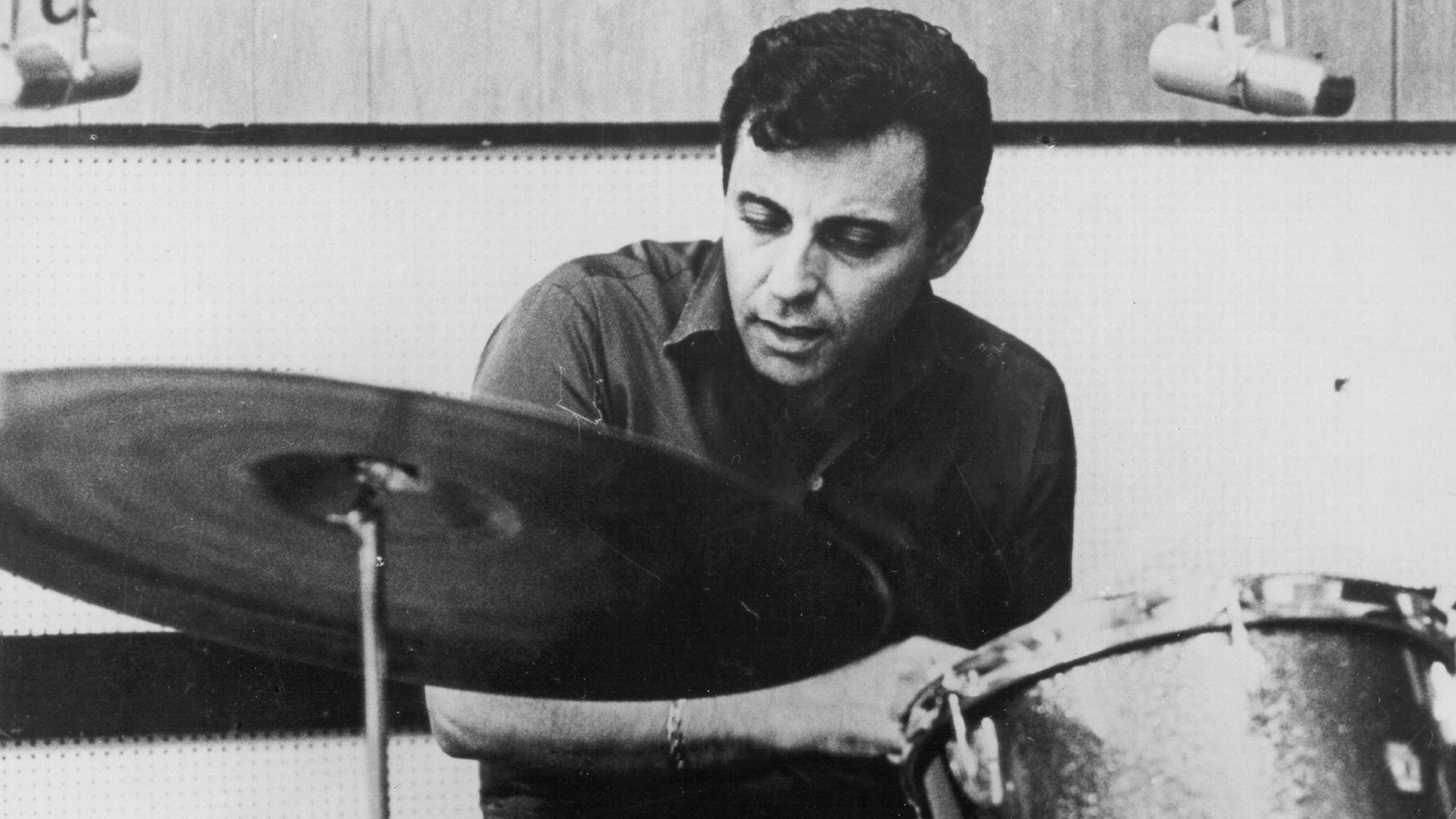

The knowledge and stories that Wrecking Crew legend Hal Blaine accumulated during his storied session career could fill volumes.

