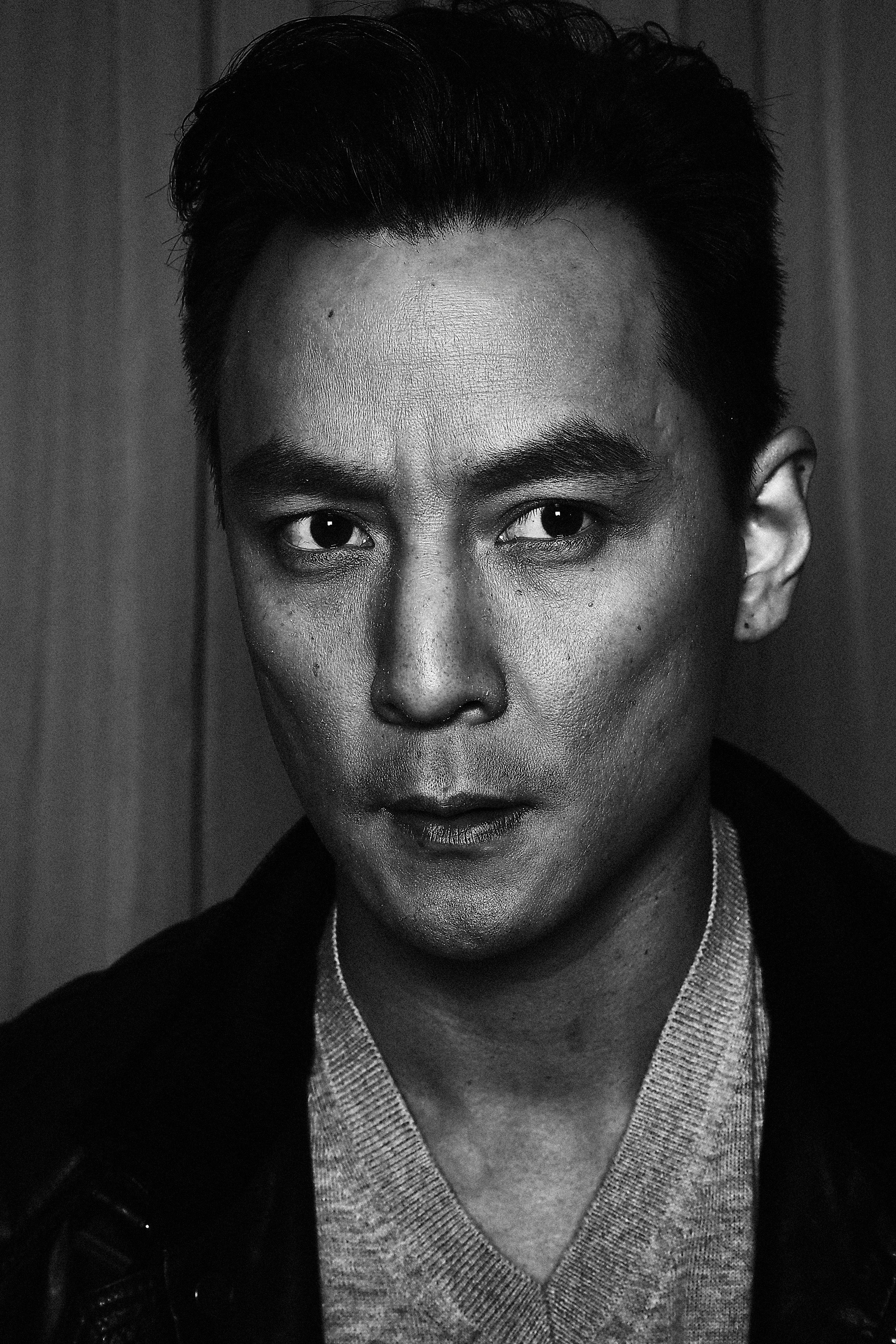

Daniel Wu never wanted to play the Monkey King. Then, he almost died.

In his career in Asia spanning over two decades, Wu had several chances to play Sun Wukong, aka the Monkey King, usually in more straightforward adaptations of the 16th-century Chinese novel, Journey to the West. But he never felt it necessary.

“I just didn’t think there was anything new I could bring to the table,” he tells Inverse.

