Driving on the A57 near Sheffield with girlfriend Miriam Barendsen on New Year’s Eve 1984/85, Def Leppard's Rick Allen lost control of his black 1984 Corvette Stingray and hit a brick wall. His seatbelt came undone and took off his left arm as the drummer was thrown through the sunroof.

After being told he wouldn’t play again, Allen began a lengthy recovery programme that culminated in his return to the stage in August 1986. This is the story of how he got there.

Coming round in hospital after my accident, I was told that I would be there for at least six months but I had a lot of visitors including Mutt Lange, our producer, who lit a fire under my ass, and some Hare Krishnas who brought really healthy food each day. In the end I left within a month.

I’ve since learned that certain people asked the band, ‘You’re not going to let the freak show play with you onstage, are you?’ Fortunately, I didn’t hear any of that. All the same, I was regularly told that I would never play drums again and it wasn’t until Steve Clark and Phil Collen came to see me that I began to really believe otherwise. They were both so friggin’ drunk but I had been practising on a big piece of foam at the bottom of the bed, and with the help of a guy called Pete Harley, who made me an electric kit and is now sadly no longer alive, I learned to play again.

Getting back to a place where I could re-join the band had been a very tough process. At first even walking was a trial, but I locked myself away in a room at my parents’ house in Dronfield and just played and played. There were times when I thought I just couldn’t do it and wanted to curl up into a ball and give up. But I persevered.

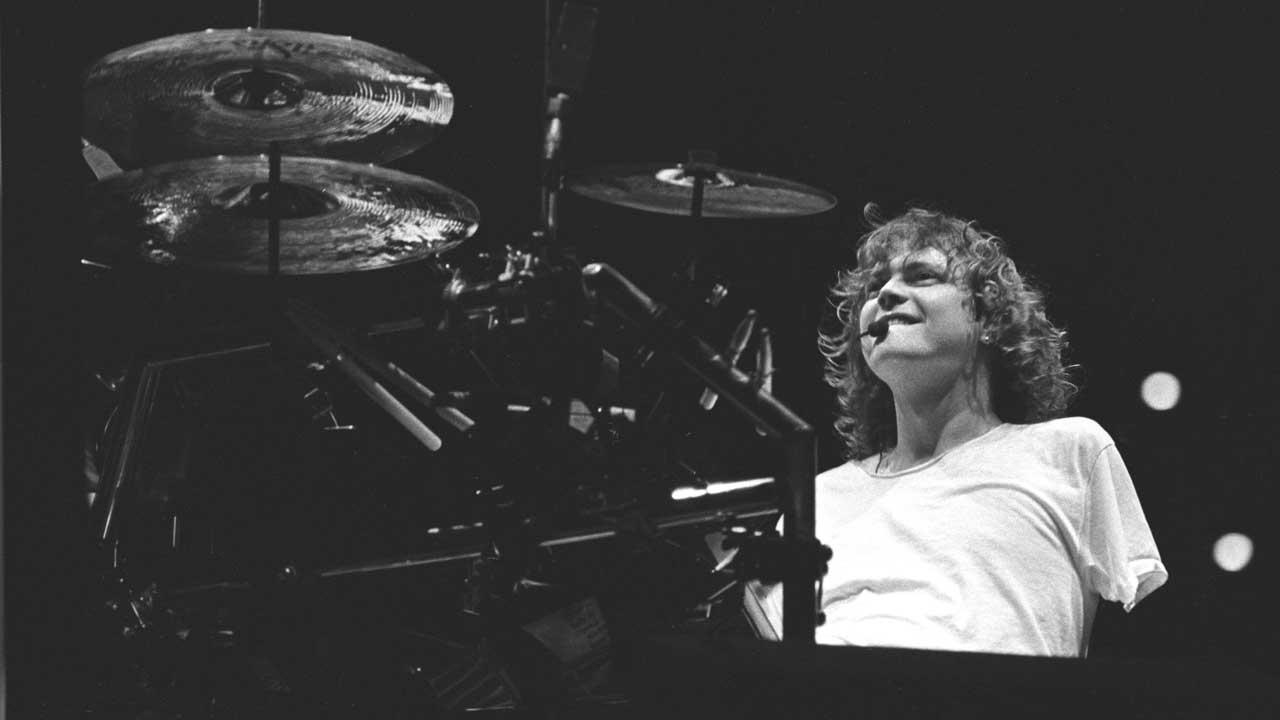

We were scheduled to play Monsters Of Rock at Castle Donington on August 16, 1986. The band had already played three Irish warm-up gigs with Jeff Rich helping out on an acoustic kit, purely as a safety net. Jeff missed his flight for the fourth gig and I played half-a-dozen songs on my own before he showed up. At the next gig the stage wasn’t big enough for two kits so I did it alone. Afterwards Jeff said: “I guess I’m going home tomorrow’.” I did the next one, in Dublin, alone as well.

But on the day of Monsters Of Rock, it felt quite surreal. I was nervous, but I knew that I was capable of doing this. Backstage, it felt strange to be the centre of attention. Everyone from Ozzy to the Scorpions came by to wish me well and offer encouragement. Everybody was on board and knew that what was happening was unique, I felt overwhelming support. Joe Elliott and I stood in a backstage trailer and drained the better part of a bottle of whiskey between us. Nearer show-time the bubble burst. I realised that this would either be great or a complete trainwreck.

Before the show we had decided to treat it like just another gig, but without getting too cheesy, there was a vibe of overwhelming love, and I knew within a number or two that it would be fine. There was a groundswell of energy from the audience, willing Joe to say something. He had no choice. When he introduced me so beautifully, and the roar of the crowd was so loud, I burst into tears. I thought, ‘Shit… if I cry on these pedals will I get electrocuted?’ Thirty years on, that day remains in the top five moments of my life. Each time I’ve returned to Donington I’ve realised that it saw me become a man.

What I didn’t realise was that the fall-out left issues to deal with. I really should have taken the offer of counselling, but I was stubborn. There was also a darker side. Recording the Hysteria album in Holland – and Amsterdam in particular – led me down wrong paths. I started self-medicating and discovered some interesting drugs.

I now know that post-Donington was when the real work began in putting myself back together. That’s why to this day I do a lot of work with the military. My own trauma wasn’t combat related, but I have learned a lot from solders and hopefully they learn from me as well. And of course I will always remember that very special day.