If you've ever hit the gym with Russian twists, squats, lunges, or lateral lunges during workouts — you’ve already used the planes of motion. In fact, you use them during your daily activities without even realizing it. But what are they exactly? Below, we cover what planes of motion mean and why they matter during exercise.

Planes of motion refer to multidirectional movement, including forward and backward, side-to-side and rotation. Pulling, pushing, twisting, jumping, lunging — all of these movements occur across the planes of motion. Simply walking around during the day or turning to change direction uses them too, but there are many reasons you should use them during workouts.

The best way to build a robust, mobile and agile body is to use all three. Read on to find out more about the planes of motion, the benefits and why they matter.

What are the 3 planes of motion?

The three planes of motion are:

- Frontal: sideways movement

- Sagittal: forward and backward

- Transverse: rotational or twisting movement.

360-degree movement is crucial for stability, balance and muscular coordination. If you only move in one direction, your range of motion will be pretty poor, and various muscle groups will become underused, which places undue pressure on overused joints and muscles. After a while, this can cause overcompensation, pain and injury.

3D movement will make you a stronger, faster and more agile athlete in the gym and improve your functional movement during daily activities, like carrying groceries or climbing the stairs.

Here’s a breakdown of the three planes of motion.

Sagittal plane movements

The easiest way to remember the sagittal plane is to imagine sliding a sheet of metal down the middle of your body, from your head to your toes, separating the body into left and right halves. You can only slide along that sheet using forward and backward motion.