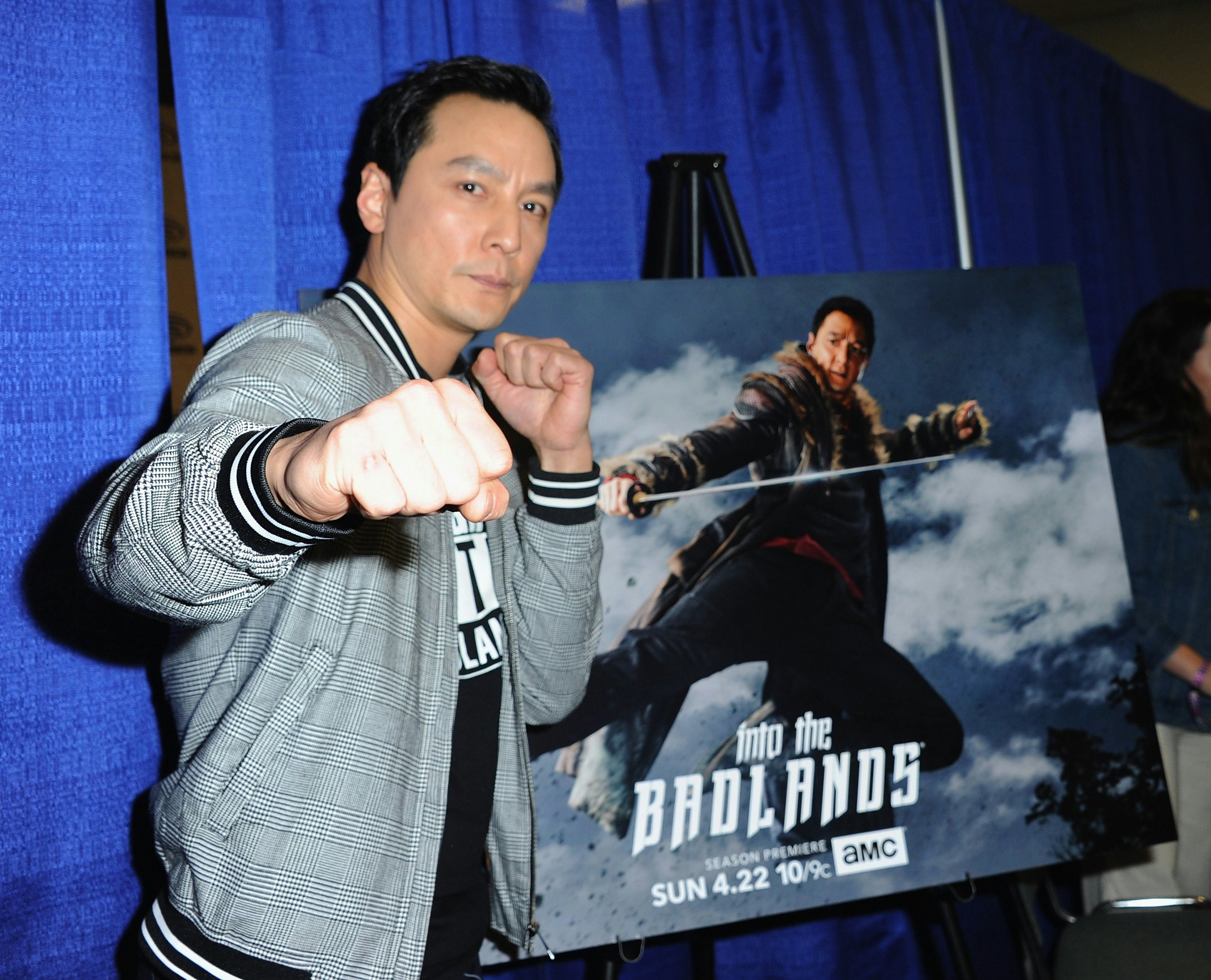

But in American Born Chinese, the new Disney+ action-comedy based on the award-winning graphic novel by Gene Luen Yang, Wu takes on the role of the immortal hero Sun Wukong. The legendary figure is perhaps one of the most prolific characters in Eastern culture, with film titans including Stephen Chow and Donnie Yen playing the part in movies, and anime like Dragon Ball loosely adapting the classic epic. But, ironically, Wu may be one of the few people to play the character twice — technically. Into the Badlands, AMC’s post-apocalyptic series loosely based on Journey to the West, saw him playing “Sunny,” a chopper-riding, sword-wielding assassin inspired by the Monkey King.

In the years since Badlands put the longtime Hong Kong star on the map for American audiences, Wu has been on his own epic journey westward. He co-starred in 2018’s Tomb Raider and had a recurring part in HBO’s Westworld. But after Badlands ended in 2019, Wu had a health scare that nearly brought his career to a halt.

