What Is the Great Resignation (AKA the Big Quit)?

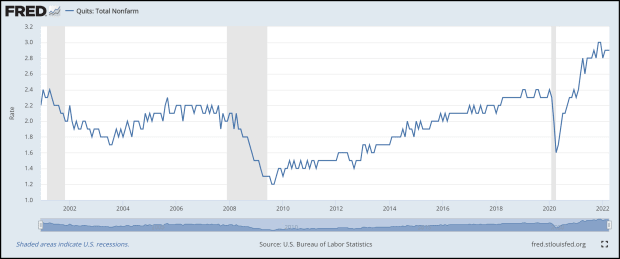

The Great Resignation—also commonly called the Big Quit or the Great Reshuffle—is an ongoing phenomenon involving employees voluntarily leaving their jobs in unprecedented numbers. According to most, this phenomenon officially began around late 2020 or early 2021, after the quit rate (the number of monthly resignations divided by total employment) dropped sharply during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic due to a shortage of work as a result of large-scale shutdowns.

Once vaccines were rolled out and restrictions were loosened, many companies resumed business, and the number of job openings increased. At the same time, the quit rate nearly doubled from around 1.6% in early 2020 to about 3% by late 2021.

According to most pundits, this uptrend marked the start of the Big Quit, but the quit rate, which started being measured in 2000, tells a different story. A graph of the data shows a slow but steady uptrend since 2009 that is only interrupted by the work shortage caused by 2020’s shutdowns and resulting layoffs. When looked at from this perspective, the great resignation is a 10+ year-old phenomenon that has been gaining momentum for years.

Bureau of Labor and Statistics via St. Louis FRED

What Conditions Led to 2021’s Great Resignation?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, so-called “essential workers” (e.g., those who worked at grocery and retail stores, hospitals, and restaurants) found themselves under-compensated and overworked by their employers, many of whom didn’t seem eager to reward the significant risks they were taking with anything more than shallow praise for keeping essential services available to the public.

Essential workers were commonly lauded as heroes, but few received the hazard pay one would expect to accompany such work. Because of this, many frontline workers felt like expendable cogs in an uncaring machine, and as more jobs became available in late 2020 and early 2021, workers left the retail, restaurant, grocery, and hospitality industries in record numbers.

During the COVID-19 shutdowns, many companies whose businesses weren’t based around manufacturing or customer service shifted toward remote work for office-type employees, and the office-based workforce realized that this could become the norm. Why spend money and time commuting to an office when the same work could be done at home? In many cases, remote work also meant that money could be saved on child and pet care.

As vaccines became widely available and shutdowns subsided in late 2020 and early 2021, an abundance of job openings meant workers had more options, and due to the high cost of living and the lifestyle changes brought about by the pandemic, many weren’t satisfied with jobs that didn’t offer living wages or flexible work environments.

Money from unemployment and federal stimulus payments also meant that some workers had enough cash on hand to search more thoroughly for positions that met their requirements rather than accepting less-than-ideal work in order to survive after quitting.

These and other factors contributed to low unemployment and high labor demand, which made for an environment that favors workers’ ability to resign and seek new prospects.

What Reasons Did Workers Give for Quitting Their Jobs?

According to surveys created by the Pew Research Center, “low pay (63%), no opportunities for advancement (63%), and feeling disrespected at work (57%)” were the top three reasons respondents cited for leaving their jobs during this particular wave of resignations. The study also showed that younger adults and those with lower incomes quit at higher rates than older adults and those with higher incomes.

What Did People Do After Resigning?

So, where did all these people go after resigning from their jobs? The answer is unsurprising—they got other jobs. According to the Bureau of Labor and Statistics, the quit rate and swap rate had a correlation of close to 100 percent. Workers weren’t resigning just to resign; they were resigning in order to leverage their labor and land themselves jobs with better pay, better benefits, and more flexibility.

With unemployment low and labor demand high, companies had to compete with one another for job seekers by providing incentives. According to the New York Times, “When workers switched jobs, they often increased their pay. Wages grew nearly 10 percent in leisure and hospitality [from May 2021 to May 2022] and more than 7 percent in retail,” two of the industries most heavily hit by the Big Quit.

In some cases, non-resigning workers were also able to leverage this shift in the labor market by demanding better pay and more flexible conditions. For many office workers, this often meant the ability to start (or keep) working remotely.

Do Workers Have More Bargaining Power Than They Did Before 2020?

In general, the conditions that existed during the Great Reshuffle shifted a degree of bargaining power from employers to workers. But will it stay that way? In general, the more demand there is for labor, and the lower the unemployment rate, the more bargaining power workers (and job seekers) have.

Interestingly, this shifting power dynamic seemed to bring about a resurgence in the labor movement, as a wave of unionization efforts followed the Great Resignation. These efforts were not, in most cases, welcomed by large employers, many of whom—such as Amazon and Starbucks—invested considerable capital into union-busting efforts and other (sometimes illegal) forms of retaliation. Nevertheless, unionization efforts continued. By May of 2022, 100 Starbucks stores had voted in favor of unionization.

Concurrently, many workers expressed their mutual solidarity in online communities. A subreddit called r/antiwork grew by over 900,000 members in 2021 and drew the ire of Fox News, a network that tends to be associated with right-wing, anti-labor-movement politics. Within the r/antiwork community, workers not only shared stories about low pay, horrible working conditions, and villainous bosses—they also shared legal information about workers’ rights and the unionization process.

Members encouraged each other to be transparent with their coworkers about pay and reminded one another that the prohibition of discussions of pay in the workplace by bosses and managers is against the law. The community continues to grow, and as of mid-2022, it had over 2 million members.

Is the Great Resignation Still Occurring?

The quit rate has fallen somewhat from its November 2021 peak, but as of late June 2022, it remains relatively high at about 2.9%. Unionization efforts are still on the rise, and workers are learning about their rights and collective power.

Given the Great Resignation’s generally upward trajectory since 2009 and the resurgence of the labor movement, it doesn’t appear as if the Big Quit is going anywhere anytime soon. According to Katherine Ross’ interview with ZipRecruiter CEO Ian Siegel, the “post-pandemic job-seeker” is here to stay.