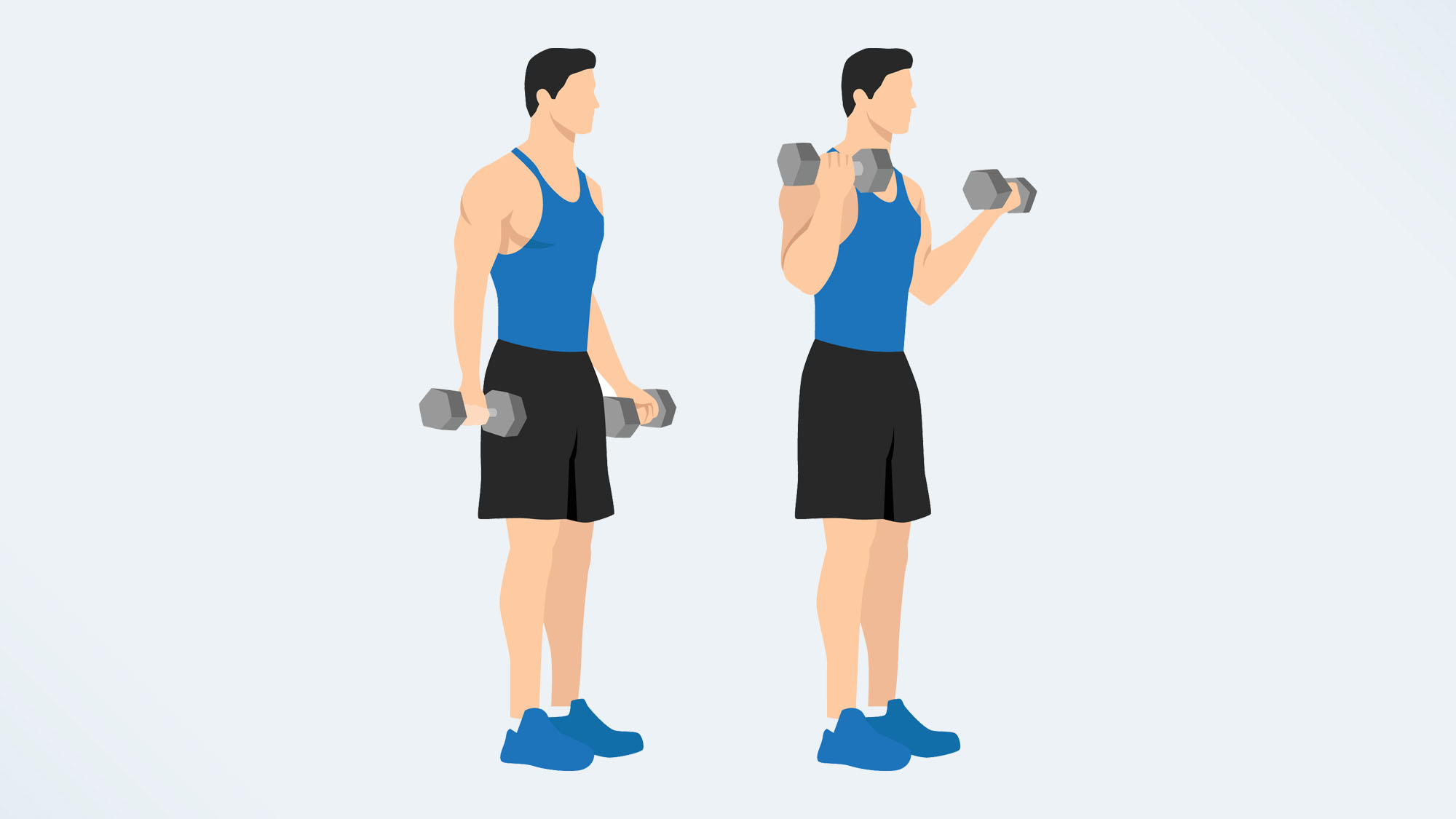

Flexion and extension exercises like biceps curls and triceps extensions are sagittal plane motions, as the arm bends and extends at the elbow and moves forward and back. So are exercises like front lunges and frontal raises.

Trickier ones to figure out include the squat, but it comes back to what your joints are doing — flexion and extension at the hips, knees and ankles. Without sideways or twisting motions present, the “standard” vertical squat sits in the sagittal plane. Dorsiflexion (lifting the toes, feet, or hands backward) and plantar flexion (planting the toes, feet, or hands down) also count as sagittal movement.

Frontal plane movements

The frontal plane cuts the body straight down the middle into the front and back body, meaning you can only move from left to right (side-to-side) along this imaginary metal sheet.

Exercises like lateral lunges or lateral raises all exist along the frontal plane (the name confuses things, right?), and require abduction and adduction at the hips and shoulders. Other examples include raising your leg to the side or running or walking sideways.

It’s important to remember the joints can still flex and extend (bend and straighten), but the primary portion of the movement comprises sideways motion.