“I thought it was food poisoning,” Daniel Wu says. It was a burst appendix, and Wu’s doctors told him he narrowly escaped death.

The brush with mortality caused him to reevaluate his life and career choices, coming to the conclusion that he needed to pursue the career choices that he wanted. “It made me realize I needed to reinforce the relationships I valued in life,” Wu says. “I needed to really go for the things I want in life, and pursue those to the fullest. Honor the time I have with the opportunities given to me.”

In a way, Wu reached a moment of enlightenment not unlike the kind that Sun Wukong achieves when he embarks on his perilous journey to India in the classic story. Which is why it might have seemed like serendipity when the offer for American Born Chinese came in — and with it, another chance to have a go at a character that had given his career new life in America. “It really is a special opportunity,” Wu says.

“Americans think I’m just a kung fu star, and that’s not really indicative of my whole career.”

In American Born Chinese, Wu stars as Sun Wukong, that mythical figure from Chinese literature who mentors a Chinese-American teenager simply trying to fit in at his high school. Such a story resonated with Wu personally. Despite a prolific career in Asia, he’s felt the pangs of alienation on either side of the Pacific.

“Working in Asia, I was welcomed, but I did feel like an outsider,” he says. “Working on projects like Westworld, I was the only Asian American on set. So you would feel isolated in that way. This project was really special in that a lot of people working behind the scenes and in front of the camera were Asian American, and it felt like a real family environment in that we all came from shared experiences that we touch upon.”

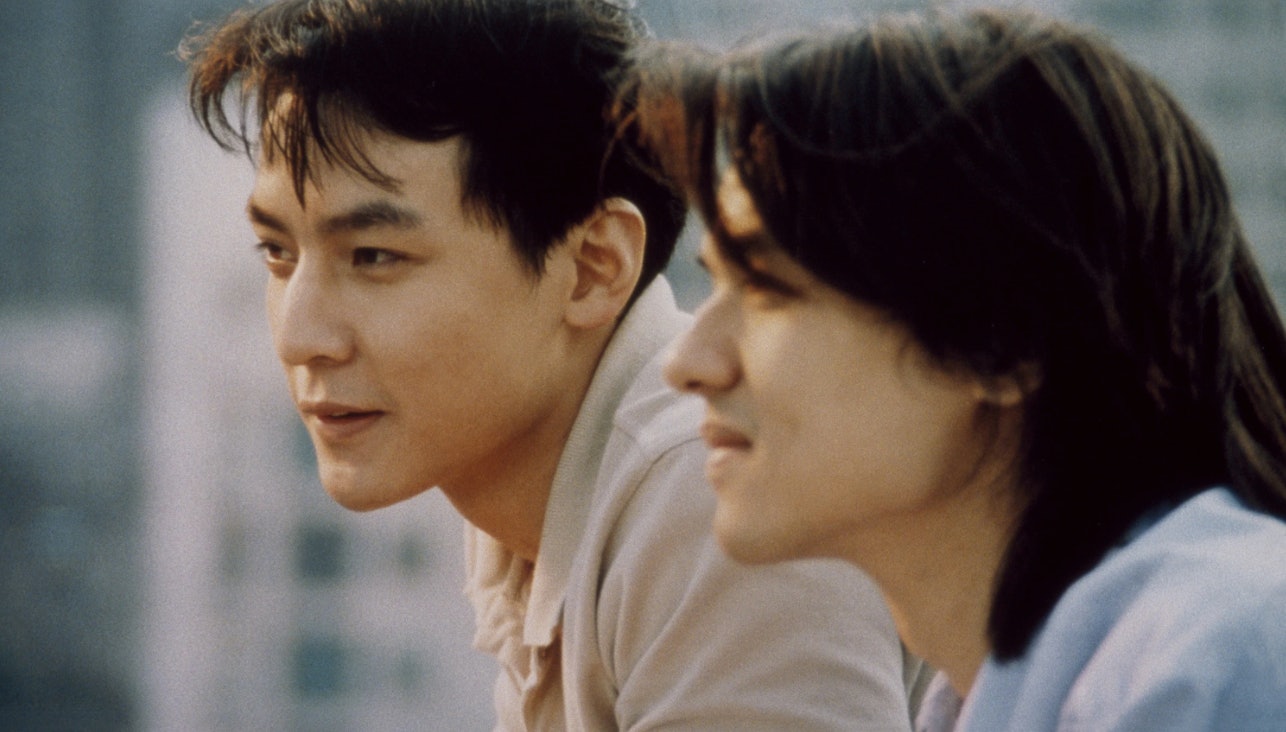

Born in Berkeley, California, to Chinese parents, Daniel Wu grew up idolizing the titans of Hong Kong cinema like Jet Li, Donnie Yen, and Jackie Chan (the latter he’d later work with in blockbusters like New Police Story and Shinjuku Incident). Wu’s heroes inspired him to take up wushu at age 11, but he had no ambitions to be a movie star. In 1997, Wu began a modeling career in Hong Kong. A clothing ad brought him to the attention of the director Yonfan, who launched the careers of Maggie Cheung and Chow Yun-fat, who cast Wu in his 1998 drama Bishonen.

