In March, the United States imposed new sanctions on eight Zimbabwean individuals, including President Emmerson Mnangagwa and his wife, and other officials, following allegations of corruption and human rights abuses. It also placed sanctions on three businesses – also because of alleged corruption, human rights abuses and election rigging.

A statement from Mnangagwa’s office described the accusations as “defamatory”. It added that they amounted to a “gratuitous slander” against Zimbabwe’s leaders and people.

The move came after a review of US sanctions which have been in place since 2003. From now on, sanctions on Zimbabwe will apply to individuals and businesses listed under the Global Magnitsky Act of 2016. This Act authorises the US government to sanction foreign government officials worldwide for alleged human rights abuses, freeze their assets, and ban them from entering the US on unofficial business.

By switching to the Magnitsky Act to cover sanctions in Zimbabwe, the US said fewer individuals and businesses will receive sanctions than have until now. “The changes we are making today are intended to make clear what has always been true: our sanctions are not intended to target the people of Zimbabwe,” Deputy Treasury Secretary Wally Adeyemo said.

Rutendo Matinyarare, a vocal government supporter who leads the Zimbabwe Anti-Sanctions Movement, welcomed the change to the sanctions regime. “The real sanctions are gone now, so no more excuses. Let’s build the country now,” he tweeted on X, formerly Twitter.

𝐍𝐎 𝐄𝐗𝐂𝐔𝐒𝐄𝐒. 𝐋𝐄𝐓’𝐒 𝐍𝐎𝐖 𝐁𝐔𝐈𝐋𝐃.

The real sanctions are gone now, so no more excuses. Let’s build the country now.

The sanctions on the President, VP, First Lady, Minister of defense and our amazing business people should be fought through the best legal minds… pic.twitter.com/BQAysQlRdc

— Rutendo Matinyarare (@matinyarare) March 8, 2024

Why does the US impose sanctions on Zimbabwe?

The US says it aims to promote democracy and accountability and address human rights violations in Zimbabwe.

“We continue to urge the Government of Zimbabwe to move toward more open and democratic governance, including addressing corruption and protecting human rights, so all Zimbabweans can prosper,” David Gainer, the US acting deputy assistant secretary of state said.

The US is also the largest provider of humanitarian aid to Zimbabwe, providing more than $3.5bn in aid from the country’s independence from British colonial rule in 1980 until 2020.

Do sanctions harm Zimbabwe’s economy?

Last year, Zimbabwean Vice President Constantino Chiwenga said the country had lost more than $150bn because of sanctions imposed by the European Union and the United States.

Alena Douhan, UN Special Rapporteur on unilateral coercive measures, who visited the country in 2021, said the sanctions “…had exacerbated pre-existing social and economic challenges with devastating consequences for the people of Zimbabwe, especially those living in poverty, women, children, elderly, people with disabilities as well as marginalised and other vulnerable groups”.

A 2022 Institute of Security Studies Africa (ISS) report found that investors tend to steer clear of Zimbabwe because of the “high-risk premium” placed on the country due to the targeted US sanctions.

Some international banks have also cut ties with Zimbabwean banks because the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) penalises US companies or individuals who do business with any sanctioned individual, entity or country.

Are sanctions the only thing holding back the economy?

Zimbabwean economist Gift Mugano said that corruption, even more than sanctions, holds Zimbabwe back. “Zimbabwe can weaken the possible effects of so-called sanctions, but corruption is the major problem,” he told Al Jazeera.

He added that the US and others have never imposed trade sanctions on Zimbabwe. “We can trade with anybody, including the Americans and the Europeans; the measures were financial and didn’t affect trade.”

Eddie Cross, an economist who advises the government and has written a biography of President Mnangagwa, pointed to Transparency International figures showing that corruption has cost Zimbabwe $100bn since independence. “That’s more than $2.5bn a year, but combining the two [corruption and sanctions] is enormous.”

However, the US still operates the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act (ZIDERA), which the Congress passed in 2001. While the US says this is not a set of sanctions, ZIDERA prevents Zimbabwe from accessing loans and investment from international financial institutions, such as the IMF and the World Bank, which experts say hampers its ability to develop economically. Some institutions had stopped lending to Zimbabwe before ZIDERA because of its poor record of servicing loans.

