Nearly two-thirds of U.S. households have at least one pet. More than ever before, companion animals are a part of life – particularly in cities, where the majority of Americans live.

Cities offer access to many resources, but often it’s not distributed evenly. Some scholars describe parts of U.S. cities with few or no grocery stores as food deserts. Others have identified zones they call transit deserts, where reliable and convenient public transit is scarce or nonexistent.

While the “desert” framing is controversial, there is little disagreement that access to goods and services in many U.S. cities is unequal. I have studied urban animal welfare issues for the past 15 years, and I have found that the inequities and economic stress humans face affect animals as well.

Recently, University of Nebraska geographer Xiaomeng Li and I explored access to animal welfare services in Detroit. We found that pet resources were significantly more likely to be located in ZIP codes with more highly educated residents, higher incomes, fewer children under 18 and higher median rents.

If households with pets were located mainly in these areas, it would make sense for pet resources to be similarly concentrated. However, while many Detroit households own animals, some parts of the city offer much more access to basic pet supplies and care than others.

Pets come with costs and benefits

Detroit had 639,111 residents as of 2020. Assuming that pet ownership in Detroit resembles the national average, nearly two-thirds of its 249,518 households would have at least one pet, which would total just over 157,000 companion animals in the city.

Detroit is more economically distressed than the U.S. overall, with a median household income of $36,140, compared with the U.S. median of $67,521. Nearly one-third (30%) of Detroit residents are in poverty, compared with 11.4% nationwide. Racial segregation and income inequality are also high.

Detroit’s well-publicized economic and fiscal struggles undermine the city’s ability to provide services, including animal care and control. Other factors, including housing vacancy and abandonment and a high number of stray and feral dogs, add to the animal welfare challenge.

Still, there is good reason for Detroit and other cities to support pet ownership. Studies show that having companion animals in the home boosts human mental and physical well-being. Dog owners report getting more exercise than non-dog owners. And surveys conducted during the pandemic suggested that animals reduced the stress and anxiety of lockdowns.

Mapping pet care resources

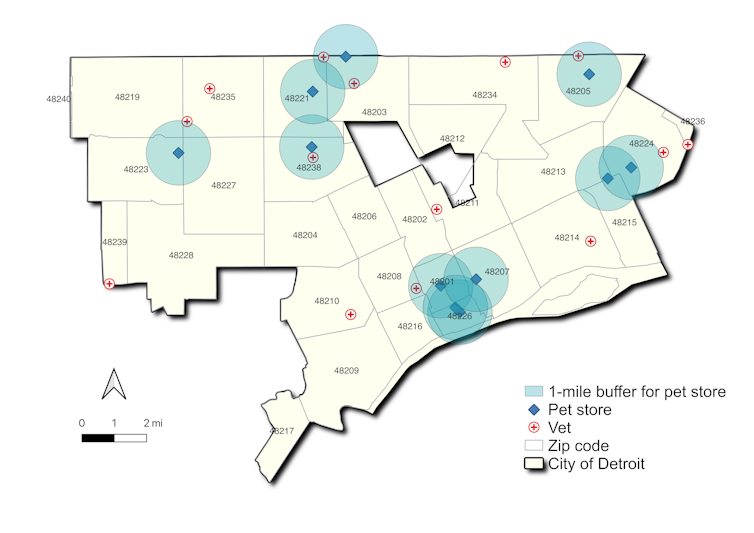

For our analysis, we compiled data on locations of pet stores and veterinarians from the ReferenceUSA Business Historical Data Files and Google Maps. We combined it with census data to see how pet resources correlated with the demographic characteristics of Detroit ZIP codes. We also mapped demand for animal support services, which we defined as dog bites and animal cruelty cases, in each ZIP code.

Our main finding was that Detroit has few dedicated pet stores and veterinary clinics, and these resources are not evenly distributed. Eleven of the city’s 26 ZIP codes, clustered in contiguous areas, have no pet stores or vet clinics. They form two large areas: a band stretching across the mid-city, and a zone in southwest Detroit.

We identified 11 specialty pet supply stores that serve Detroit’s 243,000 households. Four of these stores are in the downtown/midtown area – which, due to gentrification, has an increasing number of younger, white and higher-income residents.

The other seven stores are scattered around the periphery of the city. This distribution leaves a large underserved area in between, with many residents living a mile or more away from a pet store.

Veterinary practices are not clustered in the same way. While there are very few vet offices relative to our estimated number of pets, these offices are spread relatively evenly across the city and are more likely than pet stores to be located in middle- or lower-income ZIP codes.

Overall, we found that Detroit ZIP codes with more young, single and highly educated residents and higher median rents have significantly more pet resources per capita. More densely populated areas – such as Mexican Town, with high numbers of Hispanic residents, and the city’s far east side, with a high proportion of African Americans – have significantly fewer.

Overtasked animal shelters

Lack of access to pet food and supplies is a problem in low-income areas, even in the age of online providers such as Amazon and Chewy. Shopping online requires internet access and credit card payment. People who can’t mail-order pet supplies need physical access to stores.

There’s no official data source on Detroit’s pet abandonment rates, but the city has a long-standing and significant stray dog problem.

In 2022, the four largest animal shelters in Detroit took in 7,095 dogs. For comparison, Animal Rescue League shelters in Boston, which has a similar population size, took in 1,049 dogs in 2019.

The collective 2022 dog euthanasia rate for the four Detroit shelters was about 22%, although it varied widely among the shelters. Animal shelters that are designated “no-kill” generally aim to euthanize no more than 10% of the animals they take in, and to do so only when irreparable health or behavioral issues prevent the animals from finding new homes. Detroit Animal Care and Control, a city agency, regularly operates beyond capacity and has to euthanize animals due to lack of space.

Having ready access to pet resources could encourage Detroit residents of all income levels to adopt pets and help prevent relinquishment to shelters.

Getting more help to pet owners

Encouraging more pet-related businesses to open in distressed and underserved areas is an economic development challenge. Small-business incubators could support prospective pet store owners and vets who are open to locating in lower-income areas. These organizations typically provide locations for new businesses, offering below-market rents, startup capital and small revolving loan programs.

Incubators are generally run by local governments or public-private partnerships. These organizations could use incentives funded by local taxes to attract businesses in the pet care sector.

Community programs also have a role to play. In high-poverty areas, simply educating people about what kinds of resources are available is a useful starting point.

Many national organizations have programs to help pet owners who are struggling financially. For example, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals provides services in underserved communities, including low-cost veterinary care, supplies and information. Other nonprofit organizations operate mobile veterinary clinics that provide services in areas of need.

In Detroit, organizations such as Dog Aide and C.H.A.I.N.E.D., Inc. provide resources for pet owners, including pet food, outdoor housing, fencing, medications such as heart worm pills and flea preventatives, and low-cost spay and neuter services.

Many food banks and pantries provide free food for pets – an especially effective way to help both animals and humans. Some home delivery programs, such as Meals on Wheels, partner with pet suppliers to bring pet food and medications to elderly and disabled clients.

Supporting humans and their four-legged companions can promote human and animal health and reduce pressure on animal shelters. Our research shows that cities like Detroit, where many people are financially distressed and don’t have easy access to transportation or online shopping, can meaningfully improve residents’ lives by helping them meet their pets’ basic needs.

Laura A. Reese is president of Professional Animal Welfare Services, a consulting firm focusing on animal welfare issues and management best practices. She is a co-founder and board member of the Un-Shelter, a nonprofit that works with other animal rescue groups to foster and find homes for strays in metro Detroit and Washtenaw County, Michigan, and has volunteered with other Detroit animal welfare organizations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.