Before the superhero movie, before the professional wrestling match, there was the circus.

The traveling circuses of the 1800s rolled around America showing off people with unusual talents (or, at least, the ability to fake such talents), and so-called strongmen were often the biggest draw. Crowds would gather to watch burly, now-forgotten icons like William Bankier, Eugen Sandow, and Arthur Saxon attempt to lift seemingly unliftable objects — massive barbells, tree trunks, pallets of bricks — while wearing flashy, often skin-tight costumes. The carnival barker would hype up each act of might as though the strongman were more than human. And, when you saw him lift his quarry above his head like it was made of tissue paper, you might even believe he was something supernatural.

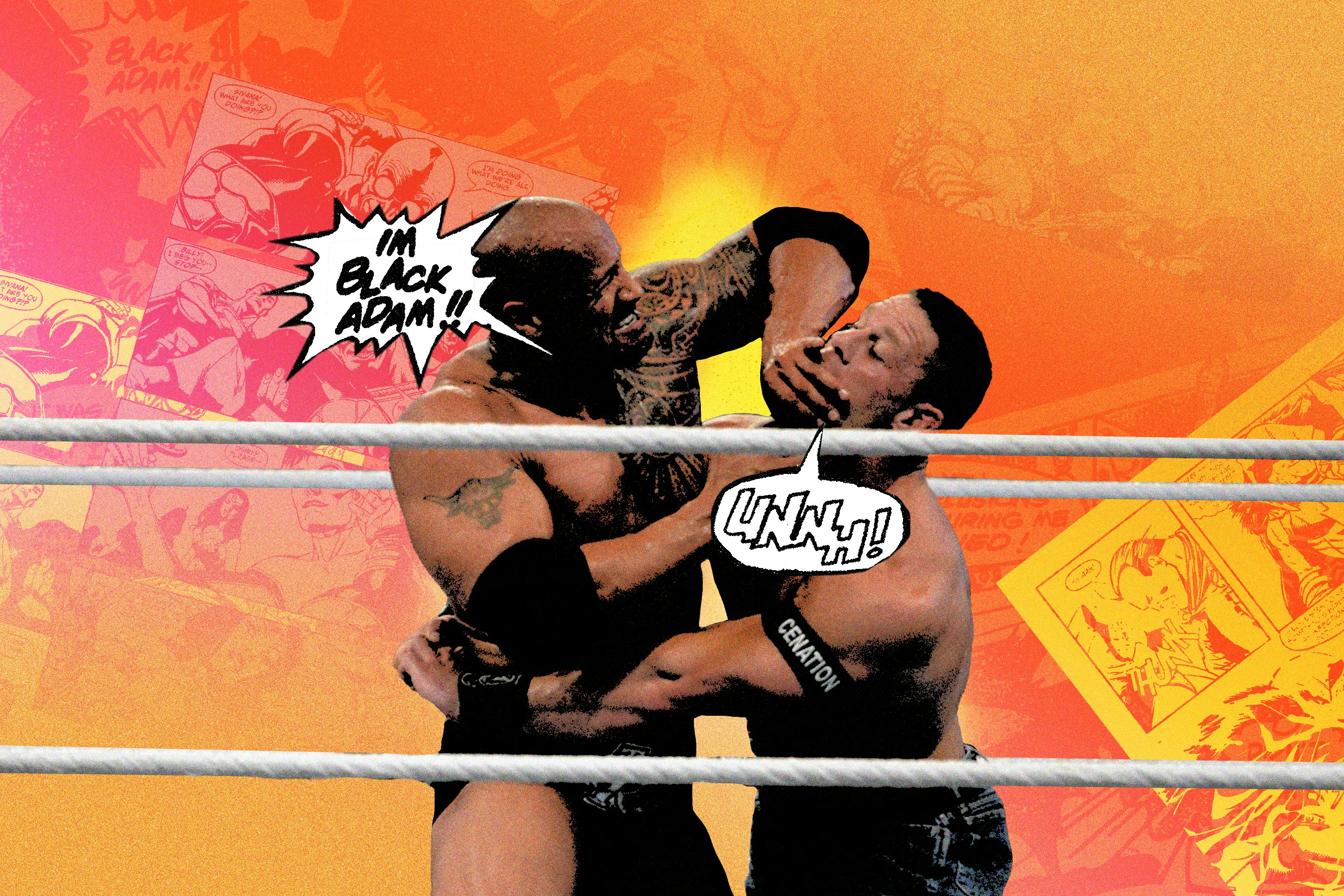

The inventors of Superman, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, partly based the visuals of that ur-superhero on circus strongmen. Pro wrestling began as a circus act featuring strongmen, then evolved into a billion-dollar industry. The superhero and wrestling ecosystems had divergent evolutions for more than a century but have recently started to converge again, most obviously by sharing talent.

This weekend, Dwayne Johnson, the blockbuster action star once known in the wrestling ring as The Rock, will realize the passion project he’s been trying to bring to life for more than a decade: the Warner Bros. superhero flick Black Adam. Johnson is an executive producer of the film, and he plays the title character, a (somewhat) honorable supervillain from DC Comics lore. He’ll go up against a ragtag band of do-gooders, but odds are decent that he’ll see the light by the film’s end and become yet another superhero (or at least a super-antihero).

