. It is a record of the social and political attitudes of a vanished world. The prism we see this world through is the life of an unusual, controversial figure, a radical union leader deeply engaged in the big political and social questions of his time, from the 1940s through to the 21st Century. Bill was beyond the pale in respectable New Zealand society. He was accepted in his own blue-collar, male-dominated world not because of his communism but because of his practical leadership and integrity.

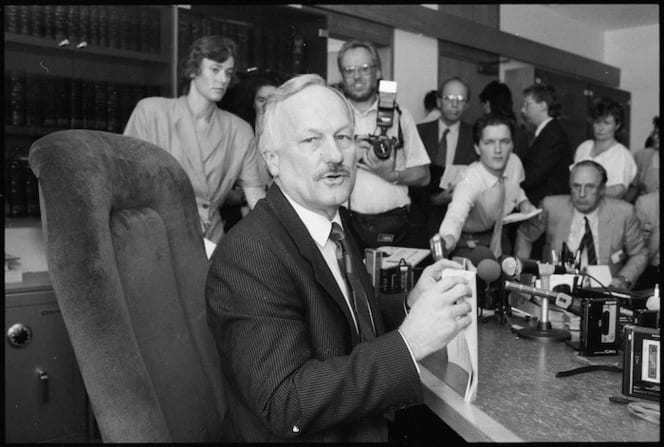

He came under immense pressure. Derided by the business-owning class and media, and even many of the working-class New Zealanders, he sought to represent, he was publicly denounced by Prime Minister Rob Muldoon in the 1970s. It didn’t appear to faze him. In what may have been an act of pre-internet trolling, Bill would regularly stand in general elections against Muldoon in his Tamaki electorate. The Socialist Unity Party didn’t get many votes, but Bill would come back with the line that Muldoon wouldn’t get many votes if he ran for the leadership of the Northern Drivers Union.

The Fourth Labour Government were liberal, feminist, and sympathetic to Māori aspirations, but ended up unleashing an unprecedented social disaster of inequality, advanced ferociously by the following National government

When this vanished world started to vanish, around 40 years ago, Andersen and Muldoon fell victim to the same forces of unregulated global capitalism that bulldozed through New Zealand. Both after all were products of their generation, their formative years spent in the era of economic depression and war. Despite National Party rhetoric about free enterprise, Muldoon operated a highly regulated protectionist economy, state-led development (‘Think Big’) and hands-on economic management. It is now established wisdom to mock all this, but the people doing the mocking didn’t live through the bad years of the 1930s and 1940s. The neoliberal coup (I don’t call it a revolution for obvious reasons) of the 1980s turned Muldoon from a feared bully into an historical embarrassment for a National Party now converted to free market ideology. His policies and war-generation conservatism were ridiculed, just as Bill Andersen’s old school Soviet-style communism was thrown into the dustbin of history.

The generation who presided over this transformation of New Zealand society during the Fourth Labour Government (1984–1990) were liberal, outward-looking, feminist, sympathetic to Māori aspirations, all about “freedom.” They also ended up unleashing the unprecedented social disaster of inequality, advanced ferociously by the following National government elected in 1990. Looking at this too closely would bring into question the entire direction of our society in the past 40 years, so the declining moral fibre of the young is identified as the cause of crime and dysfunction.

Reading Comrade, I kept coming back to this sense of the great tectonic shift in our society. The cover photo (from 1974) features a dapper Bill Andersen marching up Queen Street at the head of thousands – reportedly 20,000 – workers after his brief imprisonment for defying an injunction taken against the Northern Drivers Union (the judge responsible was Peter Mahon, later known for his role in the Erebus Inquiry). It is unimaginable that you could assemble a crowd that size these days for this type of cause, even when the population has probably doubled. Nothing is the same. The values of society might as well be a different planet. The mechanics of how our economic life works now, compared to then, are unrecognisable. A great deal of this biography is tied up with the minutiae of Bill Andersen’s union activities – the negotiations with employers, the relentless year in, year out struggle to incrementally deliver improved wages and conditions, occasionally livened up with a feisty picket or walkout. From these details, a picture of this other New Zealand is built up.

