Jason & The Scorchers are one of the great shit-kicking, country-fried rock’n’roll bands.. But how did these cult heroes never become huge? In 2008, cowboy-hatted singer, guitarist and lunatic showman Jason Ringenberg told Classic Rock about the highs, lows and screw-ups of a career like no other.

Farmer Jason Ringenberg is sitting in his barn, 20 miles south of Nashville, Tennessee, and he’s enjoying the view. Surrounded by a bunch of kids, a dozen chickens, a pony, a pig called Petunia and a goat named Azalea – “Goddamn, she ain’t worth but a dang” – Jason is breathing fresh air. He’s organic. He drives a “little beat-up Mazda” and, right now, he is as far from rock’n’roll madness as it is possible to be.

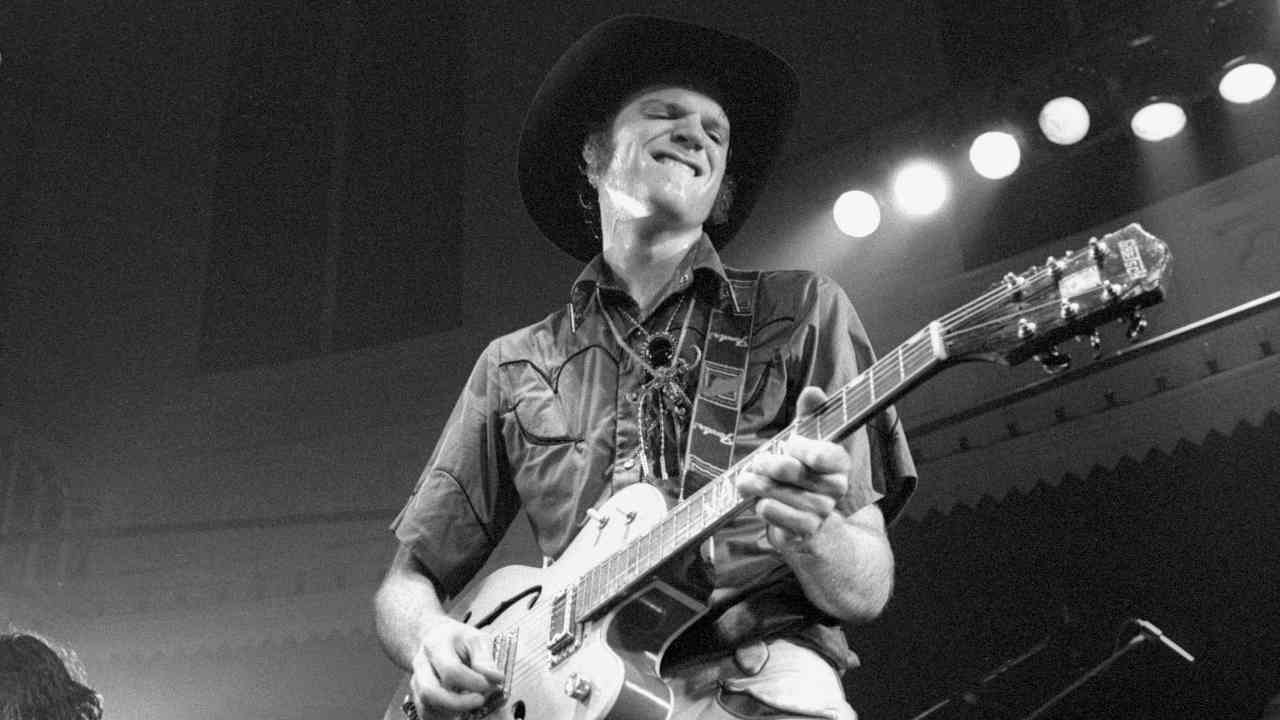

In a few weeks time Ringenberg will quit this rural idyll and go earn a living as frontman for one of the most vital kick-ass southern gentry groups ever to walk the planet: Jason & The Scorchers are back. Which means he’ll be swapping his dungarees for that ol’ black stetson and them trashy rhinestones, hoping to revive the era in which his band were considered to be the avatars of new country rock.

It’s a time to take stock, and Jason is philosophical as he teams up again with his old sparring partner, ace guitarist Warner Hodges, and renews his acquaintance with the back catalogue that made the Scorchers, undid them and nearly broke them – as men, friends and musicians.

Jason & The Scorchers were big news when they emerged in the early 1980s. Before the Paisley Underground, and long before alt.country and Americana (fairly pointless terms all) Jason & The Scorchers were going to be a cross between the next Led Zeppelin, according to the folks at Capitol Records, and a punk riposte to Lynyrd Skynyrd. A fervid English press lapped up their debut EP, featuring a barnstorming take on Bob Dylan’s Absolutely Sweet Marie, and the brace of albums that followed it: Fervor, and the classic Lost & Found in 1985.

Described by the NME at the time as “the greatest rock showmen of 1985”, the band had the chops and the chutzpah to make all the above happen. Two years later, by 1987 they were wounded animals ready for slaughter; too rock for country, too country for rock’n’roll.

Now, on the eve of a third attempt at regaining their initial mantle as world beaters, Jason remembers where it all went so wrong: “We peaked too early. Our European audiences were so explosive we believed our own hype. The shows were special, the potential was just immense. We put heart and soul into Lost & Found and nothing happened. We were left standing on shaky ground, making less than $100 a week. We were pitiful. The album that should have made us in America was [1986’s] Still Standing and it wasn’t any good. Why? Bad commercial decisions, mainly, and far too much drink and drug excess.”