Cross said experts estimate that banks lose about $1bn annually in higher bank charges because of ZIDERA. “ZIDERA has been in place for 23 years, and a billion dollars a year could have easily settled our national debt.” He added that the additional costs arise when local banks go through banks other than the regular correspondent banks, which sometimes refuse to deal directly with Zimbabwean banks for fear of being penalised by the US government.

Among the conditions Zimbabwe has to meet for the repeal of ZIDERA is the restoration of the rule of law, the holding of free and fair elections, a commitment to equitable, legal and transparent land reform – including the compensation of the former farmers who lost their land to the country’s land reform programme – and the military and police withdrawing from politics and government.

Do sanctions work?

Cross argued that sanctions do not tackle corruption. He questioned why the US does not impose sanctions on countries like China, which he says is undemocratic. “They allow China free access to international financial markets, Western technology and international markets, and they allow China to borrow enormous sums of money at very low interest rates with which they have been developing their infrastructure and economy.”

Additionally, a 2022 Institute of Security Studies Africa (ISS) report concluded that sanctions have largely failed to improve democratic behaviour among the ruling elites in Zimbabwe. Human rights violations persist and political freedoms remain severely curtailed.

Amnesty International regularly highlights the threats to freedom of expression, arrests of journalists and harassment of members of the opposition by security forces and members of the ruling ZANU-PF party.

Furthermore, an Al Jazeera investigation last year found Zimbabwe’s government was using smuggling gangs to sell gold worth hundreds of millions of dollars, helping to mitigate the effects of sanctions. Gold is the country’s biggest export, and gold trade itself doesn’t face sanctions. But the taint of broader sanctions against government officials makes it harder for the country to access the dollars it needs for international trade. That makes gold smuggling a valuable source of dollars.

Who else imposes sanctions on Zimbabwe?

The United Kingdom and European Union also imposed similar sanctions on Zimbabwe, giving the same reasons as the US. They have whittled down the measures over the years.

However, as of February, an embargo on the sale of arms and equipment that the government may use for internal repression remains in place. The EU and UK also still freeze assets held by state-owned arms manufacturer, Zimbabwe Defence Industries.

What do Zimbabweans think of the sanctions?

Members of the Broad Alliance Against Sanctions have been camped outside the US embassy in Harare since 2019, demanding an end to all sanctions, including ZIDERA.

Sally Ngoni, a leader of the group, said: “All these measures are a tool to effect regime change in Zimbabwe; they want our government to fail; it’s punishment for reclaiming our stolen land from the whites.” She was alluding to the sometimes violent fast-track land reform that saw white farmers lose their farms ostensibly for the resettlement of landless Black people launched in 2000.

However, other Zimbabweans support the sanctions, saying they should remain in place until the government stops harassing and silencing opposition figures. “The measures affect those listed and not the generality of Zimbabweans,” Munyaradzi Zivanayi, an unemployed graduate, told Al Jazeera.

Some believe removing sanctions would help to expose government deficiencies. “The removal of all sanctions will expose the government’s incompetence as they cannot use the sanctions as an excuse any more,” said Harare accountant Joseph Moyo.

How have Zimbabwe’s leaders responded to sanctions?

