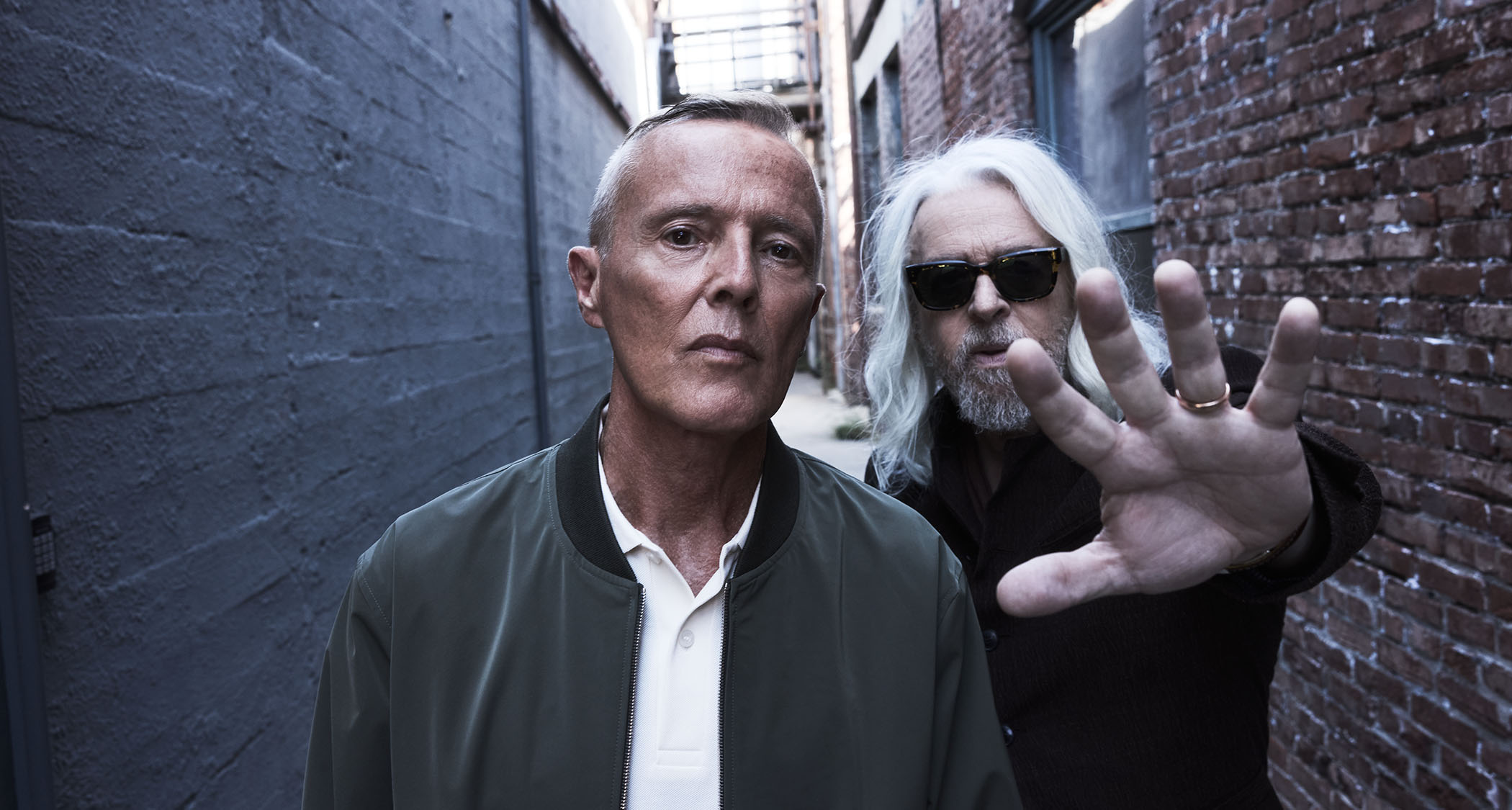

Curt Smith and Roland Orzabal have known each other long enough that they can finish each other’s sentences but what they can’t do is predict with complete certainty how their song ideas might land with one another, and maybe this is what keeps Tears For Fears so hard to second guess after all these years.