He played on six consecutive Grammy award-winning Record of the Year performances from 1966 through to 1971, as a key member of The Wrecking Crew (the name coined by Blaine for a group of successful session musicians in LA in the 1960s). If a song was in the Top 10 during the ’60s all the way through to the early-’80s, the drummer was more than likely Blaine.

The Wrecking Crew's Hal Blaine: my 11 greatest recordings of all time

Of those hyper-productive years in The Wrecking Crew, Blaine recalled "magical times. You’ll never get music like that again, and you won’t get a group of musicians like The Wrecking Crew together again. The business just doesn’t work that way anymore.

You’ll never get music like that again, and you won’t get a group of musicians like The Wrecking Crew together again

“Funny thing is, we had no idea that what we were doing was groundbreaking or revolutionary. Doing a TV show in the morning, a Beach Boys track or a Phil Spector session in the afternoon, then working with Frank Sinatra or Simon & Garfunkel after that – that was normal to us.

"We were working musicians, playing great music. We got the job done, and we made a hell of a lot of money doing it."

So it's no surprise that Blaine is one of the most influential drummers of all time, but even if for some of his biggest fans, his identity was something of a mystery. Take Rush legend Neil Peart. "When I was growing up," Peart once told MusicRadar, "I played along to the radio, so I played along to Simon & Garfunkel, The Beach Boys, The Association and The Byrds, and I was really playing along to Hal Blaine."

"There was another drummer who said that he was shattered to find out that his six favorite drummers were all Hal Blaine!"

Peart actually reached out to Blaine when he published his beautifully reflective autobiography, Ghost Rider. Speaking to Modern Drummer in 2005, Blaine revealed, "I got a very nice letter and an autographed copy of Neil Peart’s book, Ghost Rider.

"He’s a beautiful writer. In his letter he said the same thing you just said. He said he knew every one of those records and that he learned from the records that I played on."

"The drummer with The Knack, Bruce Gary, was once asked who his favorite drummer was, and he said he was never so disappointed in his life to find out that a dozen of his favorite drummers were me."

So what he said, counts. This classic interview, first published in MusicRadar's sister magazine Rhythm, contains a few priceless pearls of drumming wisdom, as well as real insight into the development of Blaine's playing and career.

What advice would you give studio session drummers?

“If you’re going to work in the studios, it’s really not different from working any other job. If you work in a department store, you want to be pleasant to your customers, especially if you are being paid a commission. The nicer you are to your customers, the more they might buy from you. They appreciate nice.

I have a motto: ‘If you smile, you stick around a while, if you pout, you’re out!’

Hal Blaine

"I have a motto that I’ve used for years, and that is, ‘If you smile, you stick around a while, if you pout, you’re out!’ I’ve gone through guys that consider themselves ‘best of the best’ and you can’t talk to them! You can’t say, ‘We’ve got a five-minute break, please be back here in five minutes.’ They would look at you like, ‘I’ll be back here when I want to be back here.’

"Well, naturally, you would never call them for a session again. In a short time, they would go through many producers who decide, ‘We don’t need this guy on our session, he’s dragging us down. When you talk about talent and chops, one of the things you learn early in the studios is that ‘less is more’. One good shot in the right place in a song is worth a million paradiddles.”

Has working with artists like The Beach Boys, and Elvis elevated your level of playing?

“Absolutely! It gives you confidence! Often times you would do a session, I don’t know about today’s sessions, but in those days sometimes a producer would say, ‘Look, on the intro I’d like you to get that feeling of The Beatles for the first eight bars, and then maybe we could go into an Animals thing on the second eight bars, and then a certain bridge like another group.’

"I would say, ‘Look, that’s all well and wonderful and I’ll do whatever you want, that’s what you hire me for, but wouldn’t you rather make a record that the other groups would say, ‘Hey, let’s make a record like that?’

"Make your own record that you’re proud of. You don’t need a Beatles beginning and a something else, which starts to sound like it’s put together by committee. So, they would say, ‘You’re absolutely right, I should have thought of that!’ I don’t think there ever was a producer who said, ‘No, I want to do it this way.’

"Because there’s a certain respect that precedes you when you go in the studio when you’ve had all these hits, I must know what I’m talking about! It’s kinda nice and I don’t mean that in an egotistical way.