Thus began a long career in both the Chinese and Hong Kong entertainment industries, including a stint as the lead of boy band Alive. Only a handful of his Asian films feature martial arts. The majority are comedies, thrillers, and romantic dramas. These diverse flavors of the human experience are what Wu aspires for in Hollywood, even while the industry has obnoxiously framed him as another kung fu import. Daniel Wu, in fact, is homegrown.

“Americans think I’m just a kung fu star, and that’s not really indicative of my whole career,” he says. He estimates of the 80-plus projects he’s done in Asia, “only two or three are martial arts focused.”

He adds, “I’m seen as a character actor here, or an action star, as opposed to my career in Asia. I would like to do a romantic comedy, or a drama, things I was doing in Asia. It’s about undoing that stereotype of seeing an Asian male face and thinking, ‘He knows martial arts.’”

Wu’s determination to undo stereotypes is in part channeled by his post-recovery vigor to simply accomplish all he imagines for himself. He’s in a strange and all-too-rare position of getting to say “no” to opportunities if it doesn’t suit his ambitions.

“After Into the Badlands, a lot of the offers I was getting were martial arts roles,” he says, “I knew if I’d taken those, I’d just be cornered as a martial arts actor. I purposely turned them down. I’m at a point where I don’t rely on every job to pay the bills. I have the luxury to pick and choose what I want.”

Ironically, he has Jackie Chan to thank for teaching him.

“He told me one time, ‘You can do much more than action,’” Wu recalls, revealing Chan’s own desires for more than what the American film industry believed he could do. He remembers the legend telling him: “I would love to do drama, I would love to do roles like De Niro, but nobody sees me as that. No one will invest in films like that for me. So try as hard as you can to stay out of one genre and be as broad as possible.”

“That advice I took,” Wu says, along with his own firsthand observations of the pain Jackie Chan endured at his age. “I witnessed what it’s like to have chronic pain from all the injuries Jackie’s had. I realized I don’t want to be in my 60s in constant pain. It’s not worth that.”

Not that Wu isn’t proud of his action work. He still harbors fond feelings for Into the Badlands, its cult status, and the sheer diversity of talent across its production. “I tremendously miss it,” he says. “I would have liked to complete the story. But it did a lot for me in terms of building my confidence as a producer, and taught me a lot about leadership and how to run a production.”

He hints the show’s unseen fourth season would have resembled the story of American Born Chinese, however abstract. “It was going to be about my son’s character growing up, and Sunny being the guide,” Wu reveals. “A more in-depth, father-son relationship. And the father was gonna be a spiritual guide for the son's growth.”

Though he misses playing the badass Sunny, this older, wiser Daniel Wu finds more in common with the fatherly Sun Wukong of American Born Chinese, which departs from more traditional portrayals of a rebellious and rambunctious Monkey King who still needs to grow up.

“Being a parent allowed me to understand this character more,” he says, “Especially since COVID and I had to do distance learning with my daughter. I realized I’d become a ‘Tiger dad.’ I caught myself saying things my dad used to say and I swore I never would to my own kid. I started realizing the wisdom of parents, but you also can’t be a helicopter parent all the time.”

He adds, with the wisdom of an enlightened parent, “I want my daughter to forge her path. I'm not trying to mold her into a better version of me, which maybe I originally was trying. I realized that to be her best self, she needs to find that on her own.”

In 2020 during widespread racist rhetoric and violence against the Asian community over COVID-19, Daniel Wu used whatever fame he had to promote community activism, and offered up financial rewards for information on assailants of elderly Asians. Now with a show like American Born Chinese, Wu hopes that stories can continue to do some good.

“It’s important for boys and girls, like my daughter, to see our stories on screen and be proud of that,” Wu says. “To see Chinese mythology on Disney+, introduce our culture to a broader audience, we can be proud of. I keep saying I’d like to see this year for Halloween kids wearing Monkey King outfits. We get a stage to spread our culture in a beautiful way.”