The not knowing is a fundamental element in their creative chemistry. What each of them is looking for is surprise. “Totally, 100 per cent. I sometimes work on things and I’m not sure myself, to be honest with you,” says Orzabal. “They’re not fully formed. They’re not fully finished, and I’m close to them, obviously. We had a writing session, Curt and I, I took No Small Thing back to England, and I wasn’t sure about it at all.”

Ultimately it was Orzabal’s wife, Emily, who convinced him to send No Small Thing over to Smith. Her intervention was crucial, because the song was the key that unlocked the sound and emotional register of their 2022 studio album, The Tipping Point.

“I’m always attracted to the stuff that slightly different and less obvious, the songs that are slightly out of the ordinary,” says Smith, bathed in sunlight, while Orzabal, checking in from the UK where it’s almost midnight, sits in a darkened room – it is as close a Zoom call gets to music video production values.

Released nigh-on 18 years after their post-reunion comeback, Everybody Loves A Happy Ending, The Tipping Point was a heavy lift. Smith says No Small Thing was the epiphany they were looking for, all because it wasn’t what anyone would have expected of them.

“I really felt that that was gonna be the thing that kind of the glue that brought this album together,” he says. “You need those songs on every album. That brought the album together in a weird way. On Songs From The Big Chair, I think The Working Hour is that song. They don’t necessarily have to be the hits. It’s something that just has that depth that makes the whole album work.”

