People who don’t fit the dominant demographic of where they live can often be asked, “Where are you really from?”

In 2017, CNN surveyed about 2,000 people who shared their stories on social media with the hashtag #whereiamreallyfrom. The participants included first- and second-generation immigrants, naturalized individuals and others who were native-born citizens.

As a classical studies scholar with a focus on linguistic and cultural diversity in Imperial Greek and Latin literature, I am aware that this question is not a new one.

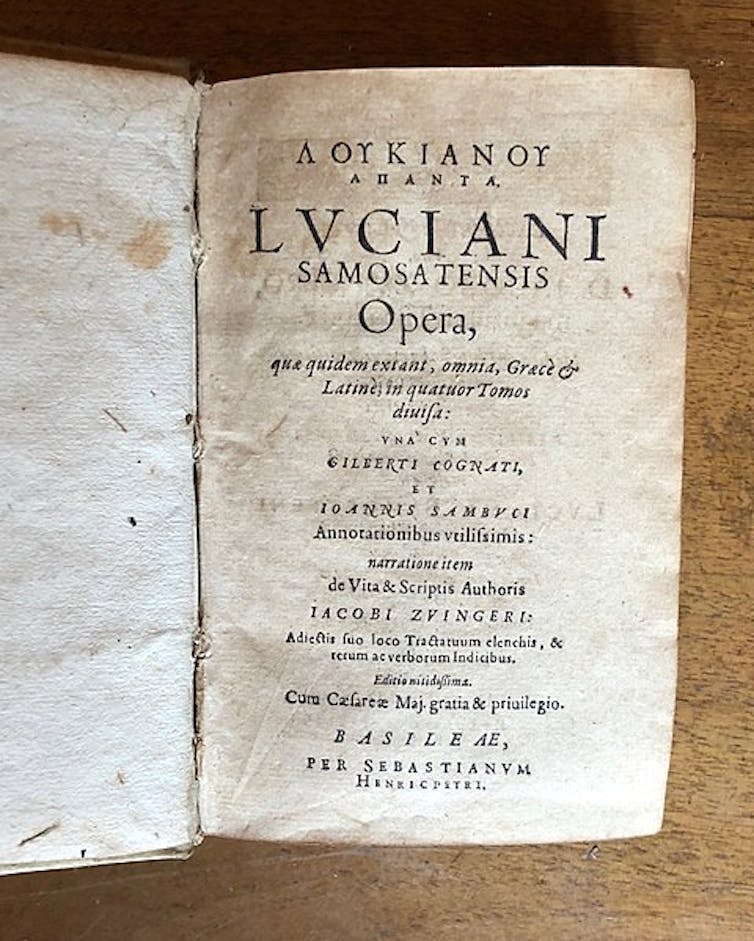

Take Lucian, a high-ranking Roman official in the second century. Born in Syria, he later chose to be a naturalized Roman. As a non-native speaker of Greek and Latin who, by his own admission, looked different from many people in Greece and Rome, he dealt with issues of ethnicity, language use and social acceptance.

The Roman world

The time of the Roman Empire is a unique historical period that, in many respects, can be seen as a lived lesson for issues of diversity and inclusion. By Lucian’s time, the Romans had conquered Spain, France, parts of Germany and Britain, Greece, the North Africa coast and much of the Middle East, among other territories.

As occupiers, they did impose their rule with military means. Still, they accepted their subjects’ differences, granted privileges to several provinces and gave citizenship on a case-by-case basis until A.D. 212, when everyone was given Roman citizenship.

Their pragmatic aim was to maintain stability and ensure cooperation. The result was a multilingual, multicultural and cosmopolitan empire. People were allowed to retain their ethnicity, language, culture and religion for the most part. Latin was [not imposed except in the army] and administration; Greek was established as the language of the educated.

This period could be said to resemble our current times: People traveled, relocated and worked in different parts of the empire. Also, there were scholars and writers who were trilingual and multicultural. For instance, there were African authors who wrote in Latin and were also fluent in Greek, and Romans who were fluent in Greek, too.

These authors wrote about their sense of identity and belonging and were proud of their ability to remain true to their origins while also adapting to the conditions of the global world of the empire. On the other hand, there were also other authors who were anti-immigration and critical of new citizens and non-native speakers, and others who showed that Roman occupation weighed heavily on their subjects.

So, where was Lucian really from?

Lucian is a cosmopolitan individual. He was born in Samosata, which was in Syria until it was incorporated into the Roman Empire. He traveled to Cappadocia, Pontus, Athens, Rome, Gaul and Egypt. He wrote in perfect Greek; he was in the entourage of the Roman Emperor Lucius Verus and served as the secretariat of the Roman prefect in Egypt.

Throughout all his works, Lucian clearly suggests that he should be accepted in this new world as the model of the new citizens – individuals who were open about their ethnic identity yet embraced the Greco-Roman culture and contributed to advancing contemporary social inclusion.

In his essay “The Dream,” Lucian imagines his future as an underrepresented citizen. He writes that two women appeared in his sleep: an elegant one representing Greek education and a rugged one representing a craftsman’s life. The former promised him a life of popularity among the world’s elite. He chooses to be a well-to-do man of letters who overcame his humble origins and succeeded in a cosmopolitan society, even though he was not a native speaker or a native citizen.

In another one of his writings, “Zeuxis,” he writes about about his fluency in Greek and insists that he should not be seen as an outsider because he is as articulate as any native-born Greek speaker.

He becomes more emboldened in his treatise “A Slip of the Tongue in Greeting.” Here, he intentionally makes a mistake in a salutation and supposedly writes to apologize. In reality, however, he shows his knowledge of Greek cultural norms and, at the same time, clearly proves that he is versed in Roman culture, too.

On the other hand, he also wrote a piece titled “My Native Land,” in which he says that no matter the languages one learns, the cultures one acculturates oneself to, and the global recognition, they are always their motherland’s sons and daughters – proud of them and indebted to them.

Lucian’s work provides a unique insight into a world of imperialism that also fostered multilingualism and multiculturalism and gave birth to the first global citizens. His writings show what diversity and inclusion can look like through the eyes of the empire’s newest citizens – and offers illuminating lessons from an often forgotten classical past.

Eleni Bozia does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.