In 1853, a Roman vase was found being used as a container for ashes in a grave outside Roman Colchester. Dating to the later second century AD, it depicted four gladiators with their names scratched into the surface of the vase.

Two of the gladiators, Memnon and Valentinus, were shown as the classic pairing of a lightly armed but nimble retiarius (net man) and heavily armed but cumbersome secutor (pursuer). The retiatius, Valentinus, has lost his weapon – a trident – and holds up his finger as a sign of submission.

Long thought to be an import, fabric analysis has now shown the vessel to be of local manufacture. The ashes the vessel contained were of a male of about 40 years of age and not of local origin. Could he have been a gladiator?

Gladiators are one of the emblematic images of the Roman world. Massive amphitheatres, depictions of gladiators in Roman art and literature and more recent portrayals such as Russell Crowe’s portrayal of the Roman general-turned-fighter, Maximus Decimus Meridius in the film Gladiator (2000) have all contributed to the perception of blood and gore, crowd frenzy, Christians and lions, the caprices of emperors.

The origins of gladiatorial spectacle go back to the Roman Republic (the ancient state centred on the city of Rome founded in 509BC), where it was originally associated with funeral games for prominent men. Gladiators represented a propitiatory blood offering, skirting close to being a form of human sacrifice.

By the second century BC, gladiators had become professionals, forming corporations under a lanista (trainer). Normally selected from prisoners of war, criminals and slaves, they had little if any social standing. Nevertheless, as the Colchester vase shows, they could become celebrities and could be awarded the rudis (a wooden sword signifying freedom).

Gladiatorial weapons training was introduced to the Roman army and thereafter there was a strong link between soldiers and gladiatorial games. Many amphitheatres in the European provinces were built at colonies of military veterans (coloniae), meaning they became part of the monumental equipment of Roman-style cities in the empire and beyond.

So the construction of amphitheatres and the staging of gladiatorial games in a province such as Britain shows the local populations buying into this aspect of Roman cultural values as sponsors and as spectators.

Most amphitheatres in Britain were not constructed in stone, but were instead large banks of earth carrying timber seating, a little like American “bleachers”, either side of an elliptical arena with entrances at either end. Large examples such as that at Cirencester could have sat several thousand people. They showed off the assimilation to Roman ways of the local nobles who financed their construction and the games.

Gladiatorial combat’s strong links with the army explains why the two major stone amphitheatres in Britain were at the legionary fortresses of Chester and Caerleon. Colchester was a colony for military veterans, so an amphitheatre there would be expected, though archaeologists have not yet located one.

Evidence of gladiators in Britain

More tangible evidence of the gladiators themselves in Britain is harder to come by. But some recent discoveries allow us to flesh out the picture.

There must have been an amphitheatre at the long-lived, legionary fortress of York, but it is yet to be discovered. Excavations between 2004 and 2005 at York’s Driffield Terrace uncovered 82 Roman burials and 14 cremations dating largely to the third century.

The sex and age profile of the buried bodies was very unusual. They were almost all males and aged from their late teens to their early forties.

These men were generally taller and more robust than the average male burial from Roman Britain. Evidence suggested that they had geographically more varied origins than men from Roman York in general.

Extraordinarily, more than half of the men had been decapitated, the skull placed in the grave with the corpse.

How to interpret them? Given that the age range is that for service in the Roman army, one hypothesis was that they were soldiers executed for serious offences. But further research has shown evidence that they suffered blunt force trauma, often to the head. Could they have been gladiators?

Intriguingly, the pelvis of one of the men has indentations consistent with the bite of a large carnivore. Perhaps an instance of the Roman capital punishment of damnatio ad bestias – being thrown to the beasts in the arena.

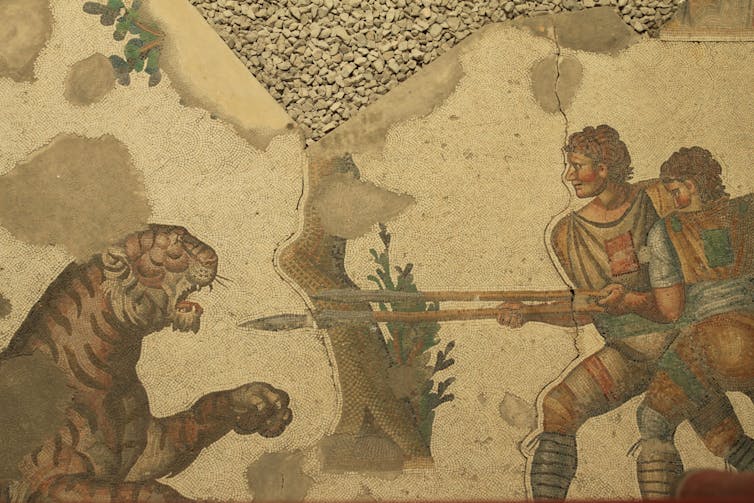

Occasionally, other finds suggest an interest in gladiatorial combat in Britain. Three mosaics from villas in Sussex, Kent and the Isle of Wight show gladiators, but since at one site this entailed cupids dressed as gladiators, these were probably just artistic conventions rather than representations of Roman British reality.

More convincingly, pieces of pottery with representations of gladiators have been recovered from both Chester and Cirencester – both places with amphitheatres. These were in red gloss pottery mass produced in present-day France. Perhaps they were imported as souvenirs for people attending gladiatorial spectacles.

Other objects show the hold of gladiators on the popular imagination, such as an ivory clasp knife handle showing a gladiator from the Roman fort at South Shields.

It seems that by the fourth century AD the amphitheatres in Roman Britain were falling into disuse as cultural tastes shifted. But as the Colchester vase has shown, people in Roman Britain – at least for a time – viewed gladiators as celebrities, not unlike modern day sports stars.

Simon Esmonde Cleary does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.