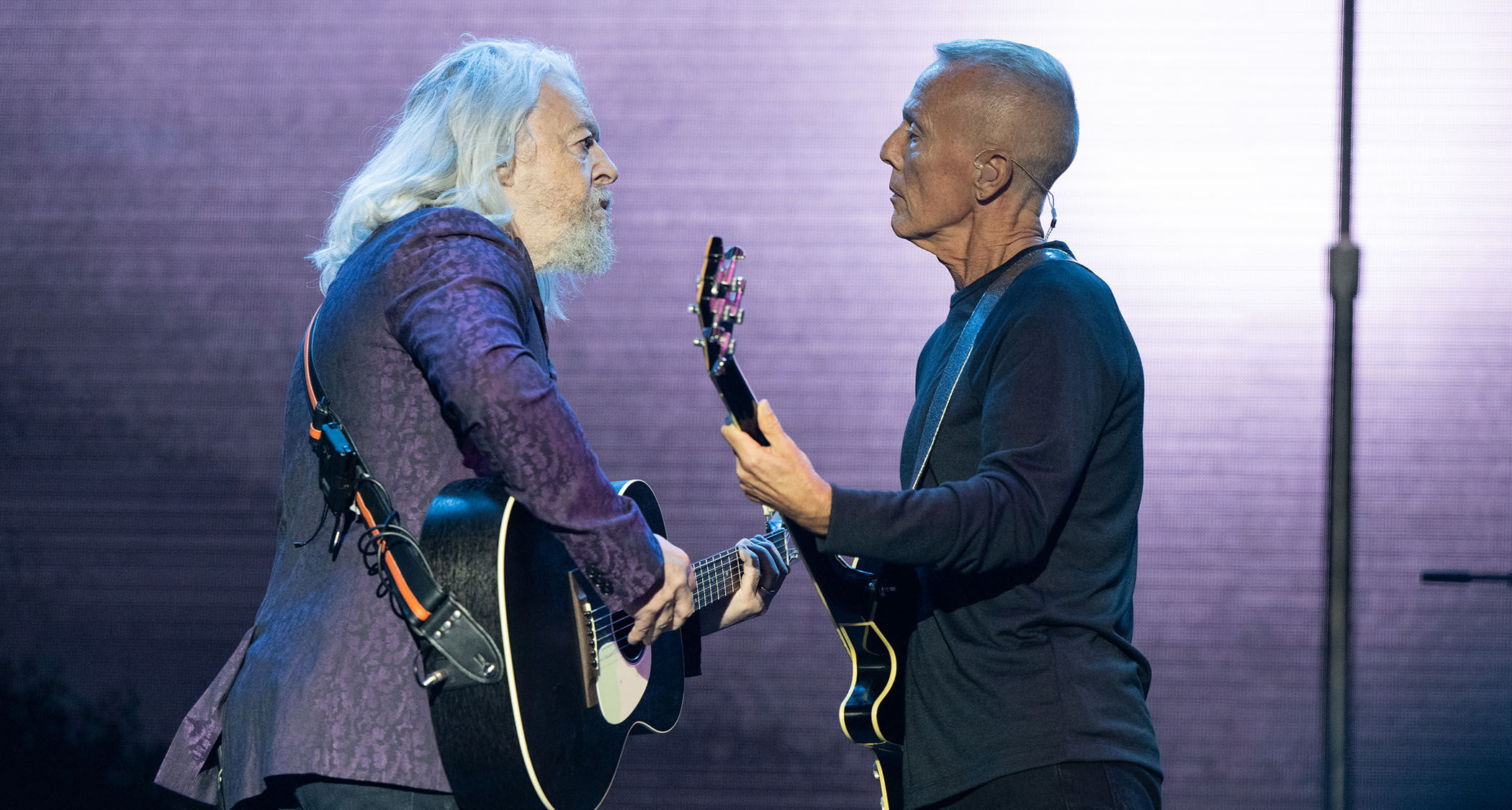

No Small Thing was constructed to make the audience lean in, a song that opens with to a simple acoustic guitar riff and Orzabal’s vocal. The arrangement could not be any more spare. Then it builds, and it builds, and having drawn us in, it then takes us into the sort of 360º production that has made Tears For Fears one of pop-rock’s great world builders. This is why it opens The Tipping Point, and why Orzabal and Smith chose to have it open their set.

“It’s incredibly unfamiliar for Tears For Fears. It’s like ‘What, have they gone country? What’s going on?’ Of course, it then develops into something else,” says Smith. “It’s like that little earworm, and it really does emotionally draw an audience in. One person standing onstage, starting the set, singing, and then the band slowly coming on, it creates a wonderful opening.

“The other way of doing it is to come in with a huge bang, which we’ve done before. There are different ways of doing things emotionally. You certainly do not want to come in with a whimper.”

