From Kakadu and the Great Barrier Reef in the North, to the Snowy Mountains in the Southeast, and jarrah and marri forests in the Southwest, Australia is home to incredibly diverse ecosystems. Many of our plants, animals, birds and fish are found nowhere else in the world.

Our First Nations people protected these living wonders through their holistic approach to managing the land and caring for Country for more than 65,000 years. But the European settlers took a different approach and the land suffered.

Federal laws made in 1999 to better protect the environment are failing. Climate change is not explicitly mentioned in the legislation. These shortcomings have prompted a volunteer environment group to mount a legal challenge against federal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek “to protect our living wonders from coal and gas”. The matter is currently before the courts.

This week’s new report from the Climate Council Australia (which I was an expert reviewer on) explains the problem with our environment law and charts a way forward.

The fundamental flaw in our national environmental law must be urgently addressed if we are to have any hope of protecting our wildlife and habitat into the future.

Australia’s national environmental law

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) should be designed to keep our living wonders safe from harm.

The primary objective of the EPBC Act is to:

provide for the protection of the environment, especially those aspects of the environment that are matters of national environmental significance.

But it’s clear the environment is deteriorating. The EPBC Act requires a comprehensive assessment of Australia’s environment every five years. The latest assessment, published in 2022, found the state of Australia’s environment is poor and getting worse.

Climate change was identified in that assessment as one of the greatest threats to all aspects of the Australian natural environment. Climate change is a compounding factor that increases the impacts of other pressures on our environment, such as land clearing, invasive species, pollution and resource extraction.

However, climate change is not considered directly in the EPBC Act as one of the factors affecting matters of national environmental significance.

According to the Climate Council report, since 1999, 740 new projects to extract coal, oil and gas have been approved or passed, with 555 of them not having undergone detailed environmental assessment. Burning these fossil fuels increases greenhouse gas emissions and makes climate change worse.

In 2020, a scathing independent review of the EPBC Act led by former competition watchdog chair Graeme Samuel found the act is ineffective, outdated and needs comprehensive reform.

Climate risks to Australia

In 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released the most recent comprehensive global assessment of climate change risks.

The special fact sheet about climate impacts on natural and human systems in Australia and New Zealand provides a helpful summary of that assessment.

It lists nine key risks in Australia associated with climate change. Of these, the top five risks for our living wonders are:

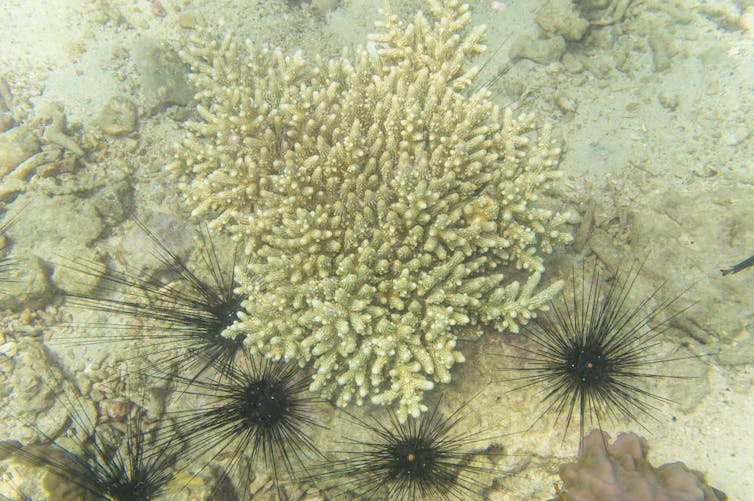

“loss and degradation of coral reefs and associated biodiversity and ecosystem service values [what they are worth] in Australia due to ocean warming and marine heatwaves

loss of alpine biodiversity in Australia due to less snow

loss of natural and human systems in low-lying coastal areas due to sea level rise

increase in heat-related mortality and morbidity for people and wildlife in Australia due to heatwaves

inability of institutions and governance systems to manage climate risk”.

That last one is particularly relevant to the EPBC Act.

A legal challenge is underway

To test the climate blindspot in the EPBC Act, the Environment Council of Central Queensland submitted 19 reconsideration requests to Plibersek in July 2022.

The minister was asked to reconsider the previous evaluation of 19 coal and fossil gas extraction projects under the former government, because they did not take into account potential harms on Australia’s living wonders.

The environment council provided the minister with thousands of state and federal government reports listing the impacts of climate change on several thousand matters of environmental significance.

In November 2022, the minister accepted 18 reconsideration requests as valid. However, in May 2023, the minister decided not to change the climate risk assessments by the previous government for three of the projects she was asked to reconsider. In Plibersek’s official responses she determined that based on the new information provided to her in the reconsideration requests, it wasn’t possible to say the proposals would be a “substantial cause of the stated physical effects of climate change” on a matter of national environmental significance.

The matter is now in the Federal Court. Last week, the environment council challenged Plibersek’s rejection to reconsider two of the three coal mine expansion projects, both in New South Wales. A decision from the judge on this case is pending and should be provided in the next few months. A spokesperson for the minister has advised the media they would not comment “as this is a legal matter”.

Protecting our living wonders means fixing Australia’s environment law

We need to fix Australia’s national environment law, making sure it contains an explicit objective to prevent actions that accelerate climate change. We need a national environment law that genuinely protects our environment by stopping highly polluting projects and enabling ones that can help us rapidly switch to a clean economy instead.

Every fraction of a degree of avoided warming matters for preserving our environment. Every decision made under our national environment law can either help or hinder the urgent task to drive down greenhouse gas emissions.

David Karoly is a Councillor on the Climate Council Australia. He provided an expert report in support of the initial reconsideration request made by the Environment Council of Central Queensland to the Minister for the Environment. David is also a Member of the Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.