Gordon Harold (Bill) Andersen was born on the same day in 1924 that Lenin died. There was little indication of the direction his life would take. His formative years provide insight into his emotional and personal makeup, which seems to be quite straightforward as portrayed in this biography. His background was respectable; his family could be described as skilled working-class. His father was a Danish seafarer who jumped ship in Auckland in 1905 and established himself as a master mariner. The youngest of several children, Bill grew up in a non-political family that weathered the Great Depression better than some. He didn’t enjoy school and left, joining the Army in 1940 after lying about his age (he was 16.) However, he was dismissed after three months. By 1941 he became a fireman on a tug. This was tough work, feeding coal into the furnace. The death of his mother that year and the outbreak of war pushed him out in the world. He became a member of the Seamen’s Union and joined the Merchant Navy, serving aboard the legendary sailing ship Pamir. His first trip was delivering wool and tallow to San Francisco. The ship was lightly armed – there was a .303 rifle to shoot any mines they came across. Bill was seen as a troublemaker by the Captain and when he returned to New Zealand it was as a passenger; a theme was beginning to emerge in his relationship with authority.

Bill spent the rest of the war serving on British flagged merchant vessels sailing between New Zealand and the UK. In the port of Aden, he witnessed young boys employed in slave-like conditions. He put up with bad onboard conditions, the miserliness of the ship owners, the class hierarchy dividing officers and seamen. It created a burning sense of injustice that would carry him through a lifetime. He was involved in a wildcat strike, arrested by British military police on trumped up charges, tried in Algiers and thrown into jail. “Being locked up on your own 24 hours a day gives time to think about life, take stock of one's attitude, do regular exercises and plan about life after you get out,” he would later write in an unfinished memoir.

After his release he mixed widely with locals and other seamen. It was a transformational experience. He’d been reading Marx, and when he arrived in the UK joined the Communist Party of Great Britain in the port of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Returning to New Zealand after the war, he quickly found work on New Zealand ships and joined the Communist Party of New Zealand. The CPNZ was tiny but active. Bill clashed with the fearsome leader of the Seamen’s Union, Fintan Patrick Walsh, a former radical who had evolved into a domineering operator. Bill bounced between jobs on ships, the freezing works and the waterfront. All the while he was building his reputation as a communist and a unionist, which could lead to tense situations with employers, authorities and more conservative workers. By his mid-20s he had sailed across the Pacific, served in the Merchant Navy during the War, been in military jail, fraternised with many nationalities in ports around the world, worked in tough jobs, and made a name for himself as a communist militant. He had also married and started a family, with the first of three children arriving in 1951. But this was going to be a big year for other reasons as well.

*

The 1951 Waterfront Lockout was the most brutal and heaviest industrial struggle in modern New Zealand history and is still in living memory, although those who actually took part in it are now all but gone. Bill once again found himself in the right (or wrong) place, working on the Auckland wharves. The waterfront in those days was a big employer. Thousands of wharfies worked in physically tough, dangerous conditions in the pre-container era. Port towns were busy, rugged and had close-knit community and family ties with multiple generations working in the same industries. The Waterfront Union was big, highly organised and with a tendency to elect larger than life characters as leaders. The small communist element often achieved leadership roles due to their commitment and skills, rather than their communist views. Growing tensions led to the watersiders refusing overtime when their request for pay increases were turned down. A new National government was looking for a chance to re-establish employer power and the dispute quickly ramped up.

As a locked-out watersider and union activist, Bill was active in Auckland, working on clandestine publications. This was more risky than it might sound. The government activated wartime emergency regulations to ban free speech. Watersiders and their allies were prevented from holding public meetings or stating their case. It was even illegal to provide food to the families of locked out workers (although this was a bridge too far for some police officers who turned a blind eye). CPNZ member Dick Scott served as the watersider’s in-house journo and wrote a searing account of the struggle called 151 Days, and later a more measured reflection in his own autobiography. The lockout had a major impact on our literary culture – it features in literary works such as a backdrop in CK Stead’s novel All Visitors Ashore, and in a bitter poem by Hone Tuwhare (another occasional CPNZ member) about an attack by baton wielding police on a peaceful march of watersiders in Queen Street.