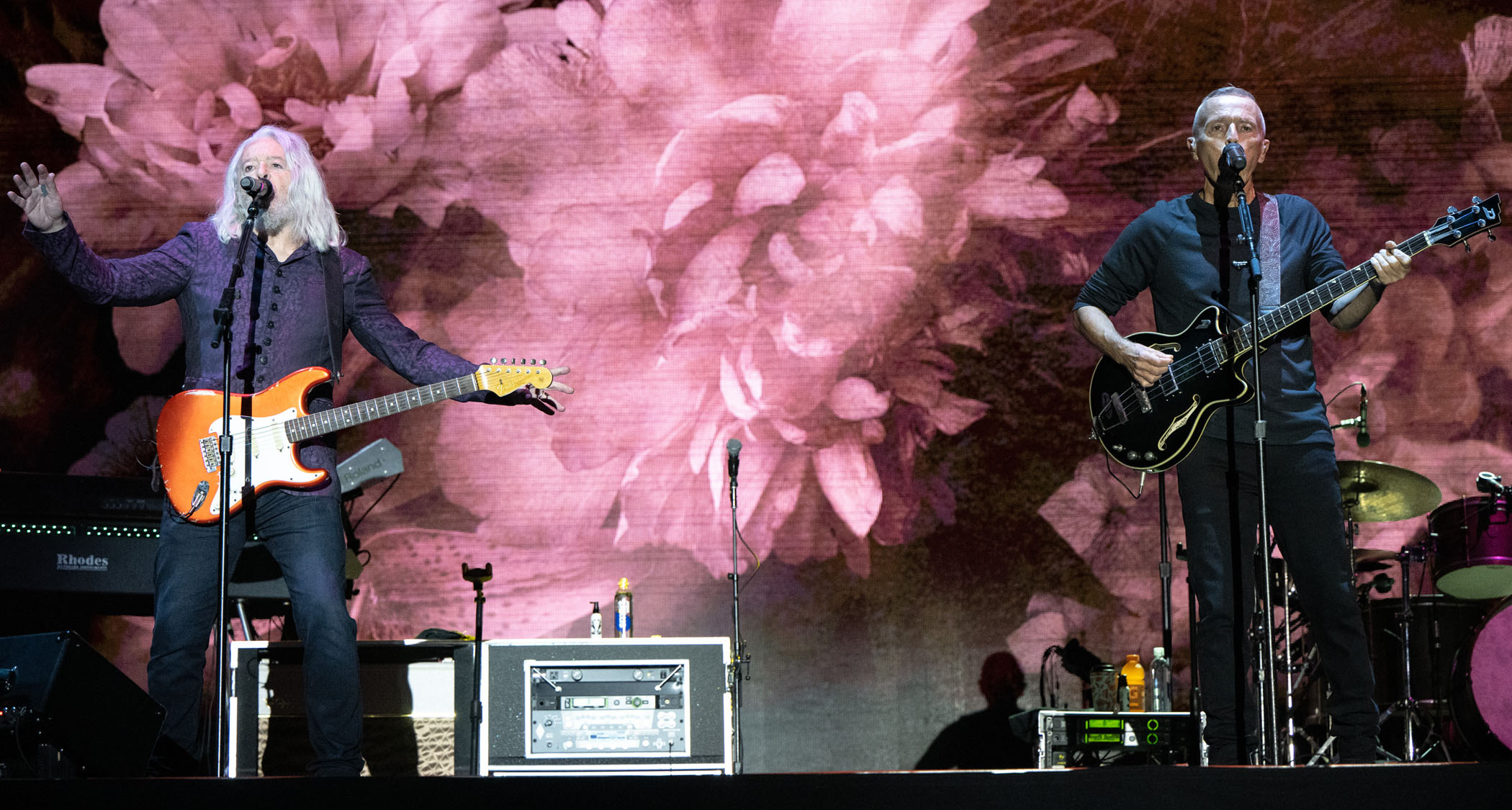

That set has been captured for posterity on Tears For Fears’ new live album, Songs For A Nervous Planet, which is out today (25 October) and features their July 2023 performance at the FirstBank Amphitheater, Franklin, Tennessee, plus four new studio tracks: Say Goodbye To Mum And Dad, The Girl That I Call Home, Emily Said, and Astronaut.

It is also being released as a theatrical feature, Tears For Fears Live (A Tipping Point Film), which is out in cinemas worldwide.

We can have a battle about the bass playing but eventually we will get it because we don’t care, ultimately, who does what. We just care about what comes out the speakers

Roland Orzabal

Orzabal wanted to shoot the film at the Hollywood Bowl. That is what were the Beatles recorded and he loved that album as a kid. But, all things considered, Franklin is a spectacular setting, with the rock illuminated by stage lighting.

And Franklin, onstage, is where we’ll begin our conversation in which Smith and Orzabal as they discuss the importance of creative independence, what they are looking for out of their production process – and from their collaborators – and why it is true that Orzabal really did open his wallet for Joe Strummer after the Clash frontman accused him of ripping him off. It's a mad world, indeed.

Some artists say that an album doesn’t feel real until it has been released and performed in front of an audience. How did performing The Tipping Point live change your perspective on it?

Curt Smith: “The thing we felt was that the new material really stood up to the old material. We were so incredibly happy with The Tipping Point as an album. But it also enabled us to enjoy [the show] more. Before The Tipping Point came out, we were getting a little bored with playing the same songs. This made our songbook much bigger, and really updated the story.

“With this tour, we’d started to make these visuals for the tracks that didn’t involve us being in them, and realising that that would work wonderfully as a backdrop because they’re telling their own story. The whole thing with The Tipping Point became more of a show than just going to see a band playing live. There were there were more elements to the show than just us.”

Did you feel a little bit like underrated as a live act? Because you have always had emphasis on performance.

Smith: “Yeah, I think we have, but the people that hadn’t seen us played really don’t know that. The people who haven’t seen us play live before – and we don’t play live all all the time, so that’s a big percentage of the people that listen to our music who have not seen us play live – don’t realise that we’re actually very much a live band.