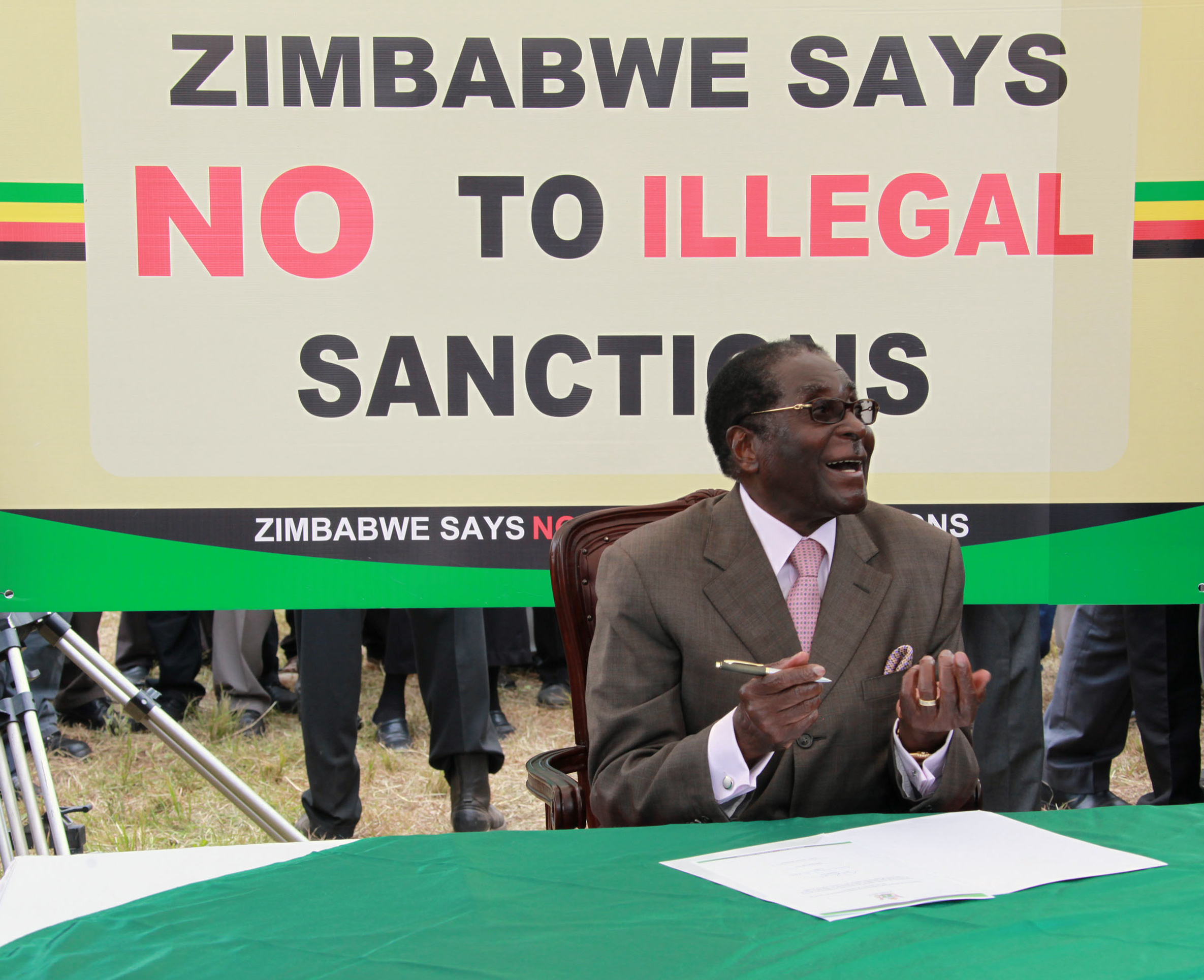

The late President Robert Mugabe called sanctions an “interference in the affairs of Zimbabwe,” a sovereign state. In response, he declared a “look East” policy, meaning Zimbabwe would strengthen economic ties with countries such as China and Russia, which he regarded as more supportive. He also forged stronger ties with other sanctioned countries, including Belarus and Iran.

After the military removed Mugabe in 2017, Mnangagwa, the new president, adopted a “friend to all and enemy to none” approach. This saw the new government vigorously pursue re-engagement with estranged countries.

In 2019, it paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to Ballard Partners – a lobbying firm run by a Trump campaign fundraiser – after the US government renewed sanctions on 141 individuals and entities, citing continued human rights abuses and corruption.

Despite this charm offensive, it is still US policy that Zimbabwe has not addressed the issues for which sanctions were imposed. Besides corruption, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, in a statement announcing the new sanctions, noted: “Multiple cases of abductions, physical abuse, and unlawful killing have left citizens living in fear.”

How have sanctions affected Zimbabwe-US relations?

Sporadic verbal outbursts, accusations and personal attacks characterise the complicated relationship between the two countries.

They took another hit in February when the US protested against the deportation of United States Agency for International Development (USAID) officials and contractors.

Zimbabwe’s version of the incident is that the four individuals entered the country without notifying authorities and held “unsanctioned covert meetings”. The Sunday Mail, a state-controlled weekly, reported that the meetings were held “to inform Washington’s adversarial foreign policy towards Zimbabwe”.

The US asserted that the USAID personnel were in the country legally and that the Zimbabwean government knew of their presence and mission.