The watersiders and their allies were defeated. The new National government used the Cold War as a method of isolating the radicals. The mainstream labour movement was under the control of Fintan Patrick Walsh who was happy to see left-wing competition taken out of action. The Labour Party sat on the fence. A snap election following the lockout resulted in an improved result for the National government of Sid Holland, referred to by the wharfies as the Senator for Fendalton. Yet there was a strange side-effect. Many of the wharfies pushed out of the industry and blacklisted were young, energetic guys who re-established themselves in other industries, notably in Auckland. Dynamic characters, strong personalities, with strongly left-wing politics, they went on to form the backbone of blue collar unionism in New Zealand for decades.

Bill Andersen was one of them. He became a truck driver for Winstone Transport, an activist, a delegate, and after a few years and fights, an official of the Northern Drivers Union. Over the decades, the union would evolve through amalgamation. (By the time I worked for it in 1990s, it was the National Distribution Union, incorporating retail workers as well as drivers, warehouse workers and textile workers. In 2023, its direct descendant is FIRST Union, which covers an even greater range of sectors including finance sector workers.)

In the 1960s and 1970s Bill established a base in the Auckland union movement through steady work. He was aware his communism was holding back his career as a union official but declared he was not interested in ambition “in the bourgeois sense”. Part of the density of this biography is that there are two parallel lives in it – Bill Andersen the union leader, and Bill Andersen the communist. Bill was clear there was a demarcation between the two roles. But of course they influenced each other. In addition to the workplace struggles, Bill advocated political unionism and brought principled political arguments into the union movement – for the peace, anti-nuclear and anti-apartheid campaigns. The trials and tribulations of the communist left were often far more dramatic (on a minute scale) than the prosaic world of unions.

I didn’t meet him until he was into his 70s, when he was still working full-time as the NDU National President. He had stayed on after retirement because the union was struggling in the aftermath of the Employment Contracts Act

Over the post-war period through to the collapse of the USSR, communist parties in the Western world were splintering under the weight of their own ideological contradictions in a rapidly changing world. The revelations of the post-Stalin era shook the moral certainty of communism as the crimes and blunders of the Russian leadership were exposed: what made it worse was the tone of absolute unquestioning loyalty that had been the approach for so long, and unfortunately continued in some cases. The Soviet invasions of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968 alienated many supporters of the general cause. Even the Communist Party of Australia spoke out against Czechoslovakia, but Bill and the Socialist Unity Party refused to criticise. The upsurge of social struggle in the 1960s largely bypassed the established communist parties in favour of the 'New Left'. Good or bad, Communist positions were often at odds with conservative attitudes, including those within the unions.

One example is Bill’s strong support for Māori political causes. He was involved in the occupation of Bastion Point and at the very end of his life he also joined the hikoi against the Foreshore and Seabed Act. He formed strong relationships with Māori in the union movement and engaged the NDU in these campaigns. One leading Māori unionist Syd Keepa is quoted in Comrade on how he felt that Bill had absorbed views Syd had shared on Māori society and culture – which added something to his Leninist ideology.

The militant image was a contradictory one when it came to Bill. I didn’t meet him until he was into his 70s, when he was still working full-time as the NDU National President. I didn’t realise at the time, but according to Locke, he wasn’t getting paid apart from his state pension. He had stayed on after retirement because the union was struggling in the aftermath of the Employment Contracts Act. He was the opposite of the loud-mouthed bloke. Tall, dignified, low-key, he was in an old-fashioned way a genuine “people person”. He was a big man, who kept in good shape. He dressed quite formally. He had two tattoos on his arms – one in memory of his mother and one of the Pamir, the ship he first sailed on as a young man.

There was a sense of steel underneath the amiable exterior as well. He had often been in the thick of it in quite heavy pickets. I recall going out with him to a dispute in South Auckland. There was a large crowd of staunch union members – mostly young Māori and Pacific guys. It was a different world to the provincial South Island one I had emerged from. I wondered how this dry old Pākehā guy would come across. But of course Bill had been active for decades in Auckland in all manner of struggles. He was listened to with great respect, and later when I walked with him back to the car some of those young guys were coming up to greet him. I got a sense of his mana.