The people who haven’t seen us play live before don’t realise that we’re actually very much a live band. They see two people and they think it’s couple of guys with synths and a backing tape and singing – and that is so not what we are

Curt Smith

“They see two people and they think it’s couple of guys with synths and a backing tape and singing – and that is so not what we are. For one, we’re both guitar players. Roland is a guitar player. I am a bass player. And our band is incredibly good. The people we play with now are really good.

“The great thing about the film is that it allows people that haven’t been to see us live go watch and realise that, ‘Oh, they’re actually musician musicians. They’re not just people who go into the studio and record.’ It really is more. Especially when you get to tracks like Badman’s Song, which is like an eight-and-a-half minute jam, which is wonderful to play live. I mean, it’s great fun for us.”

You doing this concert film made us wonder whether you might remaster that Massey Hall performance from 1985 and put it out on Blu-ray. A young Curt Smith in a yellow Ivy League shirt and a headless Steinberger. Brilliant.

Smith: “We are definitely vastly improved since then. Even though it wasn’t a bad show, but here’s the difference; most of Massey Hall we rerecorded but 99 per cent of what you hear on the The Tipping Point, on this film, is from the show. That’s it. There were a couple of boo-boos that we had to correct but apart from that is is all live performance.”

One thing that you do so well is you’ll write a hook that is so easily digestible, a totally elemental melody, then you pair it with a big idea, on that could be taught in a postgraduate programme, and then you make them work together.

Orzabal: “That’s a very good way of putting it. I don’t think we can get that any better.”

Smith: “I mean, we definitely took No Small Thing to its limits. It was very short to start with and we elongated it. We then got to the point where we thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we just kept on adding and adding and adding?’

“There was no way for us to put more on that song at the end without you missing everything, it just becoming noise. Those things, they are just interesting things for us to do. They are the exercises in production and recording that we enjoy.”

And you clearly enjoy that act of subverting straightforward pop compositions. Or you’ll tease a motif and use it elsewhere, like with Broken and Head Over Heels. What is the relationship between those two tracks and why did you decide to almost conjoin them as a DJ might mix them?

Orzabal: “Well, if I remember rightly, it was the musical theme, the intro of Head Over Heels [hums the piano intro] that was the linking object. There were a lot of discordant songs at the time in pop music, in the early ‘80s, and Broken, which was just going to be A dumb B-side was one of them.

“Within that rather discordant song we introduced the notion of the Head Over Heels motif, such that when we went into rehearsal for the In My Mind’s Eye video and tour [1983] we just put the two together and they seemed to work. Then it was from hearing that live that we decided to put the live version of Broken on the Big Chair album at the end.”

That feels like such a bold move to have one track foreshadowing the next like that on the record.

Orzabal: “It’s almost prog rock.”

Smith: “Yeah, it’s that juxtaposition that works. You’ve come out of this furious and bombastic love song into an incredibly discordant, less than a minute’s worth of mayhem, just when you thought you were safe! [Laughs] These kinds of things interest us.”

There’s more than meets the eye to Everybody Wants To Rule The World, too. You could say it is in D major, in 12/8, and on sheet music it looks simple. But the sound is so three-dimensional. It’s like you when you have something that’s simple, it has to be something more.

Orzabal: “Does it have to be something more? Yeah! I think that we are both easily bored, and I have been in musical situations – and recording sessions – where I am actually quite shocked by how simple the thing is that we are listening to over and over and over again. I am just gobsmacked! And I think Curt and I are similar, like, ‘Okay, we did that. Let’s try something else now. Let’s put a little bit more on the top of it.’ That’s all it is. It’s partly boredom.

The records that I like to listen to, some are simple and they have their own value, but the ones that interest me the most are the ones I have to listen to a bunch of times to try and work out what’s going on

Curt Smith

Smith: “Well it’s partly boredom but it’s also taste. The records that I like to listen to, some are simple and they have their own value, but the ones that interest me the most are the ones I have to listen to a bunch of times to try and work out what’s going on. I remember sitting with headphones on and listening to Peter Gabriel’s third album and trying to work out what he was using, and what sounds were there. As opposed to just listening to it as just a recording.

“I wanted to know the bits. I think that there’s a certain joy in it. There’s a certain joy in putting together puzzles where all these pieces suddenly fit and become this one piece of magic. I think Everybody… does that very well because there are not that many bits in it but they fit together and fire off each other so well. There’s a magic about it, and a lot of it – to be blatantly honest – is trial and error.”