For a Mennonite Amish boy raised in the Prairie State of Sheffield, Southern Illinois, Ringenberg’s chosen calling as a wild-eyed rock’n’roll frontman was always going to raise eyebrows. His own purist view for the Scorchers was compromised once Hodges, drummer Perry Baggs and bassist Jeff Johnson rebelled against him.

“I took my eye off the ball, but there was way too much alcohol and cocaine around. We started believing in that southern mystique thing. We moved to LA and became a California band. We hired the heavy metal producer Tom Werman, who was great for Mötley Crüe, but we lost our – my – Nashville roots.

“I never did drugs myself, or even drank a lot, because I couldn’t part with $1,000 to get high like the other guys would, so there were constant tensions. I was like this rock’n’roll country hillbilly, and they were rapidly getting into hard rock. Etcetera. The combination was brilliant when it worked but, hell, when it didn’t… It got the point where I’d tell the road manager, ‘Once we’re off stage, give me a hotel room as far away from the others as possible’.”

Anyone who ever saw Jason in his mid-80s pomp, one of the most hepped up show-business characters ever, might find this hard to swallow. He agrees that the dichotomy is implausible. “I was 100 per cent testosterone-fuelled – my hero is Jerry Lee Lewis – but my stage act is all bravado; I am mentally crazy as anyone, but afterwards I’m a serious guy. I believe in professionalism. Even during our vintage years there wasn’t a single night – and I can honestly say this – when someone in the band wasn’t completely plastered after a gig. Someone? Hell, maybe all of them. I can’t spin it wrong. They had a code when we played – they weren’t too high then. But afterwards… I didn’t want to be anywhere near ’em.”

Jason had set out on July 4, 1981 to realise his dream. The remaining Scorchers made it happen. They were a democracy of sorts, although their three against his one meant they had a stronger personality. Before Lost & Found Jason predominated. After 1985 his vision of a rock group that mutated the Ramones and the Stooges into George Jones and Merle Haggard ceased to exist.

University educated, well read, and boasting musical tastes that veer from David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs to Tom T Hall’s Who’s Gonna Feed Them Hogs, Jason Ringenberg is a real post-Elvis-era piece of work. A social-liberal by American standards, he was delighted to have his band support REM when they were driving the same road to stardom, and Bob Dylan when the Scorchers were at their peak.

“When we were a forgotten band REM always name-checked us, and when we toured with them they were fellow pioneers. They were a step ahead of us but they helped us out. They’d be making 300 bucks to our 100, driving a newer van, getting better press, yet after gigs they often gave us the money for a Motel 6. Regular guys. Same with Dylan. I’d bump into him on the catering line and he’d say: ‘Man, the barbecue is sure good tonight’. We’d talk about drummers and tour-bus experiences but I was honour bound not to talk about his songs. I heard we got that support cos he liked our version of Absolutely Sweet Marie.”

Warner Hodges lives in the Brentwood suburb of Nashville in a 4,000-square-foot homestead with his family and three North American yard dogs. Warner is yang to Jason’s yin. Where Jason is a socialist by nature, and a man whose Empire Builders solo album and songs like Rebel Flag In Germany have brought him plenty of death threats by email, good ol’ Warner is a military brat whose father was a country musician who toured with Johnny Cash and did two tours of Vietnam. Warner himself is just about to play for the troops at Guantanamo Bay “to show those folks that we still care. Even though I disagree with the war in Iraq.”

Warner has plenty of heart. It was he who instigated a 2007 reunion benefit for original Scorchers drummer Perry Baggs, sadly suffering from acute diabetes and kidney failure [sadly, Biggs died in 2012].

“We were a shambles but we paid some medical bills,” he says. “We do have a good body of work and I’m happy to get back together with Jason again. I kind of owe him because I used to think I had the tough job in this band, whereas he takes most of the pressure.”

Although he hasn’t signed the pledge, Warner sobered up in 1982. “What made us wild and good also made us combustible,” he reckons. “Jeff Johnson quit cos of his extra-curricular activities, and for years we couldn’t play without being alcohol-fuelled. One day I realised the drink was winning and I was losing. I needed to get my life back – or face poverty and death.”

After Jason & The Scorchers imploded in 1989 following the feeble Thunder And Fire album, Warner moved to New York where he did numerous sessions, played with Eric Ambel’s Roscoe’s Gang and, notoriously, joined Iggy Pop’s road group, prior to the singer’s Brick By Brick album.

“I used to roll down the road listening to the Stooges, so working with Ig was a blast,” he recalls. “But he fired me for showing my ass on stage and being generally drunk. That cost me a job. I’ve always been attracted by magnetic characters and he is plenty of those. He hired me after I turned up at his Manhattan loft above a fire station and we wrote a bunch of shit together, him bouncing off the walls like he was in Madison Square Garden.”

That version of Iguanaville also included former Hanoi Rocks madman Andy McCoy and Psychedelic Furs drummer Phil Calvert – quite a wild bunch by all accounts. Warner was on a one-way ticket to Palookaville if he hung around. “So Ig kinda did me a favour when he fired me.”

In their third incarnation, in the mid-90s Jason & The Scorchers released the excellent albums A Blazing Grace and Clear Impetuous Morning, but the will was fading. Now, the band’s mainmen believe they are older, wiser and better. Jason insists that “Warner is playing out of his skin again”, while Hodges says that “Jason is certifiably loony as hell on stage, but turn his light switch off and you wouldn’t even know he was in the room. We’re good friends again.”

There are many reasons why Jason & The Scorchers are ripe for re-examination. Without them it’s doubtful whether the rebirth of southern rock would be possible. And life without Kings Of Leon, Legendary Shack Shakers and Woodbox Gang wouldn’t be great. The short version is this: Jason & The Scorchers were a great band in their heyday and the Nashville scene needs that blueprint today.

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 119