This appreciation was not shared by all. Bill’s high profile meant he became the target of an orchestrated hate campaign in the 1970s and 1980s. It started with public attacks in the media but escalated to more sinister extremes. He received death threats, which he and the police took seriously. The violent rhetoric of the post-Covid era is not some aberration. It is part of a long tradition in New Zealand society – the dark side to the stereotype of the gruff but good-natured Kiwi bloke (as a cliche, it is generally a bloke). Political violence in New Zealand has largely been the preserve of the state (in 1951 or the 1981 Tour for example, or the French government in the Rainbow Warrior bombing) or the extreme right (the Trades Hall bombing of 1984, which was obviously politically motivated.)

Of course, Bill was not popular with all other communists either. Unity and collectivism are common terms on the left but leftists often reserve their real venom for those closest to them. Because of his approach and affiliations, more radical and younger activists saw him as a controlling bureaucrat who specialised in dampening down the class struggle. The schemings and schisms within New Zealand Marxism detailed in this book are fascinating. It’s depressing how intelligent and self-sacrificing people can lose sight of the bigger picture. One can see how it could end up in grim conclusions in bigger, meaner settings. For all this, in the local context communism represented a reply to the exploitation and dull certainties of mainstream political and economic life. It is common these days for sophisticated modern commentators to refer to communism as being essentially religious. This is meant in a perjorative sense. In our intellectual culture, a tone of superior irony wrapped around self-interest is the preferable stance. But it is also an inaccurate accusation. Bruce Jesson once wrote there were lots of nutcases in the New Zealand communist movement, but there were also lots of very good people. Once you cut away the absolute error of falling into line behind the power politics of Stalin-era Russia, the actual work on the ground that communists (and socialists) did around local issues and local campaigns had a positive impact well beyond their numbers for working New Zealanders.

*

Locke goes into some detail about these matters. In a sense, this biography is also one of the best accounts I have read of the long and gruelling ideological journey of New Zealand communism and its relations with the wider left. A big split in the CPNZ occurred after a majority faction declared support for Mao’s China over the Soviet Union. Bill, along with a number of communists in the Unions, departed and formed the pro-Soviet Socialist Unity Party in 1964. Ken Douglas, later the CTU President, was another SUP comrade at the time – he and Bill would later have a bad political and personal split in the late 1980s. Further division followed. In Rebecca Macfie’s biography of Helen Kelly, she describes when Helen’s parents Pat and Cath Kelly abandoned communism after various splits and expulsions and finally joined the Labour Party. Their friend, the late Seafarers’ Union President Dave Morgan left the CPNZ after what he described to me once as another “lemming-like decision” of the party, although he claimed to remain a revolutionary socialist to the end.

Bill’s last political effort after the collapse of the Soviet Union was the somewhat boutique scale Socialist Party of Aotearoa (SPA). I helped him print their originally titled newsletter Red Flag once or twice, out of personal respect. I have a copy of a booklet written by Bill and produced by SPA that deals with the 1996 election, calling for the political left to work together. It is matter of fact, earnest and a little dull. It was not what I would call a visionary blue-sky document. There is nothing wrong with this, especially when some current day Marxism has morphed into a navel-gazing academic speciality. Nonetheless, the mid-20th Century Stalinist environment of the communist parties did not encourage a lively, open intellectual culture. The subservience to overseas party lines, the failure of internal democracy, the degeneration that comes with small and shrinking organisations in a hostile environment, all worked against them. Their ideas either became more and more pedestrian and compromised, like the Socialist Unity Party, or more and more crazy, like the remaining fraction of the CPNZ which eventually abandoned China and became enamoured with Albania under the leadership of Enver Hoxha (it then fell in with the Trotskyists after the collapse of the USSR, before falling out with them again). I was discussing politics with Bill once and mentioned Noam Chomsky – Bill looked mystified. He had a life time of knowledge and experience of communist activism, but he was not familiar with one of the leading left-wing thinkers of the modern age. By the time I got involved in union and socialist politics in the 1990s, it all seemed a festering mess of decades-long feuds. Sorting out the various factions was just about a full-time job in itself. This all came back to me when reading Comrade, even though I was on the outskirts of this world. The 1960s and 1970s saw an upsurge in workers' struggles and social turmoil, but the 1980s had ended with the disaster of the Fourth Labour Government. On the world stage, extreme capitalism was running rampant, the Soviet Union had collapsed, and the “end of history” was declared – even China was adopting market methodology. This all hastened the dissolution and degeneration of the political left. The remaining groups turned on themselves even more ferociously. The problem with the hoary old Monty Python joke about the “Peoples Front of Judea” versus the “Judean People’s Front” is too close to the bone. Yet this corrosive negativity was not limited to the Marxist left. In the 1980s and 1990s, the mainstream of the unions and Labour Party politics were dragged through the Rogernomics era and subsequent fallout, most notably the split in the Labour Party that led to the formation of the NewLabour Party in 1989 and then the Alliance shortly afterwards.