When you get that puzzle right, that’s what makes it last and stay fresh. The elements might be simple but as a whole, it’s something different. It’s a bit like how a painting might reveal different things each time you look at it.

Smith: “I think that if you make anything of quality and depth it lasts, personally. Even if you go back to the Beatles, and you are looking at a different technology back then. You are just fascinated by how they could do that with the technology available at the time. That’s you as a producer. That’s you trying to really wrap your head around how that is possible.”

Joe Strummer said to me, ‘Hey Roland! You owe me a fiver. Because on Sandinista! I sang everybody wants to rule the world’

Roland, did you really give Joe Strummer £5 because you ripped off The Clash on Everybody Wants To Rule The World?

Orzabal: “He said to me, and this was a long time ago, ‘Hey Roland! You owe me a fiver. Because on Sandinista! I sang everybody wants to rule the world.’ So, to be honest with you, I didn’t have a fiver. I had a tenner.”

Smith: “I knew that was coming! [Laughs]”

Orzabal: “I signed the tenner.”

Smith: “And said, ‘Now I’ve signed it, that makes it a fiver.’”

Orzabal: “So there you go. Yeah.”

What was the biggest thing you learned in terms of production from doing The Tipping Point? It’s a constant learning process.

Orzabal: “First of all we learned, Curt and I, together with Charlton Pettus, our guitarist and producer, that we could make the record on our own, and we also learned that we could take what other people had done and work it into the fabric of the album. We were just full of confidence.

One of the big lessons, which really I think we knew at heart anyway, is that there’s no one better to produce our music than us

Curt Smith

“We had done it before, of course. We had spent four or five years making Seeds Of Love but this was at a period when we were just brimming with confidence. We have different ways of listening to things. I think we were listening to it quite loud in Charlton’s room, but Curt would take things away, I would take things away.

“Curt would have gripes about certain things that I wouldn’t really worry about, and vice versa. And so I think what we learned – and without any pain involved – we would take things away, we would come back in the morning and we would have a very, very clear idea of what we needed to do.

Smith: “I also think one of the big lessons, which really I think we knew at heart anyway, is that there’s no one better to produce our music than us.

“For us, as producers, I think that what our previous manager didn’t realise was that we are by far the best people to produce our music. If someone else involved then it is not ours. I don’t think he gave us enough credit to actually believe in us that much, and that was quite sad.”

Neil Taylor was a genius guitarist. Neil is a genius guitarist, still is. He can do things that we can’t do – and no one I know can do the things that he does

Roland Orzabal

Charlton is such an important part of your band, as a producer, as the guitar player. Do you have a similar relationship with him as you did with Neil Taylor, and how do they compare as players?

Orzabal: “Neil was a genius guitarist. Neil is a genius guitarist, still is. He goes on YouTube every now and again and you can watch him play his solos from Tears For Fears and other things. He is a remarkable guitarist. There is no doubt about it. He can do things that we can’t do – and no one I know can do the things that he does.

“What it is with Charlton is that he is a multi-instrumentalist, and he understands the language of music, and nothing you can do is going to completely pull the wool over his eyes. Sometimes when you bring in stuff that’s programmed, a song with sounds that he doesn’t know, he isn’t aware of, he will be impressed for about five minutes until he takes it all apart.

“He speaks Curt’s language and he speaks my language. He is an archetypal modulator, or translator, and his brain is incredibly open to everything.

Smith: “I think understanding both of us is the key to it, and you can talk to him in various different languages. Like, you can talk to him technically, or you can talk to him emotionally. ‘It’s not moving. It’s not got enough darkness.’ Or whatever. He’ll get that, and he will know what you mean by that. So it’s a different relationship. If there was anyone, he’s the best we’ve worked with.

“He’s definitely not like Neil. Maybe in our early days he’s a bit more like Ian Stanley but even then, looking back at Ian’s time, I think we were more producers than Ian was. So maybe Chris Hughes [is like Pettus]. Chris Hughes got us both to that degree but he wasn’t as musically adept as Charlton is.”

