They are a group often overlooked, described as “invisible”, or perhaps assumed not to exist at all.

There is no reliable data that captures the number of LGBTQ+ Australians with intellectual disability. But in 2020, Australia’s largest national survey on the health and well-being of LGBTQ+ people found more than one-third (38.5%) of the 6,835 respondents had a disability or long-term health condition.

People with intellectual disability face additional barriers to access and participation in community, which means their voices are often missing from LGBTQ+ events, in government consultations, and in disability spaces.

We partnered with Inclusion Melbourne and Rainbow Rights & Advocacy, an advocacy group of LGBTQ+ people with intellectual disability to hear about what mattered to them, and what they wanted other people to know.

‘Include us’

We spoke with dozens of LGBTQ+ people with intellectual disability over hundreds of hours.

We did this work alongside peer researchers: LGBTQ+ people with intellectual disability who facilitated the online group and individual sessions and co-created the research resources.

We asked how LGBTQ+ people with intellectual disability can be better supported to – in the words of one person – “say who you are”, and gathered their comments together into key statements.

Then we asked each person if they agreed with each key statement. It is our belief our study (to be published later this year) is the first in the world to include only people with intellectual disability and to co-design all stages of research.

Where all too often people with intellectual disability are seen as the ones in need of education, our approach was the reverse. We asked for their advice to share with those who need to listen: policymakers, service providers, families and their supporters.

Read more: Film review: Thomas Banks’ Quest for Love tackles life as a gay man with disability

‘What matters is hope, freedom and saying who you are’

This Pride month is about celebrating diversity. But we have some way still to go.

The stigma around intellectual disability and LGBTQ+ identities means people may choose not to come out to the people or support services that surround them.

And when people do come out they are not always acknowledged or believed. As one study participant told us:

They say [an intellectual disability means] you can’t know you’re a lesbian but I’m in my body and I know who I am and I know I like girls.

Everyone we spoke to agreed it was essential to respect their gender and sexuality as LGBTQ+ people with intellectual disability.

Read more: In our own voices: 5 Australian books about living with disability

‘We want respect’

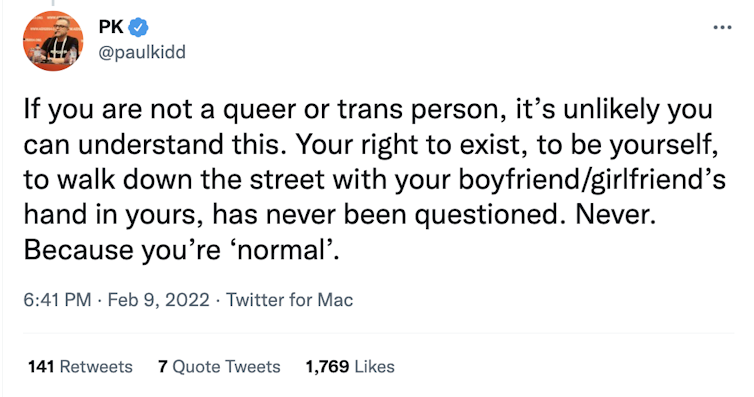

People talked about things that resonated with us as queer academics and reflected wider experiences of LGBTQ+ people.

This included negative mental health impacts following an increase in harassment and abuse during the postal survey on marriage equality and continuing anti-trans commentary and coverage.

Abuse extended into people’s homes, where paid support workers had verbally abused them with homophobic slurs. One person in this situation told us:

[…] there was a long time where I didn’t feel like I was safe [at home].

‘We want good people around us who understand us’

After a long wait following the initial community consultations, the National Disability Insurance Authority (NDIA – the body that runs the NDIS) released its LGBTIQA+ Strategy in 2020. The people we spoke to agreed there is a need to improve organisational culture and attitudes across the NDIA, partners and providers.

People told us support workers needed more training to understand their rights and LGBTQ+ identity, and provide support in line with the quality standards required for NDIS service providers. These affirm that “the culture, diversity, values and beliefs of that participant are identified and sensitively responded to”.

Read more: Creating and being seen: new projects focus on the rights of artists with disabilities

‘I want to be part of the queer mob – be who I am, on Country’

Research has previously reported the only place Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability do not experience inequality is within their own communities.

The Indigenous LGBTQ+ people with intellectual disability we spoke to told us how their spiritual connection and relationship to Country was an essential part of who they are. One participant, who identifies as a First Nations trans lesbian, shared her experience:

They call me sister and everything else, they don’t care if you’re trans gay or lesbian, it doesn’t matter what.

People talked about their need to access information, which helped shape our work in co-designing web-based resources for LGBTQ+ people with disabilities about donating blood, interactions with the police, their rights and more.

Lastly, we asked people what they would like to see in the future. One response was particularly poignant:

[…] being gay and free and no racism, be able to live peaceful.

The authors acknowledge our project partners Rainbow Rights & Advocacy and Inclusion Melbourne, and the members of our Advisory Group. We particularly thank our colleague and chief investigator Cameron Bloomfield.

Amie O'Shea receives funding from the National Disability Research Partnership and the Department of Social Services (Information, Linkages and Capacity Building program)

Diana Piantedosi is an Associate Research Fellow at Deakin University. Diana receives a Research Training Scholarship as a PhD Candidate at La Trobe University and is affiliated with Women with Disabilities Victoria (WDV).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.