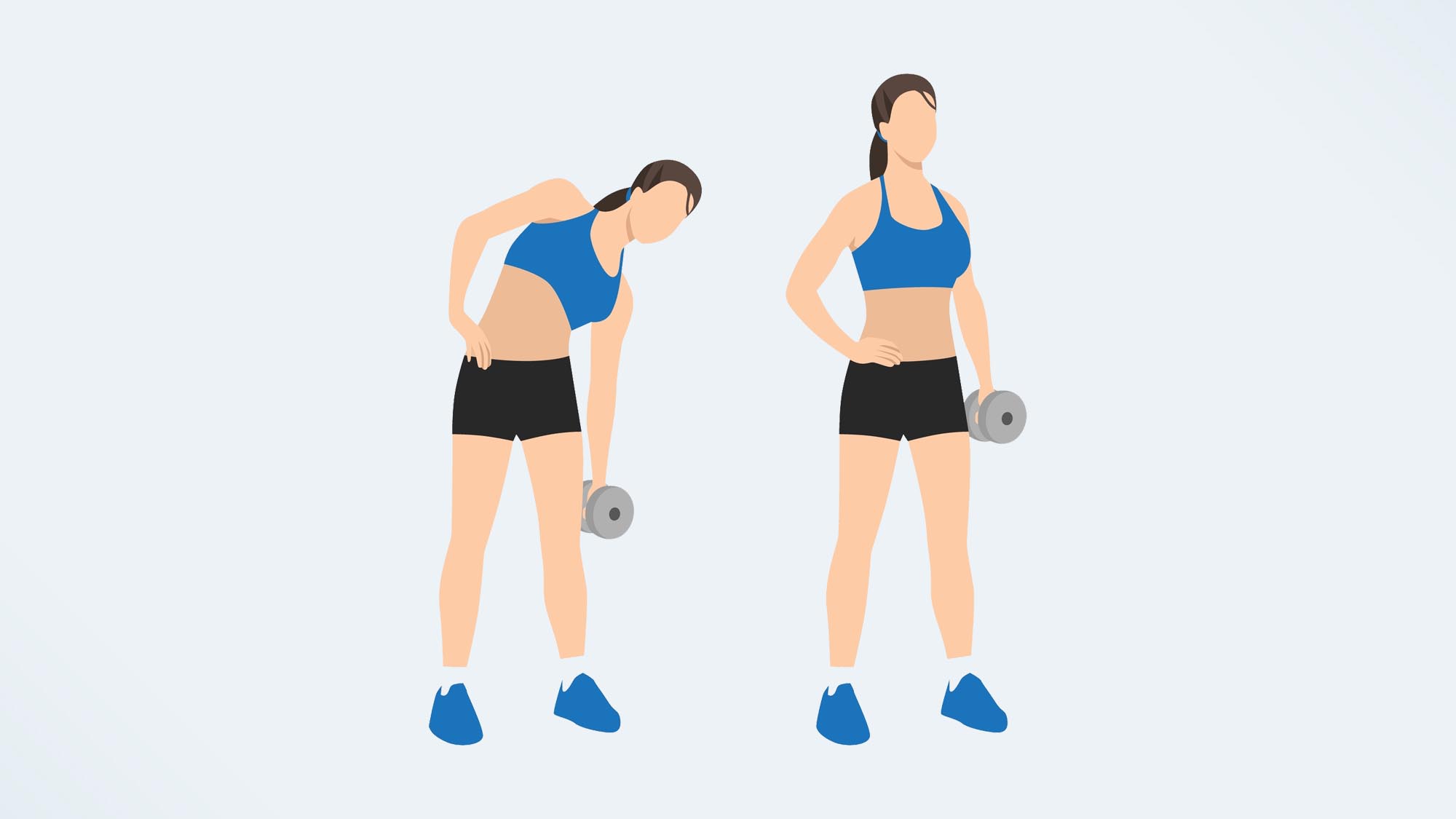

Other exercises in the frontal plane include side bends when you laterally flex the body — think about sliding your hand down the side of your leg — to work your oblique muscles, along with inversion and eversion movements like rolling your ankle or foot inward and outward.