"Guys appreciate that in the long run. Especially if they get a gold or platinum record!”

Have you ever made a ‘beautiful mistake’, like an accident that became a key part of the song?

When you’re a professional and you’ve done it as long as I have, you learn that when you make a mistake, if you do it every eight bars, it’s not a mistake!

“When you’re a professional and you’ve done it as long as I have, you learn that when you make a mistake, if you do it every eight bars, it’s not a mistake! The perfect example of that is Phil Spector’s hit, ‘Be My Baby’ [released in 1963, it reached Number Two on the US Billboard Pop Singles Chart and Number Four on the UK’s Record Retailer] which starts out ‘boom, boom-boom, bang – boom, boom-boom, bang’ [a ‘1, &-3, 4’ pulse].

"Now, who knows or not if that was actually ‘written’. We may have been rehearsing it as a ‘boom, bop, boom-boom, bop’ [‘1, 2 & 3, 4’], and then we got into recording the thing and it was, ‘Start it Hal!’ and I went ‘boom!’ and I missed the snare on the second beat but I got it on the fourth beat. So I did it every bar!

"I made the adjustment in a nano-second and before you know it, the song is based on that. That was around 1961. Around 1964/65, I go in and do a record with Frank Sinatra, ‘Strangers In The Night’. Guess what the beat was that I played to it? ‘Boom, boom-boom, bop’. It was a Number One record as well as a Grammy award winner! But it was the same beat.

“Another perfect example was not exactly a mistake, it was on my first Grammy Award-winning Record of the Year, ‘A Taste Of Honey’ with Herb Albert and the Tijuana Brass in 1966. The beginning of that song started with an obligato horn piece and then ‘boom!’ It started."

"Nobody was coming in right, the horns were a train wreck every time! So, about the third or fourth take I’m sitting there in the middle of the room with all the guys and they played the intro and I looked at ’em and I went ‘boom, boom, boom, boom’ [mimics triplet roll intro], and everybody came in.

"That became the hook of the tune. That was the whole song. Just my comedy mind saying, ‘You’re going to come in right this time guys!’ How can you miss?”

Did you have any special tricks that you used to get a great drum sound?

