RenoBeranger frompixabay; Canva

What Is a Liquidity Trap?

A liquidity trap happens when an economy is in a recession but interest rates are already the lowest they can go, 0%, which is also known as the “zero lower bound.” What else can a central bank do to spur growth? That is the conundrum.

People think the main job of a central bank like the Federal Reserve is to manage interest rates, and in so many ways they are right: Low interest rates spur economic growth and add more money into consumer’s pockets so they, in turn, can buy more things. High interest rates make it tougher for banks to loan to businesses and consumers (and other banks), but they help curb dangerous inflationary pressures that could cause the everyday items we use to be too expensive.

But what happens when interest rates are as low as they can go but the economy remains at a standstill? The Fed must get creative to come up with ways to escape the liquidity trap, or else it can lead to—or prolong—deflation.

What Happens in a Liquidity Trap?

While central banks may hold the reins to monetary policy, what happens to the stock market during a liquidity trap? In a nutshell, too many investors wait on the sidelines and don’t invest their money, not even in typically low-risk securities like Treasuries. Likewise, people hoard their cash as savings and don’t spend it. What gives?

You could say that, when interest rates are zero, the opportunity cost of holding cash is also zero, because there is less incentive to invest your assets into 1-year bonds, for instance, since your yield will be minimal (although it should also be noted that bond prices move inversely to the fed funds rate). The Fed maintains that “movements in its policy rate are associated with similar movements in short-term interest rates.”

In addition, people could also be hoarding cash because they are afraid of an impending crisis or economic shock, such as war or a large-scale health event like COVID-19. Alternatively, they could be worried about their earnings potential shrinking (i.e., losing their job) during a negative event, like a recession or deflation. During a liquidity trap, people want their assets to be liquid, which means easily convertible to cash.

Usually, a decrease in interest rates spurs growth, but when rates are already at zero, the central bank is nearly out of options—and it takes a lot to persuade people to change their spending habits.

Examples of Liquidity Traps

While liquidity traps may sound alarming, they have occurred more frequently than investors might think.

The Great Depression

Economist John Maynard Keynes described the phenomenon of the liquidity trap as early as 1936. In the General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Keynes discussed reasons why the American economy could not lift itself out of the Great Depression. He believed the problem was a fundamental lack of demand for goods and services, which resulted in a lack of demand for labor.

Only when spending increased—particularly by the government—would demand grow, production increase, and thus, more workers get hired. Many argue that America’s entrance into World War II finally ended the Great Depression because the government started spending up a storm to create weapons and artillery to ensure success for its soldiers. Keynes’ views had a profound impact on the field of economics, and many still subscribe to his theories today.

Japan’s Lost Decade

In the 1990s, Japan was facing a particularly deep economic crisis. An asset bubble had formed in both its housing and stock markets, and its central bank had implemented a series of steep interest rate hikes to quell it—to disastrous consequences.

Overleveraged banks and insurance companies, which were loaded with bad debts, needed to be bailed out by the government. Businesses teetered on failure, and many replaced their full-time employees with temporary workers, offering no benefits. Japan’s economy stalled, and prices declined. Interest rates were cut, but its citizens sat on their savings instead of spending them. The country experienced crippling deflation, and it would take over a decade for it to recover.

The COVID-19 Recession

Some analysts believe that after the COVID-19 stock market crash and subsequent COVID-19 recession, the U.S. economy entered a liquidity trap—even though the Federal Reserve had quickly instituted quantitative easing measures as well as helicopter money.

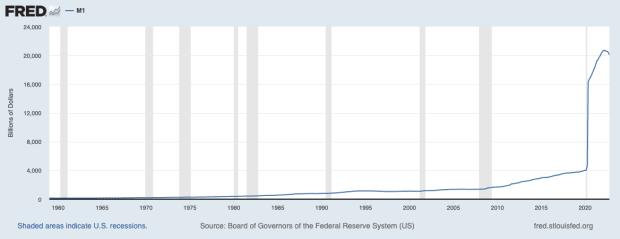

People hoarded cash. The graph below, from FRED, the Federal Reserve’s data center, depicts just how much cash on-hand, known as the M1 money supply (made up of currency and liquid deposits, such as savings), had skyrocketed during this period. It was astounding.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), M1 [M1SL], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M1SL, October 25, 2021

How Can Liquidity Traps Be Avoided?

If central banks run “out of ammo” with interest rates, as Keynes put it, they could turn to expansionary fiscal policies to dig out their economy from the liquidity trap.

What does that mean? Simply put: increasing the monetary supply.This could happen in a number of ways:

Quantitative Easing

Large-scale asset purchases, are also known as quantitative easing. Through this program, a central bank buys trillions of dollars of long-term securities—mainly government bonds. This increases market liquidity and fosters a favorable lending environment for banks, who in turn make it easier for their customers to take out mortgages and business loans.

In the wake of the Great Recession, the Fed’s balance sheet grew by $3.5 trillion between January 2009 and December 2013. And while critics believed that the practice of QE can prolong liquidity traps because it keeps long term interest rates low, in an April 2014 article published by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, economists Maria Arias and Yi Wen reiterate that inflation did not result from this endeavor. They point to increased communication from the Fed with its public—who reinforced their stance that QE would eventually be reversed—as one of the main reasons why.

Helicopter Money

Helicopter money is another unconventional method of jumpstarting an economic engine. This involves injecting large sums of money into the economy through increased government spending such as entering a war, providing tax cuts, or offering a direct cash stimulus. After all, if you suddenly received a no-strings attached check from the U.S. government, would you add it to your savings account, or would you spend it?

Economists believe that helicopter money works best in deflationary environments, since it tends to ignite inflation and can also weaken the dollar.

Raising Interest Rates

And if nothing else is working, this may seem counterintuitive, but raising interest rates actually could help. After all, so much of what happens in the markets boils down to a matter of supply and demand. As interest rates rise, other financial assets simply start to look more attractive to investors than holding cash, so demand for cash decreases.