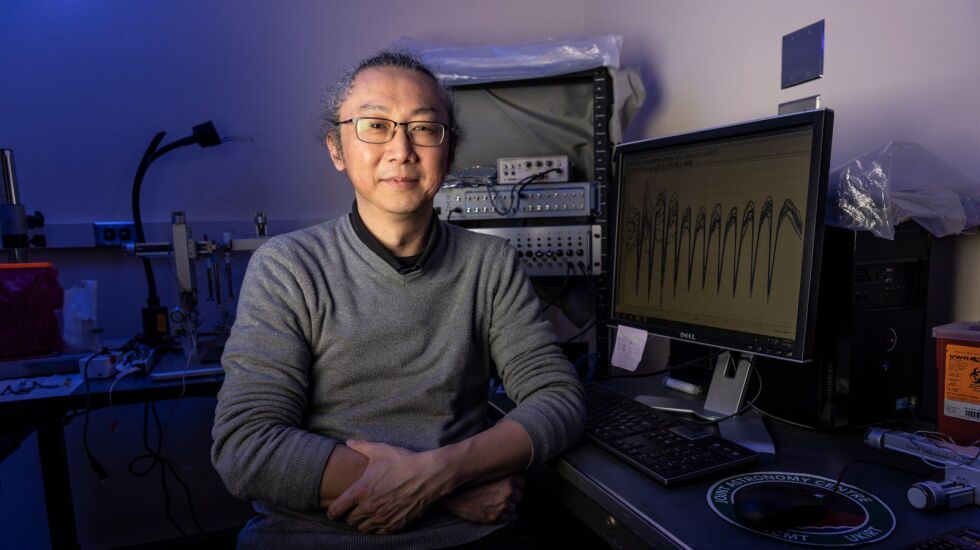

The experiment’s setup, or rig, as Kuei Tseng calls it, looks like a cartoon version of something cobbled together by a mad scientist.

Clear plastic hoses snake from jars and containers down to two large, liquid-filled beakers on the floor and back up and around, ending in a tiny pipette poised at an angle under a high-powered microscope. It’s called a patch clamp, and it sounds like a backyard water fountain as it gurgles in the lab on the sixth floor of a University of Illinois Chicago medical building on Wood Street.

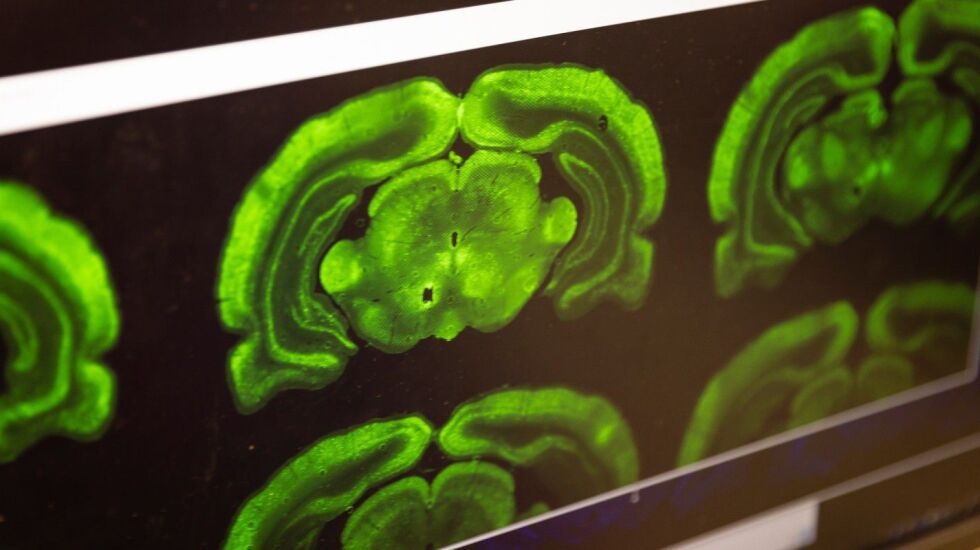

A lab assistant spins a dial, bringing into focus on a screen a rodent brain cell about one-seventh the diameter of a human hair. It’s from a teenage lab rat that was high on tetrahydrocannabinol — THC, the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana.

The cell will live for only about five hours in this solution. But its reaction to stimuli during the experiment offers Tseng, 50, who is one of the country’s foremost neuroscientists, and his research team clues regarding an important question:

How bad is smoking or ingesting weed for a teenager?

High on marijuana, Tseng’s lab rats, chosen at an age that equates to a human’s teenage years, are being studied to better understand long-term effects of cannabis on the teenage brain.

It’s no secret that getting high makes it harder for teenagers — and adults — to learn, remember, focus, use motor skills and do complicated things. And THC stays in the body for days, even weeks.

But what about long-term effects — for instance, will smoking weed regularly at 16 make my kid a bust at 30?

On that, Tseng’s research suggests that there’s much more that people need to know.

Modeling the adolescent brain

The rapid wave of marijuana legalization has moved faster than the research on its health effects. In 2020, Illinois became the 11th state to legalize marijuana for recreational use. The law requires buyers of recreational marijuana to be 21. But no one doubts that weed, in all its forms, is more freely available and perhaps more appealing to teenagers than ever. More teenagers think of it as a natural substance, not a harmful drug, surveys have found.

So far, no dramatic increase in young users has been seen, according to Dr. Wilson Compton, deputy director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, though one-fifth of high school seniors have used cannabis in the past 30 days, according to a recurring University of Michigan survey called “Monitoring the Future.”

What has changed is the scientific evidence about what marijuana can do to the developing brain. Teenagers who use marijuana regularly are more likely to quit high school or not get a college degree, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But what’s the biological evidence behind that?

