What Is a Real Interest Rate?

A real interest rate is the difference between a nominal interest rate and the rate of inflation.

Nominal interest rates are the rates set by financial institutions, such as banks and credit card companies, to be paid as interest on borrowed money. These are also the rates at which money can be earned from a savings account, bond, or certificate of deposit.

Money earned or paid on interest can be deceiving, however, because the rate of inflation isn’t taken into account. A high inflation rate can erode purchasing power, and at the same time, reduce the value of payments on debt in real terms, which is why the real interest rate provides a better picture of either.

Real Interest Rate Examples

For example, putting $1,000 into a savings account that earns 2 percent annual interest at the start of the year would yield $1,020 by year’s end. But with an annual inflation rate—based on the consumer price index—of 10 percent, there’d be no interest earned, and the "real" value of savings would erode by 8 percent, meaning that the deposit (in real terms) would be valued at an inflation-adjusted $920 by the end of the year.

If, however, the savings rate was 10 percent and the inflation rate was 2 percent, the real interest rate would be 8 percent, which means that the savings account would be valued at an inflation-adjusted $1,080 by year’s end.

The same goes for interest rates on debt. A borrower would benefit from a higher inflation rate if the rate of interest were lower. Yet, the bank issuing the debt would be on the losing side because it would earn no interest in real terms.

That would be especially so if rates are fixed. However, if lending terms aren’t fixed, then banks can alter interest rates, such as with adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs), to account for changes in the inflation rate.

How to Calculate Real Interest Rate

The simplest way to calculate the real interest rate is by subtracting the inflation rate from the nominal interest rate.

How Does Monetary Policy Affect Real Interest Rates?

The Federal Reserve can influence the direction of the economy with its monetary policy. High inflation may push the central bank to tighten monetary policy, while low inflation could spur looser policy.

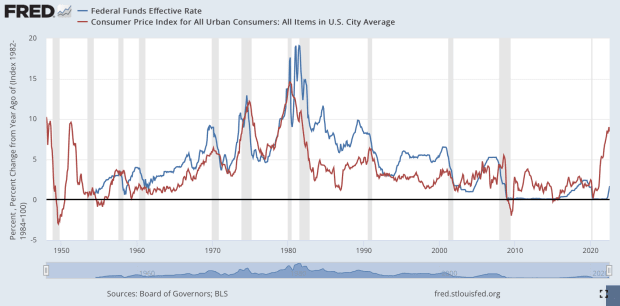

Below is a graph comparing the federal funds effective rate (which is the weighted average rate that borrowing institutions pay to lending institutions) to the consumer price index from July 1954 to July 2022. The effective rate, represented by the blue line, has usually been above the rate of inflation, in red. Real interest rates were positive most of the time, except in certain periods, such as in the mid-1970s and early 2000s.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007–2008, the Fed followed a zero-interest-rate policy from December 2008 to December 2015 to spur economic growth. Inflation tended to stay below 2 percent during that time, and the target range for the federal funds rate was pegged between 0 and 0.25 percent.

The Fed slowly started to raise interest rates to keep up with inflation beginning in 2016. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, though, rates were lowered to close to zero to help aid in economic recovery. But as inflation started to creep up in 2021, the Fed has lagged in its response with rate increases.

The graph shows that the Fed’s aggressive monetary policy (in the form of sharp rate increases) tends to precede recessions, which are highlighted by shaded areas of gray.

Can the Real Interest Rate Be Negative?

If the inflation rate exceeds the nominal interest rate, then the real interest rate becomes negative. Negative real interest rates are bad for savers because (in terms of purchasing power) they do not actually earn interest from their deposits when adjusted for inflation. It is also bad for banks because inflation reduces the real return of a loan.