The attitude of the Labour Party was National was the competition but the Alliance was the enemy. Which was reasonable, since the Alliance’s goal was to replace the Labour Party from the left – and in my view, the tragedy is that it did not do so. To complicate matters more, there were two non-friendly trade union groupings in the 1990s, the CTU and the more edgy TUF, a situation that somewhat mirrored the Labour/Alliance scenario. Some unions belonged to neither. Bill Andersen had years of experience as a communist operating in a Labour Party-dominated union movement and tried to act as a mediator. He urged the left wing of Labour and the Alliance to co-operate, although given the way the communists carried on this was probably a bit optimistic. It is strange to think about this era of loud and fractious disagreement now, because the union movement is so different these days. As with the political wing of the Labour movement, the centre/right faction won. The militants and the left have either disappeared or adapted themselves to the new era (in my own small way, I would include myself in this category.) It is much more pleasant because there is little to seriously argue about anymore, just some occasional grumbling with like-minded souls. But the union movement has lost an ideological tension required to produce a vital movement. Just as too much division leads to disunity and defeat – the great fear of ‘51ers like Bill Andersen – the opposite situation of bland homogeneity is also a dead end.

Unemployment and inequality have become a feature of New Zealand life, ignored, accepted or regarded as the result of the personal failings of low-quality people

The late 1980s and 1990s is the third and final act of Bill’s political life detailed in Comrade. The fallout of Rogernomics – that monumental betrayal by politicians who built their careers in the worker’s party then ripped apart the working class. It was not a great time. The new National government elected in 1990 followed up with the Employment Contracts Act and benefit cuts. Unions went into free fall. Unemployment soared and poverty and inequality became entrenched: they have become a feature of New Zealand life, ignored, accepted or regarded as the result of the personal failings of low-quality people.

Interestingly, the prime minister at the time, Jim Bolger, seems to have a bad conscience about it all, and in recent years has basically admitted things went too far. I’m glad to hear it, but the absolute contempt the unemployed and struggling were shown at that time by his government is not something I find easy to forgive. They were sacrificed, but what for? The promised economic wonderland never arrived – or if it did, for a privileged minority. Throughout these tough years, the NDU struggled. Union membership collapsed, as was the intent of the Employment Contracts Act that provided the legal machinery for aggressive employers to smash their workforces into compliance. The pressure was on and the financial viability of the union was getting close to the line. Solid relationships fractured. Old comrades fell out. There was a lack of new leadership and succession planning. Bill’s ongoing presence was not appreciated by all in the movement. But the union fought on; it survived, it evolved and it eventually recovered somewhat, but without Bill, who died in 2004, after a short illness. He never retired.

In the years since his death, global capitalism has gone through two major crises, the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the Covid pandemic. Despite worsening inequality, in the developed world there has not been a shift to the left. Functioning communist parties still exist in some developed countries such as France and Italy, and curiously, also Japan. The Russian Communist Party is still going, as a travesty of muzzled opposition in Putin’s state (the leadership backed the invasion of Ukraine). In Europe, there are left and socialist parties that often incorporate communist factions, such as Die Linke (The Left) in Germany. There have been radical upsurges such as in Greece (quickly neutralised). Even the brief and tantalising promise of social democrats like Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn faded away. Radicalism is now the preserve of the far right, or the conspiracy right, and is in rude health in Europe, the UK and the United States. In the USA, it now seems to have effective control of the Republican Party. Liberal capitalism is being challenged from the far right, rather than the left.