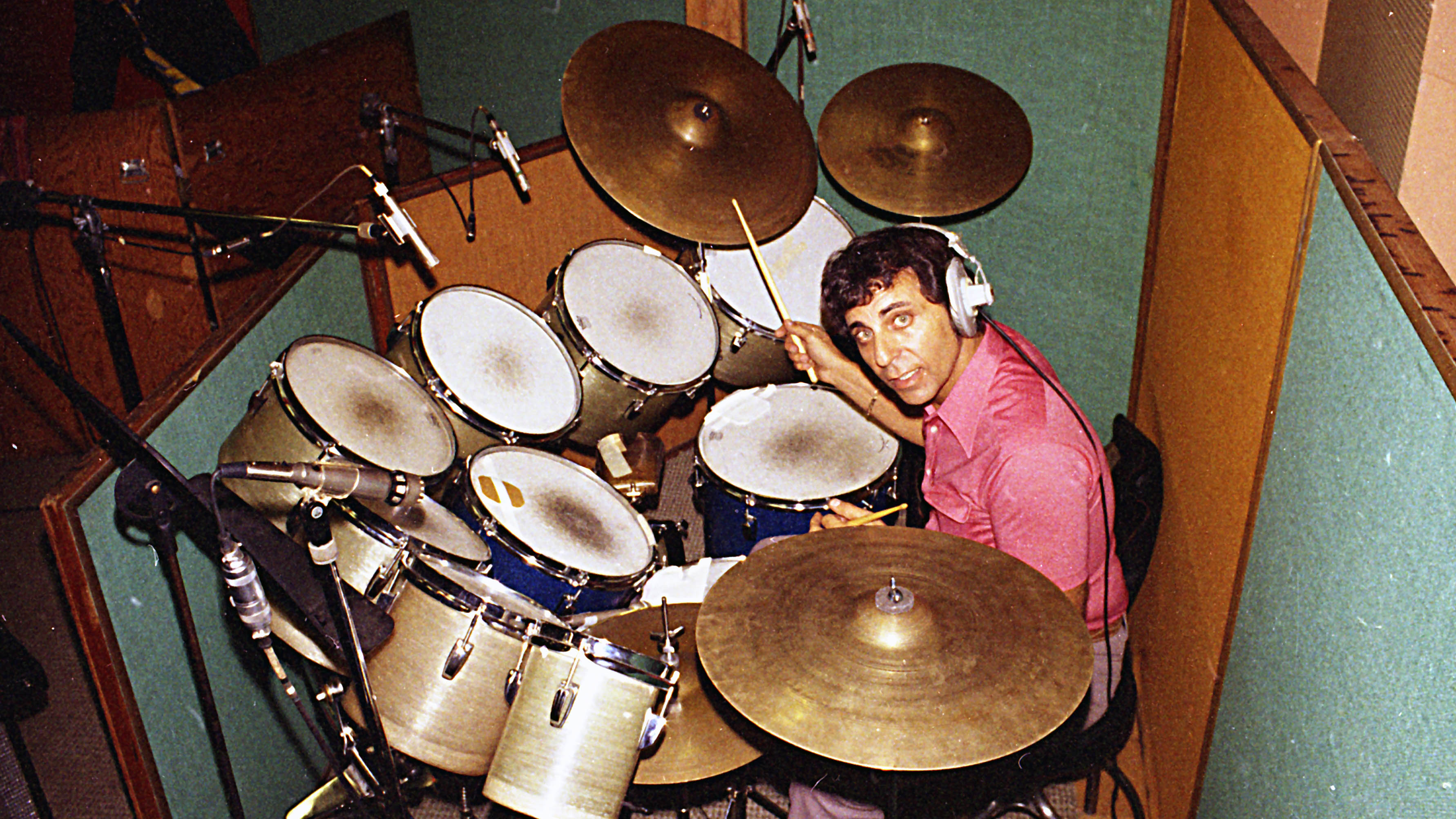

“I know people talk about the wallet on the snare trick but I always had a hankie in my pocket that I taped on the snare just to get rid of the overtone so that it was a flat, dry hit. It always worked for me. Toms were usually wide open.

"There was a time when Rick Faucher, my drum tech, came up with a great idea, especially with the ‘Monsters’ [custom-made fibreglass concert toms from 6" to 16" that were mounted on rolling stands].

"He had a seamstress that made what we called ‘shower caps’. Regular bed sheet material the size of each drum and they had an elastic ring in them. They stretched over the head to muffle it and they recorded amazing!”

Did you have a favourite kit to record with?

“Well, the one I used most and I guess you could call my favourite, was the four-piece Ludwig Blue Sparkle kit [this was a 1962 three-ply maple kit with 22" bass drum, 13" small tom, 16" floor tom and Supra-phonic 400 snare].

"I had two identical kits – the other kit was a 1965 – so I could always have one set up. It seemed like every drummer in town that ever wanted to play rock’n’roll, suddenly they all bought Ludwig Blue Sparkle four- or five-piece sets! Herb Alpert used to follow me around the studios a lot of times at A&M and I’d see him looking in the window or the door and we’d take a five-minute break and he’d come back and be looking at my drums and asking, ‘What kind of drum is that? How do you get that sound?’

"I’d say, ‘Herb, it’s just a bass drum! I do it with my foot! You saw me do it a million times!’ He had a lot of problems after he had to get a road band and go out and do concerts. He couldn’t get that bass drum sound that he wanted.”

How involved were you with engineers/artists as far as the drum sound goes?

“The engineers usually came in and did the mics. In those days, it was usually two overheads, one between the snare and the hi-hat, one on the bass drum and one on the floor tom. That was it.

"I remember recording with Simon and Garfunkel in New York. Their engineer/producer Roy Halee used to tell you to play. He’d walk around always listening to you just jamming. He would point, and that’s where he wanted a mic. It was all in what you hear.”

What do you think about the current state of the music industry?

“Well, all the technology is fine if you know how to use it. I think it’s very difficult to somehow get the right ‘feel’. All I know is we used to go for ‘feel’ as opposed to robotic performance. When we used to do records, if it felt good, you had a good record.”

• More Wrecking Crew: Carol Kaye - the Queen of Bass