Transverse plane movements

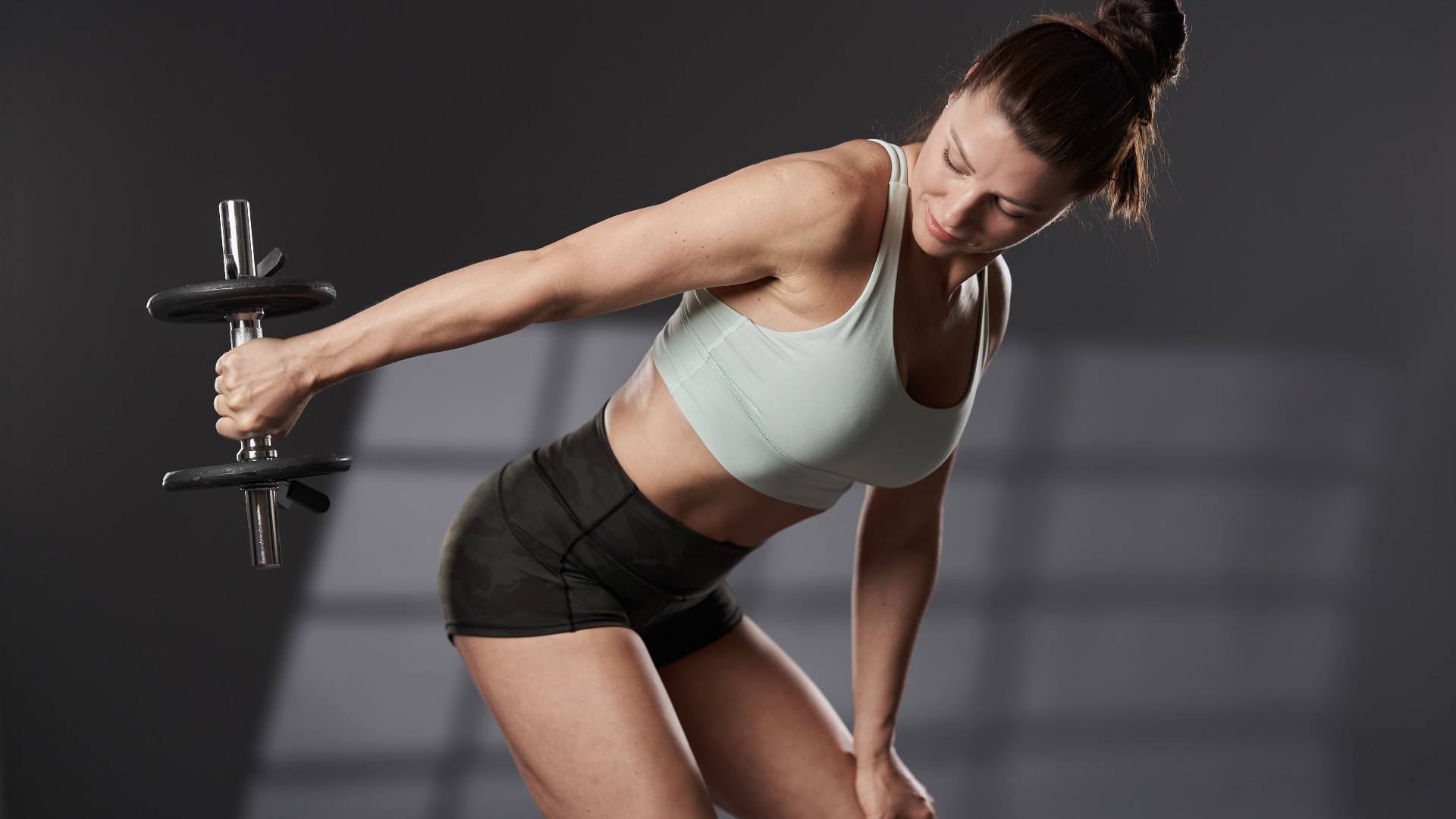

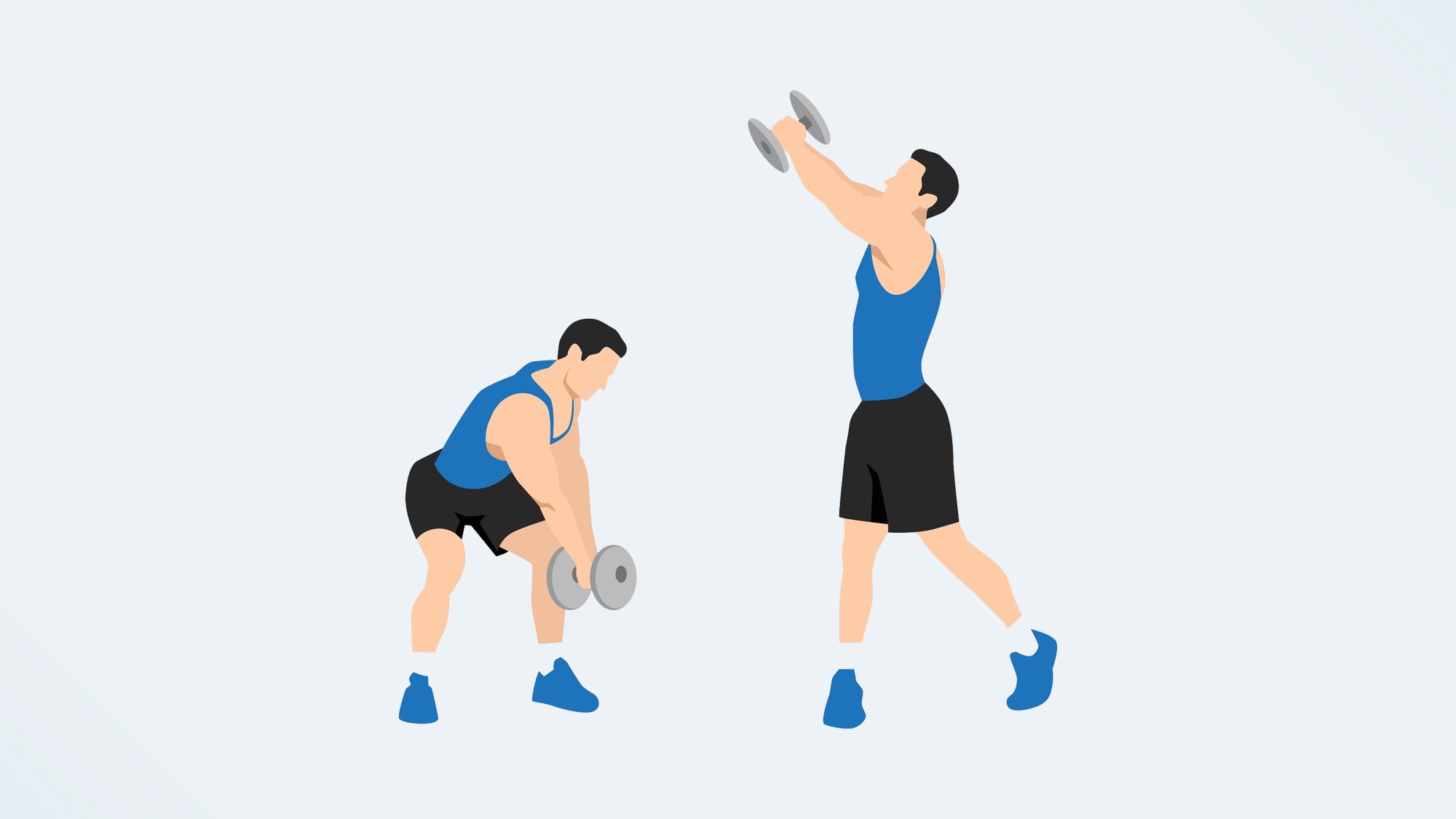

The transverse plane cuts the body into top and bottom, slicing through the middle of the body, and includes any movement like twisting or rotation. Russian twists or woodchops are easy examples, but the transverse plane also includes limb rotation, including internal (toward the body) and external (away from the body) rotation of your arms, shoulders, hips, legs, ankles, or feet.

It’s a more “free” motion, so swinging the arms or legs around can also sit in the transverse plane, and so does any movement that requires your arms or legs to move inward or outward (toward or away from the body) using a 90-degree position.