One of the weirdest developments is the emergence of China as a world power under a supposedly Communist Party leadership. Elsewhere, communists seem to be all over the place as to what this means. No one really knows. Obviously modern China is not communist in any sense proposed by Karl Marx, even if his picture is still up on the wall at party conferences. It is pursuing a different form of state-dominated, capitalist development under an authoritarian one-party state that claim this is “socialism with Chinese characteristics”. One irony is how some of the biggest friends of Red China in New Zealand are no longer communists, but current and former National Party politicians operating in the business elite, including Jenny Shipley, Judith Collins and more recently Sir John Key, who has publicly promoted China in think pieces in the media. Right-wing, run of the mill voters often hold anti-Asian prejudices and rave about communist takeovers, yet the right-wing ruling class are busy doing deals with the communist entrepreneurs.

In her preface, Cybèle Locke notes a “key principle” in the life of Bill Andersen – “No matter how difficult the balancing act, a trade union leader should always have a communist party at their back.” There are no real communist parties in existence as such in New Zealand these days. Bill’s last project, SPA, vanished. There are various small Marxist groups, often with a Trotskyist or “decolonisation” angle, that lurk on the fringes of campus life. I belong to the Socialist Society, which is more a heterogenous discussion group. There are quite a few socialists left in the unions. They often end up as delegates or organisers but are rarely allowed near the controls. Unionists with a more career-minded bent can get selected as Labour Party candidates. They join a liberal organisation dominated by urban professionals who have not done too badly out of modern day capitalism, even if they feel a little queasy about some of the side effects. Apart from vague references to kindness there is no real coherent set of principles behind the Labour Party. Some argue this is why it is successful – it's a broad church moving with the times, bringing together diverse groups to create practical solutions in a pluralistic democracy. An opposing argument is that it is fully co-opted into managing the system it was specifically set up to replace a century ago.

It would be unfair to entirely blame the Labour Party for this situation. Global capitalism has had a similar effect on politics everywhere. Anyone who steps out of line is quickly subject to market discipline, which is the real locus of power in modern politics – not a bunch of MPs yapping and smirking at each other in Question Time. The unfortunate tribalism of New Zealand politics means you can’t mention these things. The Labour Party people see any criticism as doing the work of the National Party. The Labour-affiliated unions tell themselves the Labour Party is theirs – they started it, after all, as the political wing of the labour movement. But this is not true. The unions are effectively a formalised lobby group who get a hearing because the Labour Party needs their votes and money. They do get a few wins, but it doesn’t have a significant effect on the direction of our society. As a mirror image, Tory media hacks rant about the union-dominated Labour Party, but this is equally nonsense. After all, the employers, property people, financiers and big farmers have the ear of the National Party, and have been far more successful than unions in remodelling our economic system to serve their class interests.

These days, with the development of the far right that links a hard core of rural reactionaries with the conspiracy crowd, you get even more wacky accusations being thrown – Jacinda Ardern accused of being a communist dictator. I wonder what Bill would have made of that. Much of this political derangement can be put down to the demented influence of American politics and culture in an age of digital social media, but is also due to the disappearance of the kind of mass political consciousness (however limited) of a union movement and genuine left parties. In New Zealand, there is no coherent, rational socialist alternative to make the case for a different path. We are the worse for it.