Meanwhile, in another universe, Dave Bautista, who once dominated the ring as the wrestling character Batista, is set to reprise his role as Drax the Destroyer in Marvel’s next Guardians of the Galaxy picture. John Cena has been playing the lead in HBO Max’s dark comedy Peacemaker, based on a Charlton Comics superhero that DC bought. Wrestler Cody Rhodes had a guest role on the CW’s superhero show Arrow. And the door swings both ways: Arrow star Stephen Amell briefly made a go of it as a wrestler in World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE, formerly WWF) in 2015.

Given that both wrestling and superhero fiction glorify the male body in its most outlandishly muscular form — and that wrestling is a form of physical storytelling that requires tremendous strength and inter-performer trust — it only makes sense that casting directors would aim to put wrestlers in new kinds of spandex for the camera. And with the film industry consolidating around beloved characters, as opposed to box-office draw actors or directors, the work of superhero acting has more in common with the work of professional wrestling. It requires knowing how to keep your head down and do what you’re told in the service of whichever myth you’re employed by on a given day.

The making of superheroes has always involved the subordination of creative talent. The comic-book industry, which produces nearly all the source material for the superhero movies, has never had a union for writers or artists. All of its creatives are freelance, and the median annual freelance earnings for a comic-book writer these days is less than $70,000. If you’re working for the so-called Big Two superhero publishers, Marvel or DC, your work is almost always going to be “work for hire,” meaning you don’t own the characters or stories you create. Great creators die penniless with regularity. The ethos that keeps bringing in geeks to work cheap for superhero comics is this: You love this genre so much that you’re lucky to even be here.

There’s never been a wrestling union, either. All wrestlers are independent contractors and, unlike screen actors or professional athletes, risk their bodies while having to buy their own health insurance on the marketplace. Performance fees are unforgivably low, especially given the dangers inherent in the art form: The average working wrestler earns around $50,000 a year. WWE tightly controls what its freelance wrestlers say on social media and bans them from making money through outside partnerships. What’s more, you have to maintain what is known in the industry as kayfabe.

A notoriously difficult word to define, kayfabe (it rhymes with “Hey, babe”) is the set of executive-mandated lies that wrestlers must repeat, at the risk of being fired. Kayfabe used to mean pretending at all costs that wrestling was a legitimate sport; these days, it means pretending you’re happy with the poor working conditions and advancing various manufactured story lines about backstage drama. You do what you’re told. Your reality becomes what the owner, the promoter, wants it to be. And the nondisclosure agreements you’re forced to sign can be vicious.

All of which is to say that the superhero industry is a natural environment for wrestlers to thrive in.

Since the rise of the Disney-owned Marvel Cinematic Universe — with its reliance on surprise, tight control over spoilers, and firm hold on company narratives — superhero actors have been wrapped up in their employers’ kayfabe. Actors sign multi-picture or multi-season deals, with virtually everything shot piecemeal on green screen, and endure marathon global promotional obligations. It’s exhausting work with little creative gratification. (Gwyneth Paltrow, a recurring Marvel character, once implied she doesn’t always know what movies she’s in when she films them.) But these movies and shows live and die on the illusion that all the performers are having a great time and are honored to be involved. Wrestlers can deliver anecdote-packed interviews about their flicks with total kayfabe commitment. Henry Cavill’s an actor with a jawline; the Rock is an always-on promotion machine who never breaks character.

Superhero acting, like wrestling, requires knowing how to keep your head down and do what you’re told in the service of whichever myth you’re employed by on a given day.

Despite the downsides of superhero movies and TV, there are a lot of enticements for a wrestler. For one thing, the paydays are a lot bigger, of course. There’s also the prospect of SAG-AFTRA union membership and its attendant labor protections and health care. When wrestler (and eventual Minnesota Gov.) Jesse “The Body” Ventura tried to unionize the WWF locker room in 1986, someone snitched on him and the effort failed, so he left to perform in enough movies that he could get his union card and risk his life a little less. Most of his wrestling colleagues weren’t so lucky.

The prospect of escaping to Hollywood has enticed wrestlers to take even the most execrable of roles. Kevin Nash beat up the title character in 2004’s The Punisher but made little impression in the film industry. Though Paul Levesque, also known as Triple H, is a legend in the ring, few sing the praises of his role as a vampire in Blade: Trinity. And do you remember The Adventures of Superboy? No? Well, few do. But wrestler Lex Luger played an evil version of Superman in it in 1990.

In their massive success, Dwayne Johnson, Dave Bautista, and John Cena are very much the exceptions to the rule. Most wrestlers never make it to superhero roles, much less stable and lucrative ones. But when the lucky few do make it, they find themselves in a familiar situation: They’re subservient to an all-powerful corporate brand that supersedes the needs of the individuals who hold it up.

In wrestling and superheroes, the brand always comes first. However, there is some small bit of hope in Black Adam. As one of the film’s producers, Johnson has been far more involved in the creation and shaping of the project than actors typically are for a big-budget superhero picture. Plus, with nearly all the major superhero characters accounted for on film, Warner Bros. and Disney have to dig deeper and deeper into their catalogs of intellectual property for adaptation purposes. Characters like Black Adam are not world-famous enough to overshadow the actors playing them, let alone a performer with Johnson’s electrifying charisma and cross-genre appeal. This could be a harbinger of a future in which the balance of power between studios and performers tilts in actors’ favor.

But don’t hold out too much hope. We live in a world that wrestling and superhero fiction have colonized. Like the circus, they can provide fantastic entertainment. But, like the circus, if you really want to have a good time, don’t ask too many questions about what happens behind the curtain.

The Inverse SUPERHERO ISSUE challenges the most dominant idea in our culture today.