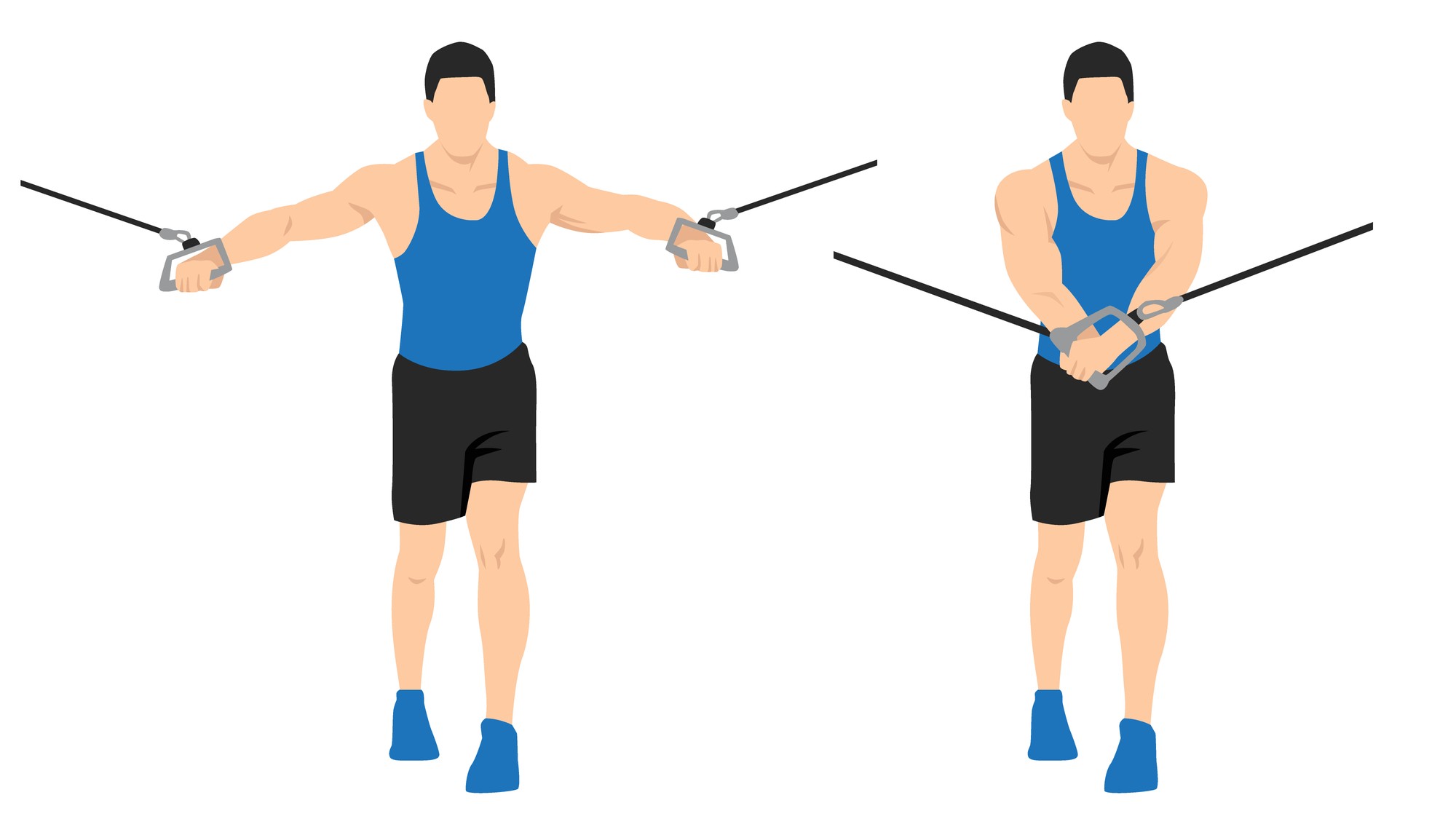

That’s when things can get confusing, but the best way to think about it is by using the chest fly and seated hip abduction as examples. Think about the movement pattern of a chest fly, as the arms draw an arc forward and backward with a bend in the elbows — it doesn’t sit neatly into the frontal or sagittal plane, and it’s technically a transverse motion because the shoulders rotate. The same goes for the seated hip abduction, where the knees are bent, and the legs are 90 degrees as the hips rotate to abduct the legs from a seated position.

Bottom line

Whether you’re programming exercise for yourself or someone else, to guarantee 360-degree muscular activation, simply add exercises from all three planes of motion during upper and lower-body workouts or core programs.

Working in all directions of motion is hands down the best way to strengthen the most muscle groups and joints (and more evenly), create balance, core stability and coordination and improve the mind-muscle connection, teaching muscle groups to recruit and work together.

The best functional training programs will use the planes of motion, getting exercisers to twist, run and lift weights in every direction, controlling weights through various ranges of motion and learning to resist motion in different planes, too.

The same goes for exercise programs amongst elite athletes and sportspeople who use various agility drills, balance training and plyometric exercises in their training regimes. As a coach, incorporating these principles into your client’s programs will help prevent injury and strengthen weaker areas.