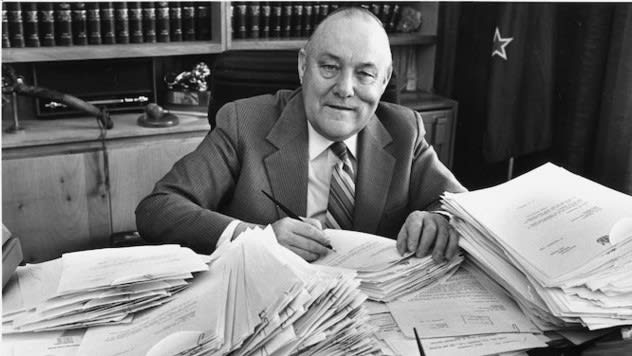

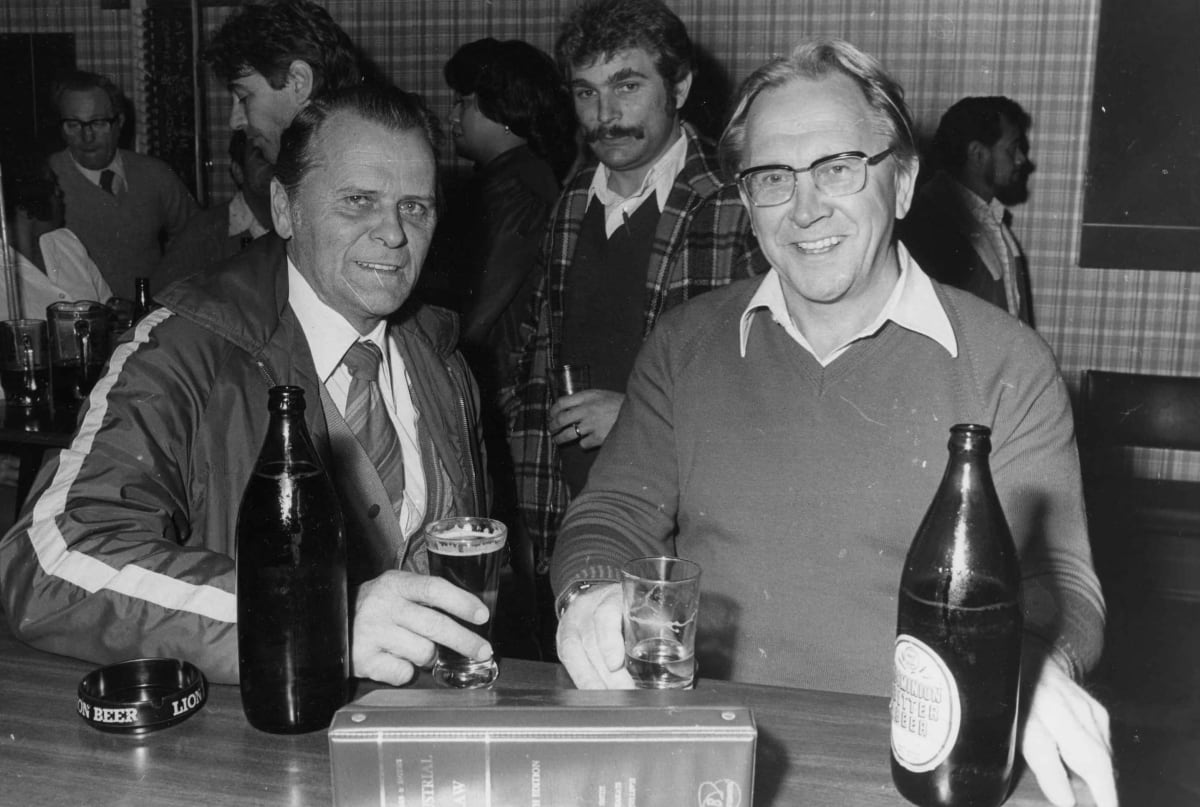

With Comrade, Cybèle Locke has produced a definitive biography of one of the most interesting, principled public figures of 20th Century New Zealand. She has packed a vast quantity of research into this book, and has consulted and interviewed an exhaustive list – a genuine who’s who – of the unions and the political left. It has been a work that has taken years but the result shows. Her narrative is always in context and gives a true sense of the unfolding of the social and political events Bill Andersen was always in the thick of. Just flicking through the photos provides an evocative time capsule into that vanished world, a world where a communist union leader could walk up Queen Street with 20,000 grizzled-looking factory workers who have got his back.

My own lasting memory of Bill was him coming into my office at the NDU in the late 1990s. He’d lean against the big printing machine we did the union newsletters on, cross his arms and have a yarn, standing in the afternoon sun that would come in from the big windows looking west. His brand of communism was finished. The unions had been hammered by the Tories and we were against the wall. But he never seemed despondent and remained philosophical, just getting on with it, like the young guy who spent his time in an Algerian lockup 50 years before thinking about his place in the world. Bill always had time for workers. I was just a young guy who did the newsletter but he was always interested to see how things were going for me. He was a decent human being, and a leader who served his class to the best of his ability. This biography serves his memory well.

Comrade - Bill Andersen: a communist, working class life, by Cybèle Locke (Bridget Williams Books, $50) is available in bookstores nationwide.