Our previous manager didn’t realise was that we are by far the best people to produce our music. If it is someone else involved then it is not ours. I don’t think he gave us enough credit to actually believe in us that much, and that was quite sad

Curt Smith

It must be a little difficult for outside parties, for session players – or producers, as you’ve said – to offer suggestions, or ideas.

Smith: “Charlton is not shy about giving us suggestions that are unwelcome.”

Orzabal: “But unlike people we have worked with before, he will show by example. So for instance, we were playing around with Emily Said, in a way that it wasn’t quite right. The song wasn’t actually finished, and Curt and I had a bit of a disagreement about things, and Charlton said, ‘All right...’

“The next morning, lo and behold, he’s put all these acoustic guitars, he’s got this crazy drum fill, and I go, ‘Well? Hmm… Maybe!’ He’s more like that. He’s hands-on. So we have a lot between the three of us. We can have a battle about the bass playing but eventually we will get it because we don’t care, ultimately, who does what. We just care about what comes out the speakers.”

Is this sense of play and discovery something that keeps you going? That feeling that there is more to learn.

Smith: “We’ve never go to the stage where we’ve thought we have made the perfect record. We are always on the lookout to discover new ways of doing things, new sounds, what else can we do to make this interesting.

“As Roland mentioned earlier, we get bored very easily, so doing the same thing over and over again does not interest us in any shape or fashion. Until we have something new and interesting – be that musically or lyrically – until we have something to say then we say nothing.

“I think that sense of boredom and wonderment at what music can do still exists for both of us, and as long as it does we will continue to try and plumb those depths of what is possible.”

In terms of sounds, one of the big ones for Tears For Fears was the sample of Led Zeppelin’s snare sound. But is that era for production over, where you can find a readymade sound? Or will it always exist?

Orzabal: “Both statements are true. We have moved on but we still have readymades. Nowadays, I would say every musician has pretty much the same thing on their computers, and if you keep your ear out and you know how to use them you literally can press ‘play’ and get these remarkable results. You just have to look for it.

Smith: “A lot of it is down to how you utilise it. You can use a standard sound in a new way, or on a song where you wouldn’t think that standard sound would work in, so it’s completely down to how you utilise the sounds that are available to you. Some people do it incredibly well. Some people do it in a boring way. We try to make it interesting.”

Let’s finish on the most utilitarian note possible. Why Duesenberg bass guitars for you, Curt? And where did your walnut Stratocaster go, Roland?

Smith: “I am not the technical guy. I’m like, ‘That looks good. I’ll try it and see if it sounds good.’ So, the different ones I’ve used are for simple reasons – one is growlier than the other. Why? I don’t know, I leave that to the technical people. But it is, it gives me the growl that I want. And it is warm and it sits in the track nicely.

“It is a warm with a bit more bite, and Duesenberg were kind enough to design it for me, and make the one-off. Mine is literally a one-off guitar that they designed to replace the Hofner I had because they thought it could sound better than it did – and they were correct.”

Orzabal: “[Deadpan] I have 50 guitars. And I’ve got some beauties. I’ve got to say. I don’t buy fast cars. I used to buy fancy cameras, and I kind of still do, but my obsession is guitars. The walnut Strat, called ‘The Strat,’ that you referred to, is actually in storage in Britain, and will probably be coming over at some point.”

That’s good to hear. Because there was rumours that you had given it away – not that that’s an ignoble fate for the instrument but…

Orzabal: “I may have had more than one!”

A lot of our ideas, or at least the feel of an album, comes from being in the studio

Curt Smith

You have some big shows in Las Vegas coming up but after that might we see you in the studio sometime soon and do you have ideas for new material already?

Orzabal: “I do, yeah. But I’m keeping schtum. [Laughs]”

Smith: “Yeah, but until you get into the studio you don’t know what that is. I mean, to be honest, there were ideas for what the last album we made was going to be and they changed over the years. Shit happened over the years. Until you get to the actual point of making it you don’t really know. Things change and a lot of our ideas, or at least the feel of an album, comes from being in the studio.”

- Songs For A Nervous Planet is out now via Concord. Tears For Fears (A Tipping Point Film) is in cinemas now. See Tears For Fears for tickets and screening details.