Tseng’s rodent studies indicate that regular marijuana use prevents the teenage brain from fully maturing. Previous studies found IQ deficits in adults who used marijuana in their teens. But those results were hotly contested in the scientific community.

Tseng, who trained as a medical doctor in Argentina, has become a key figure in the emerging field of biological psychiatry. His research has uncovered big differences in the brains of adolescent and adult rodents.

Key to these differences is the brain’s internal cannabinoid system, a relatively recent discovery. Our brains are a virtual cannabis factory, producing their own supply that helps carry chemical messages to and from neurons. Cannabinoid receptors are in parts of the brain that influence pleasure, memory, thinking, concentration and movement and act like traffic signals to regulate almost every aspect of our functioning. They turn up the body’s heat and signal hunger.

They are also, Tseng’s research has found, a vital mechanism in engineering an adaptive, mature brain through adolescence into adulthood.

When people use a vape pen or eat a gummy infused with THC, they are ingesting a substance that looks about the same to the brain as its natural cannabinoids. The ingested THC molecules flood the brain’s receptors with a wave of excess chemical messages that hijack the brain’s normal processing.

In a teenager, though, the brain’s prefrontal cortex isn’t fully developed. That doesn’t happen until about 20 to 25 years old.

Toying with that circuitry while it is still malleable appears to have long-lasting effects on intelligence, social behavior and other capabilities, according to research by Tseng and other neuroscientists.

For one of Tseng’s studies, lab rats — about 30 to 50 days old, which, given their lifespan, equates to human teenage years — were injected with THC. Rodents that were high during adolescence showed impaired learning lasting long into adulthood.

In such experiments, typically a rat will hear a buzzer and receive a mild electrical pulse. When the rat hears the buzzer again, it freezes up, anticipating the pulse. After a few instances of a buzzer but no shock, the rat will learn and stop freezing up.

But when adult rats that were given THC as adolescents heard the buzzer, they continued to freeze up even in the absence of a shock.

Tseng’s conclusion? That the rats’ adolescent brains had been impaired by cannabis and did not develop to their full potential in adulthood, so they couldn’t process the new information.

“That brain maturation process stopped somewhere,” he says. “The normal gain of that maturation didn’t happen.”

Confronting human questions

One night a few years ago, Tseng was invited to speak about his research at a bar in Lincoln Park for an audience of parents and teenagers. Parents wanted to know whether it was healthy for their kids to smoke marijuana. The kids wanted to know how much was too much.

Tseng, who doesn’t have kids, told them he’d rather that teenagers not use cannabis. But he says, “I would never say, ‘Don’t do it.’ It’s your call, not my call.”

Tseng is hesitant to answer such questions because there’s still much more to learn.

Such as:

- How long is the period of susceptibility in adolescence?

- Why is cannabis delaying or stopping brain development?

- Can the effect be reversed?

Research investigating such questions is being carried on all over the world.

Hanna Molla, 34, co-authored a 2020 overview with Tseng of rodent and human adolescent brain performance on cannabis. Molla’s scholarly path began after she worked in a drug detox facility and grew curious about why various drugs had profound effects on people.

“There’s so much that’s not known about cannabis,” says Molla, who is now conducting studies on microdosing LSD in the lab of veteran drug researcher Harriet de Wit, founder of the Human Behavioral Pharmacology Lab at the University of Chicago.

Another graduate student who rotated through Tseng’s lab, Conor Murray, 33, is finishing an experiment that aims o determine whether Tseng’s rat results can be reproduced in humans. In a study at the UCLA Center for Cannabis and Cannabinoids, Murray is using mobile headbands to measure brain waves to see whether heavy, lifetime cannabis use shows up as a biomarker of brain development.

Tseng is building new rigs for what promises to be one of his most innovative studies. In the past, Tseng’s lab injected rodents with straight THC. Under a five-year, $2 million grant proposal, a group of lab rats would inhale cannabis piped into a specially made box called a “smoke jammer.” They’d get five puffs over 30 minutes and the next day the same thing for about five days in a row. He hopes to learn more from that about how and why cannabis alters the maturing process of the teenage prefrontal cortex.

More potent marijuana

While Tseng is studying rodent brains, other researchers are five years into the most comprehensive study ever done of brain development in young people. More than 11,000 children are being tracked from 9 years old to 20 at 21 study sites around the country for what’s called the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study, or ABCD, which is tracking drug and alcohol use, screen time and other formative influences.

Such a study has become possible only in the past 10 years because of technological improvements in data storage and brain imaging and leaps in understanding of the brain, says professor Krista Lisdahl, director of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Brain Imaging and Neuropsychology Laboratory.

The portion of the ABCD study that Lisdahl coordinates touches close to home. Her 14-year-old son is the same age as the study volunteers.

“Having a kid and being a parent, it just increases my motivation to provide some evidence-based parenting advice,” Lisdahl says.

Like Tseng, she says she isn’t anti-cannabis. But, in her view, age and potency are two big risk factors. Consider that the weed that previous generations could get was milder, with about 2% to 6% THC. Today, it’s 15% to 25% for plant products, known in the industry as flower. And some cannabis extract products — like edibles, oil, shatter and dab — have far higher levels of THC, from 50% to as much as 90%.

Vaping cannabis is especially risky, Lisdahl says, because the THC concentrations are higher, and the device is portable and easy to hide.

“The way I explain it to my own son: I don’t think it’s worth it in your teenage years,” Lisdahl says. “You’re laying the groundwork for your career, for your social groups, your physical and mental health. The effects are subtle. But, to me, if you’re trying to build your brain, you want to avoid risk factors like cannabis and alcohol. It does not optimize your cognitive development.”